Aromas rich with fruity and earthy tones fill the air each time Amy Vachon goes to work creating a batch of craft chocolate from beans she acquires from Africa, Central America, and the Caribbean.

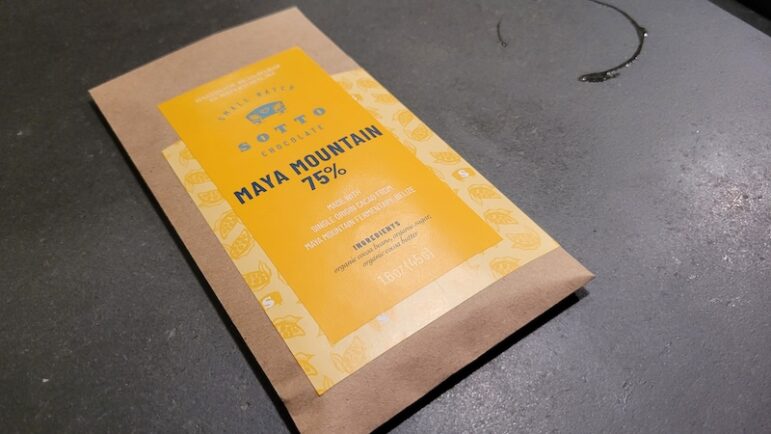

The Watertown resident began making her own chocolate in 2017, and Sotto Chocolate was officially registered as a business in 2020. She has converted a corner of her home near Watertown Square into a chocolate workshop.

Regulars of the Watertown Farmers Market will recognize Sotto Chocolate. Vachon can be seen at the table, often with her husband, Marc, selling the bars of artisanal chocolate which she creates from bean to bar.

The name, Sotto, comes from an Italian word used in music that means an undertone, said Vachon, who also plays the violin.

Vachon has always enjoyed creating things, and for a time tried her hand at cheesemaking. She could make a couple types of cheese, but found that it was not a pursuit that would work well in her home.

Then, one Christmas, Marc got her craft chocolate subscription.

“It’s this really cute subscription service, and in the little box, there were three or four bars from a single craft chocolate maker in the United States, and a little story about this person and how they decided to make chocolate,” Vachon said. “And many of them were people who were making it in their homes and who were passionate about chocolate.”

She discovered how the flavors of the chocolates differed with cocoa beans from one place producing a raisiny taste, while beans from another region make a bright, fruity chocolate.

“It was just fascinating to taste this all for the first time, really consciously. And then I just started learning more about chocolate and taking a couple of tours of places,” Vachon said.

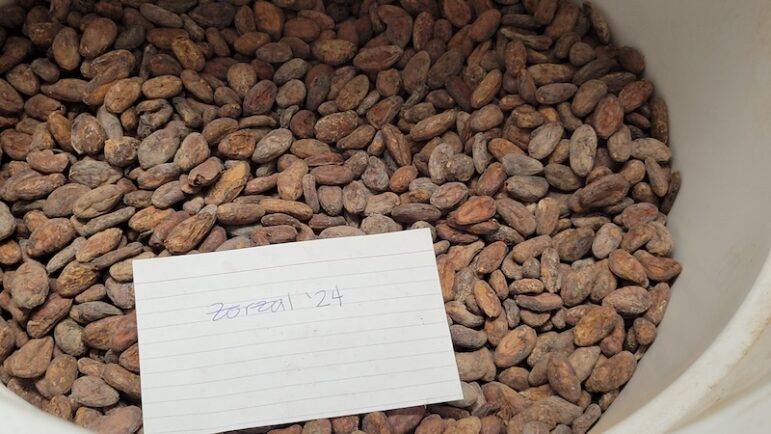

Vachon makes small batches of chocolate, less than 50 bars, using beans grown in Belize (Maya Mountain), Uganda (Semuliki), and Dominican Republic (Zorzal). Chocolate only grows within 20 degrees north or south of the Equator.

“The only state in the United States that fits in there is Hawaii. Those Hawaiian beans are very expensive, though, so I picked three beans that I really like, that are different enough from each other, and that I can play with to make other things,” Vachon said. “Like, I have a chocolate raspberry bar that I use the Maya mountain chocolate, and I lower the percentage down to, like, 68 so you can really taste the raspberry.”

The beans Vachon uses come from small producers that use ethical practices, and many of which are owned by women.

