The following articles are part of a series on local history provided by the Historical Society of Watertown. They were written by former Historical Society President Paul Brennan for the December 1989 edition of the Historical Society of Watertown newsletter, “The Town Crier.”

A PEN AND SHOVEL

On Friday, October 27, 1989 the Edmund Fowle House was visited by Archeologist Edward L. Bell from the Massachusetts Historical Commission. He came in response to a recent discovery at the Edmund Fowle House which at first appeared to be a large underground well in it’s backyard. The following account is taken from my diary leading up to this Historic meeting.

On Saturday morning, October, 15, 1989, I had a young visitor at the Fowle House. His name is Wayne Lyons from Waltham and the four-year-old son of two close friends of mine. I had been asked to watch after Wayne for a couple of hours. Wayne enjoys coming to the Fowle House because there are so many things to catch his attention. That morning, before he arrived, I thought of things we could do to keep our interest and at the same time, be educational. It was a dry but overcast day so I thought it possible to entertain Wayne out in the backyard.

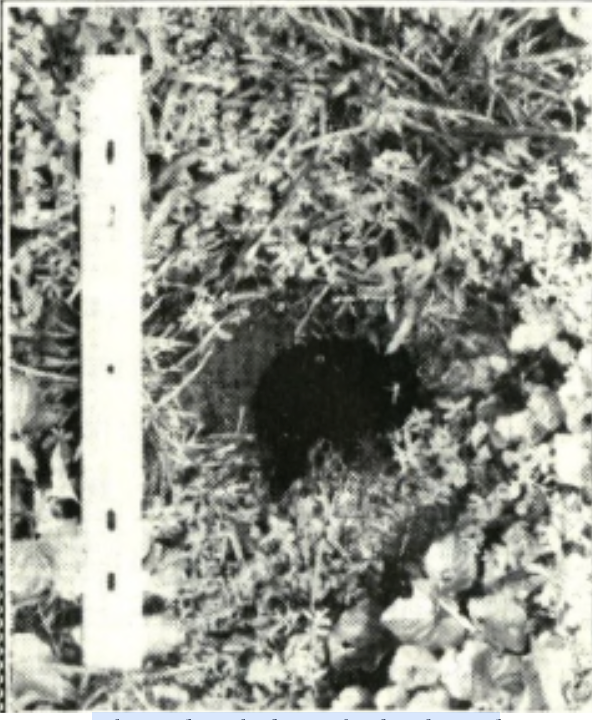

Over a year ago, while I was hanging out my clothes to dry on a line in the backyard, I literally stumbled upon a hole in the ground. It was overgrown by crab grass, and totally undetectable by sight. The hole was made by some type of burrowing animal and conveniently located at the base of the old crab apple tree. Upon my further inspection of the grounds surrounding this tree, I observed a good number of older, now covered holes in the immediate vicinity of the one I had just stumbled onto.

It was slightly intimidating at first because of the size of this rodent hole. It measured four inches in diameter, and tunneled a perfect 180°, two feet straight down into the ground. Although I had never seen any evidence of a furry backyard tenant, I thought it wise to monitor it for any signs of activity. A whole year has now passed, and I felt confident that the once active hole was now vacant.

Wayne is at the age in which he constantly wants to retrieve information. His vocabulary is substantial, and he is curious to know about everything that his eyes fall upon. What a perfect project for him to get involved in, I thought. This had all of the necessary elements to keep any child’s interest captivated. There was dirt, a little shovel to move it, and an abandoned nest waiting to be discovered just a few feet directly below us. He could ask all of the questions that popped up in his mind, and all I would have to say in response was, “I don’t know, let’s find out.”

We began our excavation by taking a number of measurements locating the hole and setting up a crude grid to guide our shovel. We were careful to dig a square hole along one side of the tunnel so that we would not fill it with the dirt we were moving; also that it would expose the tunnel for us to follow whenever it might change direction. We peeled back the top layer of soil and grass rather easily and found that the dirt below was able to be removed by hand.

After digging down about one and a half feet we came upon a layer of white ash. This was a normal thing to come across when digging in the backyard of a house older than sixty years. Some of the heating prior to 1930 was wood and coal furnaces, of which the Fowle House still has. (The furnace has since been converted to an oil burner.) [Editor’s Note: It is now a gas furnace.] The residents of the house would dump the burnt ash and rubble removed from the furnace into a shallow hole in the backyard.

The layer of ash was roughly four inches thick and loaded with all sorts of interesting things like old cot nails, broken pieces of ceramic ware, and evidence of burnt coal. Some of the broken pieces of ceramic ware were later identified as Henry Burgess porcelain made in Staffordshire, England between the years of 1864-92.

