Part 7: What We’ve Got Here is a Failure to Communicate! More of the 1800’s

The 1800’s were more than just an industrial revolution in Watertown. Many national and local

issues were being played out locally to great drama and effect.

For instance, the Temperance Movement was in full bloom. In a few words, women had had enough of family beatings and earnings all going to the local tavern and not to feed their children. That issue, plus women’s suffrage and abolition seemed to draw people with like sentiments together, and Watertown was knee deep in these issues.

In 1842, Watertown hosted a State Temperance Convention. By 1870, the Baptists and the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) had joined forces to eliminate drinking in Watertown. As Hodges says, “So unpopular are the ‘dries’ that on occasion bottles filled with tar were flung through their windows.”

G. Fred Robinson, in Great Little Watertown, tells a similar story. In the mid 1800’s there were only three buildings in the Square that were three stories tall, the Spring Hotel, the Dana block and Able Hunt’s store. Abel rented out his upstairs hall to the Baptist Society for meetings, until he learned of their temperance sentiments.

Irate, he kicked them out and rented to another group. One of that group’s members bored a hole through Abel’s wall and siphoned off sherry from Abel’s sherry cask. Abel had an opportunity to rethink his stance on the Baptist Society.

Where Watertown Savings Bank is now, Samuel Noyes opened one of the first liquor-free grocery stores in Watertown, against the advice of many who thought his business would fail without alcohol. His business prospered. It may have helped that he was an important member of the Watertown Baptist community.

In 1880 Watertown voters voted “no” to local alcohol. By the early 1900’s a WCTU water fountain was installed in the Delta on the corner of Main and Galen Streets. The sale of liquor was prohibited, but not discontinued, as people found ways to continue imbibing.

The WCTU was involved in a variety of causes, including abolition and women’s suffrage. Here’s an excellent video explaining their movement and the barriers they faced getting women the right to vote:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WPczGnA7k9A

The Watertown Annual Report of 1882, lists an article for men to vote on: Article 8 reads as follows: “To see whether the town will, by its vote or otherwise, ask the Legislature, to extend to women, who are citizens, the right to hold town offices and to vote in town affairs on the same terms as male citizens.”

The 1900 Watertown Annual Report lists that at that year’s town election, 1,558 men voted and 29 women. Apparently, women were allowed to vote on restricted local issues, like schools. Massachusetts ratified women’s right to vote in June 25th, 1919. Watertown women voted in droves in 1920.

See this Watertown News article for the full picture of women’s suffrage in Watertown:

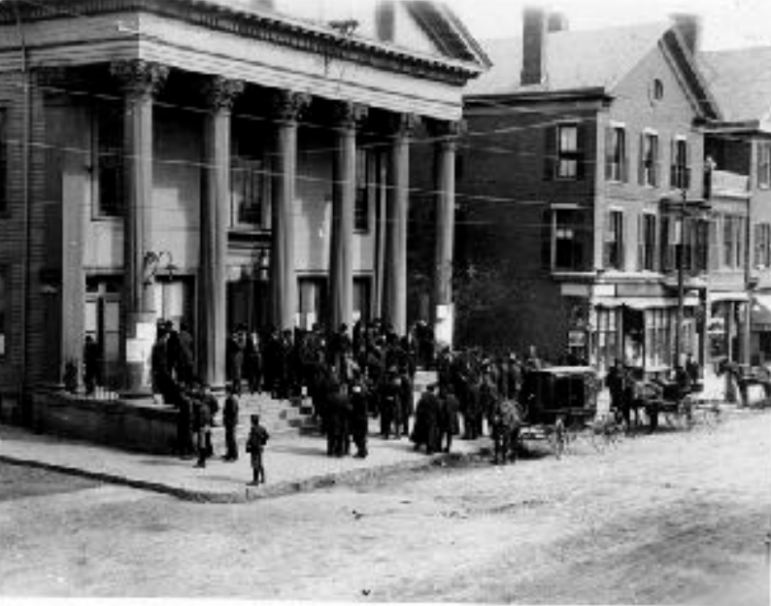

On Sundays, just one block down the street from the Delta (corner of Main and Church Streets), in the mid 1800’s, Watertown Town Hall was busy. There were two Congregational services, morning and evening, presided over by Dr. Lyman Beecher (Harriet Beecher Stowe’s father). He preached eloquently against the evils of slavery and drink.

In the afternoons, it was the Unitarians’ turn to meet, their services presided over by Theodore Parker. According to Hodges, “Parker espoused humanistic beliefs [of Emerson, Hawthorne and Margaret Fuller] and adopted the cause of abolitionism. He worked and wrote for peace, temperance, the rights of labor, and on behalf of those who suffered from poverty and injustice.” Before the Civil War, there were great debates on slavery and torchlight marches that devolved into fights in the streets. Wendell Phillips, a famous abolitionist speaker was denied access to Faneuil Hall in Boston for a speech. Watertown invited him to come to Town. Thirty Watertown men were sworn in to keep order for the night of the speech, because there was no police force at the time and there were threats that people would come from Boston to disrupt the proceedings. All was quiet.

Lydia Maria Child (sister to Convers Francis) and Maria White Lowell (married to James Russell Lowell and daughter of Watertown’s Abijah White) who were both acclaimed writers, stirred up sentiments with their anti-slavery tracts.