“Each one is from a specific cooperative where individual farmers who are paid properly for their product, don’t use child labor or use slave labor, and use high grade cacao and ferment it properly in the country of origin,” Vachon said. “They all bring their raw beans, and they’re fermented at these fermenters.”

Vachon has six standard bars, and sometimes makes special batches.

Her dark chocolates are 75 percent organic cocoa beans, along with organic sugar and organic cocoa butter.

“And then I do the milk chocolate, 60 percent milk chocolate, and I use the Zorzal beans for that,” she said, noting that the milk is powdered because liquid milk is water-based and would seize chocolate if used. “Then I have the white chocolate, pistachio, and then my last one is, because I love cardamom, I do a cardamom bar using the Semuliki bean. It’s still 75 percent but I swirl in cardamom at the end, and it has this wonderful cardamom taste that I absolutely love.”

Other limited editions include lemon espresso bar, pumpkin pie, sugar free milk, and oat milk.

Vachon finds inspiration from other chocolate makers.

“Everywhere I go, every city I visit, I’m like, ‘Where are the craft chocolate makers?’ And I try to meet them and go on a tour,” she said. “It’s just such a cool thing to meet them.”

Vachon has gotten to know other local chocolate makers, including another one in Watertown, Lori Shapiro, owner of Sueños Chocolate, who studied botany related to cacao and other products in Ecuador for her doctorate and got to know producers.

“She’s made this relationship with a particular farm and cooperative in Ecuador, and she’s their sole importer,” Vachon said. “She doesn’t use anyone else’s beans, and she just makes things out of it.”

One of the keys to being a successful craft chocolate maker is to find a niche. Vachon has lent her knowledge to a friend in Somerville interested in making chocolate.

“She’s starting a business making excellent kosher chocolate for the Jewish community. And that’s her thing, because she said that the kosher chocolate is awful,” Vachon said. “She wants to bring good kosher chocolate to the world.”

Vachon got into chocolate making after she retired from working in clinical pharmacy for many years. She doesn’t have visions of mass production.

“I did it so that I could do this, because I love it so much, you know, and I have that luxury to be able to do that,” she said. “I don’t want to be big. … People keep saying, ‘Oh, you’re gonna get in Whole Foods.’ That would be a nightmare for me. I’d be sitting down here like cranking out chocolate. I don’t want to do that. I want to make chocolate and enjoy it.”

Sotto Chocolate can be found at the Watertown Farmers Market, which runs from June to October, as well as at several stores and cafes in the area: Fastachi, Revival Cafe in Watertown, Cork & Board in Newton, Brookline Booksmith, and Life. Love. Cheese. in Wakefield.

Becoming a Chocolate Maker

Vachon’s journey to becoming a chocolate maker began when she received a melanger, which grinds the beans into a rich chocolate liquid.

“This is the one piece of equipment that you can’t make chocolate without,” she said.

Even with the equipment, she found that the trickiest part was tempering the chocolate: transforming the liquid chocolate mixed with cocoa butter, sugar and sometimes other things, and cooling it into a bar that is pleasing to the eye and the bite. When she started, she would do it the traditional way of tempering on a marble slab.

“It was absolutely a journey I had to take to learn how to do this,” she said. “But I spent a lot of time making chocolate that tasted good, but looked bad. And then (in 2018) I took a course from this online chocolate school called Ecole Chocolat.”

The class gave her a good baseline understanding about the chocolate industry, history, and some practical knowledge, but it was only online. She found another website called Chocolate Alchemy that has detailed videos about the chocolate making process.

“It was founded by John Nanci. He’s a retired chemist who decided that he was going to unlock the secrets of making chocolate for the small maker. And he has spent so much time and energy in his scientific method and chemistry background, really figuring out how to do all these steps and all the science behind it,” Vachon said. “He puts out tutorial videos. And so that was where I was deeply studying his videos and attempting to make my chocolate.”

Vachon was able to get “reasonably good,” but she still lacked the confidence to make it turn out the way she wanted each time. Then she discovered another chocolate maker in Oregon, Mackenzie Rivers, who owns chocolate maker Map Chocolate and runs workshops

“I just decided I was going to be brave and fly myself out to Oregon and take the class. It was a three day class: it was one day on roasting and winnowing, one day on melanging, one day on tempering,” she said. “I took this notebook with me that’s precious, now, where I took, like, a million notes, and I met other people like me who are making chocolate in their homes.”

