By Linda Scott

Watertown Resident

Part 5: The Roaring 1700’s

By the 1700’s, Watertown was hopping. There were stage coach lines coming through town and a lively lumber business floating up and down the Charles. Besides the mills, there were hotels, stables, blacksmiths, and horse boarding establishments. (Burke)

Situated right in the middle of Watertown Square, Galen Street was proving to be kind of a problem.

At this point in time, which was surprising, because Watertown was still mostly a farming community, this square was a lively place, and not always in a good way. Watertown, as most American colonial villages, relied on alcohol, because water sources could be unhealthy and hold diseases. But Watertown seemed to view drinking as a must have for every occasion.

In a chapter Charles Burke calls “Happy Hours in Watertown,” in The Watertown Papers he says

that: In the 1700’s rum was required for decent funerals. The Town paid for it at pauper funerals as well.

Selectmen meetings were always held at a tavern, and Town reports of their consumption still exist. (Not to be accused of being partial, they rotated their meetings around the four taverns in Town).

At town meetings, rum and punch were the desired drinks.

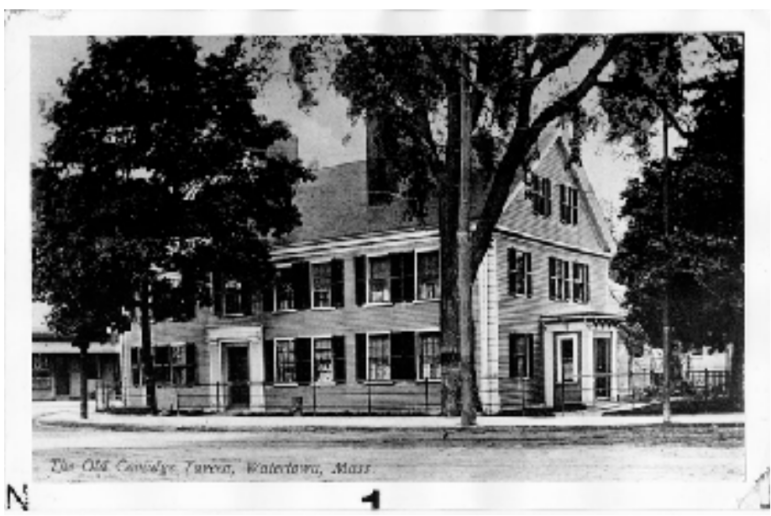

Before they sent the boys off to Lexington (although we know that they ended up late and in Arlington instead) on April 19, 1775, the Town treated the militia to drinks at the Coolidge Tavern.

At the time of the Revolution, Watertown had four taverns and four retail establishments for under 1,000 people. One of the most famous drinking establishments was the Coolidge Tavern. It was where the MBTA car barn is today. It’s said that George Washington slept there (and complained about the bugs afterward).

Just across Galen Street, on Watertown Street, Paul Revere and Benjamin Edes were hiding in plain sight from British soldiers at the Cook House. Boston was just too hot for these patriots! Watertown is where Revere engraved the plates and printed the money for the Revolutionary government. Meanwhile, Benjamin Edes had brought his printing press up the river in the cover of darkness and was busy writing and publishing the Boston Gazette, which advocated for the Revolution.

Fast forward to 1897. Mary Morse, who then owned the Cook house, thought that she had no use for this large house and wanted to avoid paying taxes on it. She had it torn down.

Back to drinking…

At the installation of a minister at the town church in 1780, 10 and a half gallons of spirits, two gallons of rum and nine gallons of wine were served.

The Town even provided spirits for firemen at fires until 1840.

It is said that in 1759, Lord Jeffrey Amherst, on his way to fight in the French and Indian War, camped on “the dirty green” (a boggy patch of land by the river close to Howard Street in Watertown) on his way to Lake George. His troops had been on shipboard in Boston for three months and were beginning to get restless. The dirty green “exposed his troops to fewer temptations” it’s said than the Square. It doesn’t say where Lord Jeffrey stayed, however.

Even into the 1800’s Galen Street was a rough and tumble place. In an article in the Watertown Enterprise it says, “We are in receipt of a lengthy communication in which the writer claims the police protection for Galen Street is insufficient; that the thoroughfare is almost any night the scene of disgusting and insulting practices …” Yikes!!