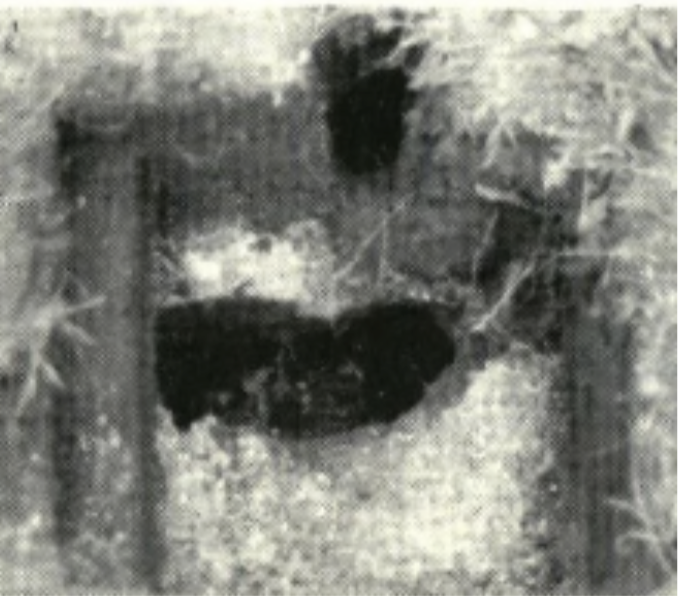

We continued to dig beyond the ash layer another foot before we struck a strange object. It seemed to me to be slate and was larger than the hole we had dug. The rodent hole ended at this level and seemed to continue on the slate shelf. After clearing the slate shelf from loose dirt

we discovered that the slate was in a number of pieces and had space enough to fit my entire hand through it. I gaged the thickness of the slate to be about three inches, and three feet from the surface from which we had begun our adventure. The space between the slabs of the slate shelf was dark and empty. I could not see a bottom. The hole we had dug was too deep to allow natural sunlight in, so I stuck the measuring tape into the space and was astounded to record another three feet from the bottom up to the slate shelf.

Wayne, by this point, had lost any interest in what we were doing while my heart was just beginning to pound with excitement. I knew his folks would be coming by soon to get him so I covered the hole with a large board and a number of bricks.

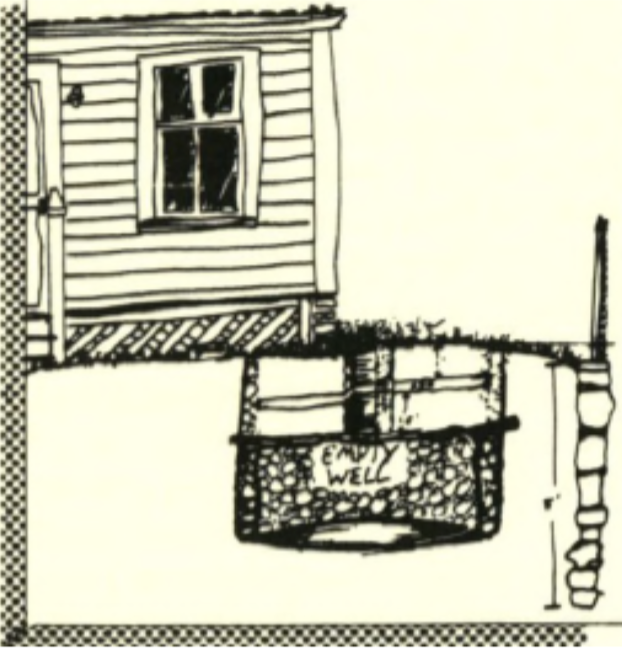

As soon as Wayne departed, I grabbed a flashlight and returned to what we had begun. When the light illuminated the space beyond the slate shelf there seemed to me to be no question of what it was that we had discovered. It was an old field stone well.

I called a meeting immediately between myself and two very knowledgeable Council Members, Barbara Yocum and Elmer Stinehart. We examined the discovery and decided to see what kind of professional help we could get from the Massachusetts Historical Commission. Although this

new discovery was fascinating, it was also potentially dangerous.

When Edward Bell arrived, I was eager to show him what was found, and he reciprocated by quickly lying down on his stomach and sticking his head down into the dug-out much farther than I would ever venture. He was surprised at the size of the well and estimated it to be five feet in circumference. He spent a good ten to fifteen minutes draining me for any other information I could offer before requesting to look at the inside of the Fowle House. I then briefed him on the history of the house, including the occupants since the building was moved in 1871.

He then examined the dirt cellar under the kitchen additions which were added to the Fowle House when the building was moved. There he found a number of other artifacts on the surface along with other visible evidence of what might be a connection between the house and our discovery. He compiled his notes from his visit for a while, and after his review began to educate me about the complications involved in acting on this matter.

In brief, we have discovered a type of time capsule which if excavated properly by a professional will yield a wealth of information never before made available about the history of this house and the great land that it rests on. Information from a time when people from this community lived a different style of life which to us, today, would seems like an entirely different planet.

The hole leading to the well has since been filled in on the recommendation of Ed Bell. This will keep our time capsule from becoming contaminated with foreign substances. A day will come when we will be able to reopen our time capsule and read it like a best-selling novel. And I hope to be the one holding both the pen and the shovel.