Vachon took an in-person class with Rivers in 2019, followed by a couple of online courses during the Pandemic. She has gotten to know Rivers, and said that once you are her student you are always her student.

“She’s the most generous mentor to so many people,” she said. “And, I don’t think I’ve met very many mean people in the world of chocolate. So between her and other people, I just feel like I have this lovely network of people that we can all call each other and say, hey, my chocolate is acting like this. What’s wrong? And we can help each other out.”

The Process

Vachon gets large canvas sacks of fermented beans, which she stores in plastic buckets. She begin by taking a scoop of beans, and fishes through them to make sure there are no small stones, pieces of shell, or other items not wanted in the final product.

“These are really good quality beans. There’s not going to be a lot of yucky stuff in them,” she said. “But if you’ve got beans from commercial chocolate, like Hershey does, there’d be rocks and sticks and god knows what else‚ in there.”

She takes the beans and roasts 2.5 pounds at a time in what she calls “a tricked out coffee roaster,” which have a hole drilled in one side so a thermometer can be pushed through to measure the temperature of the beans while roasting.

The roasting process is part science and part art.

“So, chocolate, as it turns out, needs to be in a magic window for a magic amount of time for the roast magic to happen,” Vachon said. “So, I want it to be between 212 and 240 (degrees) for anywhere from two to four minutes. If I’m going for a light roast, it’s more like two minutes. Dark Roast, four minutes. So I typically go for three to four minutes.”

Keeping the roaster in that magic range takes some finesse.

“I got it kind of down to a little dance here,” she said, while opening the roaster door and waving a metal tray to blow in air to regulate the temperature.

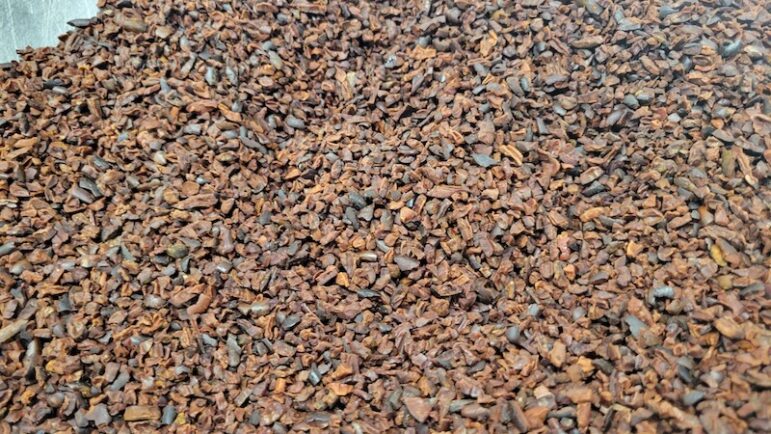

After the beans are roasted, and are cooled, she puts them through another rigged-up machine.

“This is actually an orange-juice juicer. Everyone uses this, this Champion juicer,” Vachon said. “You get them off of eBay. They aren’t even made anymore.”

The juicer cracks the shells and the vacuum that has been attached sucks out the lighter shells as the heavier cocoa nibs fall into a container.

Then she takes the nibs and puts them into the melanger to slowly grind them.

“So, for two days it is doing two things: conching and grinding,” she said. “Grinding is literally what it sounds like. It’s making the particle size smaller and smaller and smaller, because if you didn’t, if you ground it very little, you get a gritty chocolate. … And you want the cocoa bean particles to be, like, 20 or 30 microns or less. That’s what takes the time.”

Conching releases the volatile compounds, aerates it, and heats the mixture to develop the flavors in the chocolate, Vachon said.

While the nibs are in the melanger, Vachon adds other ingredients, such as sugar, and cocoa butter. She does not produce her own cocoa butter, which requires an industrial press to separate the butter from the cocoa nibs. Instead, she buys bags of more than 50 pounds of organic cocoa butter.

When the chocolate mixture in the melanger is the right consistency, it is ready for the tempering process.

“Temperature is super important for the different phases of chocolate, I can do the roasting and the melanging in a warm room, but when it comes to tempering, I need it to be a cooler room,” Vachon said.

She has an air conditioner to keep the room cool even while roasting beans, and a dehumidifier because chocolate making requires low humidity conditions.

When the conditions are right, he pours the liquid chocolate into molds, and allows them to cool and solidify. Then they are ready to be packaged and are ready to be sold.

Nice story about delicious chocolate! It’s cool to see all that goes into the making of chocolate — right here in Watertown!