This extended way into the 1800’s. Burke says, “The Town of the 1850’s seems to have worn two aspects, resulting perhaps from its dual character as a residential town and a factory village. An old man in later years recalled his first sight of Main Street from the west at sunrise on a summer morning as a scene he would never forget … a wide road, elms meeting overhead, with comfortable houses on each side, their owners starting about their daily occupations.”

“Another writer described the approach to the village as a scene of tumbled down shanties with bleary eyed drunks staring from doors. He must have entered from another road, Galen Street, perhaps.” – Charles Burke (Watertown Papers).

Next: Part 6: How does our Delta Grow? The Industrial 1800’s

Part 6: How does our Delta Grow? The Industrial 1800’s

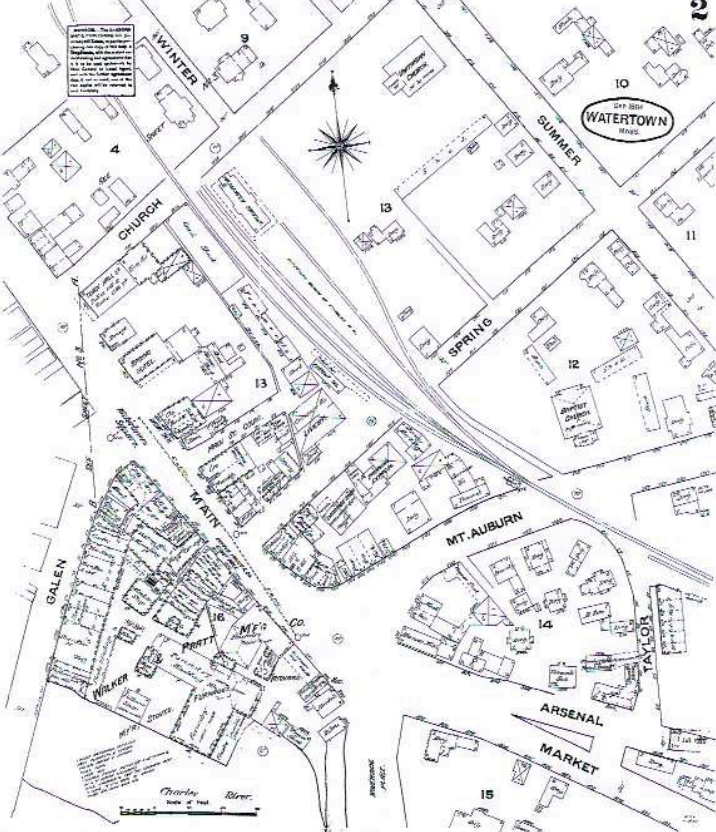

Business and industry were taking over the Square in the 1800’s. Notice in the map above that Mt. Auburn Street stops at Main Street, and where the Delta is today is covered with buildings and businesses.

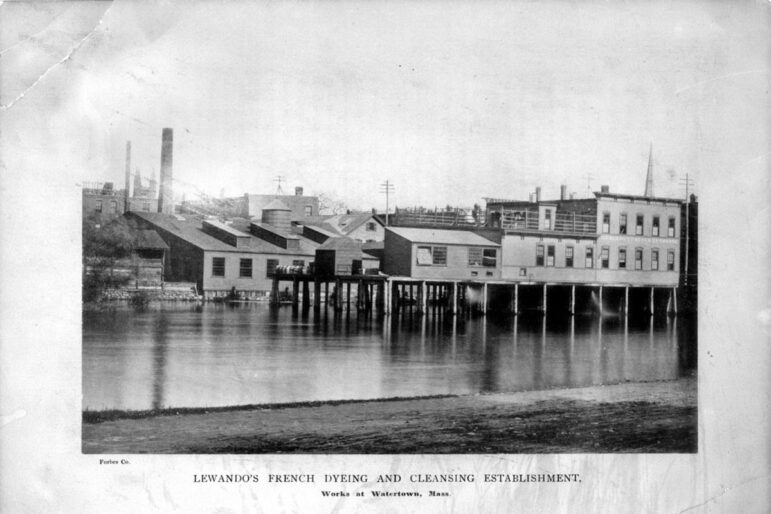

One of the bigger businesses in Town was Lewando’s, located right next to the river, (not on the map) that employed about 150 people a year. It was said that you would know what colors Lewando’s was using that day by the color of the river.

The grist mill had been moved from closer to the river to Main Street on the Delta in 1800. The Walker and Pratt Company occupied most of the Delta. Their buildings were built on the Delta in 1855. Part of its business, the molding room, was right next to the grist mill on Main Street. There was also a long brick storage building on Galen and a very large foundry on the Delta. They had wharves on the river for transport of stoves and building materials.