Lydia Maria Child discovered that she was as much reviled for her being a woman expressing an opinion than the opinion she expressed. Yes, this town was hopping in many ways! On a separate, totally unrelated note, do you know the poem/song that starts out “Over the river and through the woods, to Grandfather’s house we go?” Lydia wrote that.

Meanwhile, the factories kept chugging along. In Great Little Watertown, Robinson says, “The mill-owners of the period lived and worked close beside their factories. They took a personal, sometimes annoyingly personal, interest in their workers. They sincerely believed that, especially in the case of women workers, these long hours were necessary to safeguard the morals of the community.”

Robinson continues, “Citizens in 1855 passed a special resolution to enforce the truancy laws, but economic hunger was too strong a force, and child labor was not wholly prevented. One little girl of nine, who already knew how to read and write, was put to work on the plea that she was twelve and the family in great need, so the manager took her as a favor knowing the family circumstances.”

It seems that the more things were changing, the more they were staying the same. With the development of the Park Movement, things in Watertown Square, at least, were about to change in a very big way. Watertown was about to reinvent itself again.

Next: Part 8: The 1900’s, or A Walk in the Park

Part 8: The 1900’s or A Walk in the Park

“And this is good old Boston,

The home of the bean and the cod,

Where the Lowells speak only to Cabots,

And the Cabots speak only to God.”

— Origin Uncertain

It’s the dawn of a new century, but struggles remain. The Temperance Movement is in full swing. It’ll be 1919 before the Eighteenth Amendment is ratified by the states. In 1933, the Twenty-first Amendment will be ratified. That will repeal the Eighteenth Amendment, allowing alcohol to be legally manufactured, sold and consumed in the United States again.

Women are closing in on getting the right to vote. By 1920, the Nineteenth Amendment will be

ratified.

The Civil War has ended. The North won, but the work of freedom is still unfinished. The Jim Crow era will last well into the 1900’s. Challenges remain.

Child Labor Laws: In 1852, Massachusetts became the first state in the union to have compulsory school attendance laws. Around the 1870’s Massachusetts is leading the way in saying that kids need to go to school full-time, no matter the poverty level of their family.

There’s a new movement afoot, the Parks Movement, and Frederick Law Olmsted and his work in Boston are major contributors to the local fervor for more parks.

Here are some of the major principles, as I understand them:

- The industrialization of this area and the overcrowded conditions require parks.

- The idea that a well-designed park might improve the populace’s physical and mental health.

- The idea that parks are democracy at its core … everyone can participate.

- The American Medical Association claimed that parks cleansed the air and benefitted citizens nearby.

- At that time, there was such a need for park space that people utilized cemeteries for that purpose. Mt. Auburn Cemetery was a good example of this.

- Belief: First class parks made first class cities.

- An emphasis on more naturalistic than embellished parks was stressed (very little statuary, etc.)

Watertown enthusiastically jumped in, creating a Parks Department in 1895. Saltonstall Park is the result of the Parks Movement, but it looked very different than it does today. For instance, it had a stream running through it back then.

Meanwhile, as hard as this may be to believe for us living in Watertown today, the Atlantic Ocean still flowed into the Square and then receded twice a day, leaving a mess in its wake. With the Parks Movement in full swing, that was about to change, and a man named Charles Eliot (a landscape architect and a business partner of Olmsted’s) will lead the effort for a multi-municipal plan to “green up” waterfront land in Newton, Watertown and Boston by acquiring it and designing parks. It was a big idea, and Eliot was just the guy for the job. With the right connections, smarts and talent, he and the rest of the Metropolitan Parks Commission was going full speed ahead.

See this link with more about Charles Eliot and the Charles River Conservancy.

https://thecharles.org/about/history/

In sum, this was a movement of the gentry. They weren’t just focussed on the Boston area. For

instance, they reinvented Revere Beach as well. The Commission took day long “field trips” on boats and trains from community to community, taking notes and eating lunch and discussing ideas for how to reclaim, and reuse land for the public. In all, by 1895, 7,000 acres within a 10 mile radius of Boston had been acquired for the Metropolitan Park Commission system.

The first step to making their plan along the Charles River work was to “tame” the Atlantic Ocean. But first you had to deal with the politics. In Boston, people on Beacon Street were worried that if land was filled in along the Charles River Basin, they would no longer have waterfront property (if you could call it that).

In the Metropolitan Park Report of 1898, it is stated: “In any planning of this sort we are, of course, greatly embarrassed by the uncertainty as to the future conditions of the river, whether its banks will continue to be alternately exposed and flooded by the tide, or whether the proposed dam will be built to convert it into a fresh-water stream like the reaches above the Watertown dam.”

After a multi-year political battle (where it was also alleged that Harvard and MIT just wanted the dam, because then they could row in the Charles River Basin), the project got approved. On October 20, 1908, the gates of the dam went down, and the Charles River Basin was born. Here’s a short walk-around talk about of what was done:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C1HLqy_Fqvs

And, as for Watertown Square? Change, again, was on the way! It was all a high stakes jigsaw puzzle, and in the end, it seems to me, there were more winners than losers.

A few other pieces of information:

A video by the Newton Conservators set on the Watertown/Newton line, highlighting what they were doing and planning to do along the river, all work started by the vision of Charles Eliot and his group:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YwMeVxIvtEs

How the Charles River Dam Works Today:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TA8LG9kp47E

A recent Watertown News article on the possible dismantling of the Watertown Square Dam:

Next: Part 9: There’s a New Bridge in Town