Miles Pratt was the original owner. His partner, Arthur Walker, came later. By 1861, only six years after he had built his company on the Delta, Miles Pratt retrofitted his business to manufacture cannonballs instead of stoves for the Civil War effort. He and his employees made a very valuable contribution to the North. After the war, they went back to making their actual product, the Crawford Stove, which was said to be the elite of stoves.

Watertown News recently had an article on Miles Pratt:

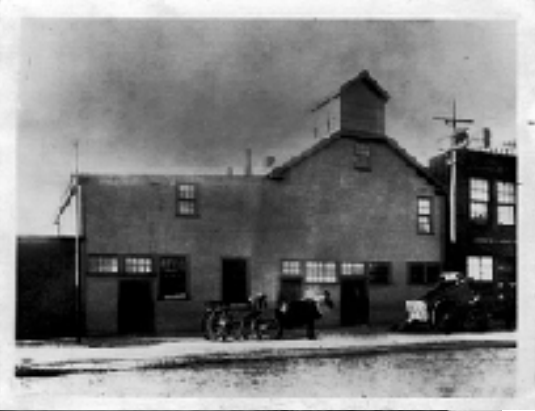

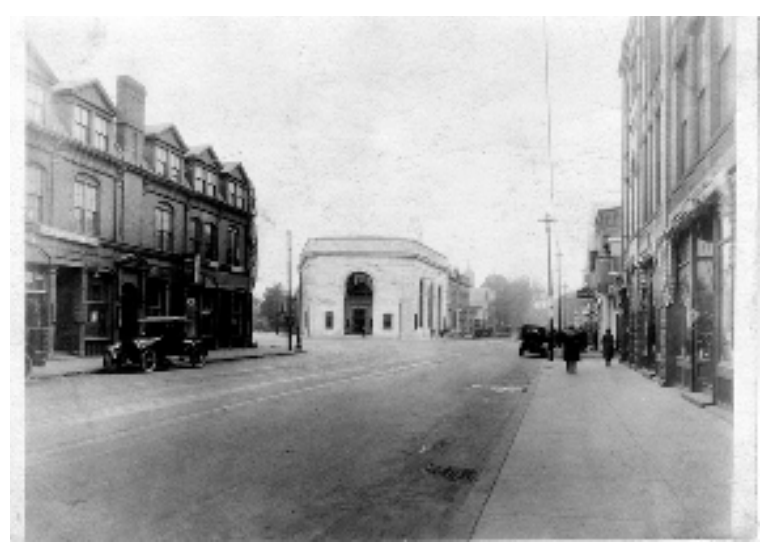

Above is another of Pratt’s buildings, a warehouse (the large building to the back left) on Galen Street. Moving along, we’d see the Barnard Block on the Delta (the corner of Galen and Main Streets).

Above is another look at Barnard Block on Main Street on what is now the Delta (left). It looks different, because the dormers were added in the 1890’s. (see David Russo’s research: http://www.davidjrusso.com/architecture/brigham/buildings/AddressSummary.php?id=13161092575670).

This block was demolished in 1925 to add to the Delta. Do you see a familiar building in the distance?

The Whitney Paper Mill was very near the Delta, where Pleasant Street is now. An employee designed a machine to make paper bags in 1857. Business soared. E.A. Hollingsworth became Whitney’s partner. The mill was now called Hollingsworth and Whitney. They added on a 200-foot-long building, upgraded to steam power, since water pressure wasn’t enough, and maintained an output of four tons of paper a day. It claims to have manufactured the first flat bottomed paper bags. It merged with the Scott Paper Company in the 1950’s. Here’s a more complete history of this company:

https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1653&context=mainehistory

Note: the Smithsonian gives credit to Margaret Knight for creating the first patented paper bag machine. If you want to see what it looked like, here it is: https://www.si.edu/object/patent-model-paper-bag-machine%3Anmah_214303#:~:text=Margaret%20Knight%20(1838-1914),for%20the%20invention%20in%201879.

So, between the overwhelming growth of industry on the Watertown Square Delta and along the Charles River itself, it must have been a daunting sight.

In Historical Notes of the Charles River, Ralph Perry writes: a contemporary observation: “As one approaches Watertown over the ancient bridge, he is struck by the appearance of the massive buildings on the right, with brick walls and their solid substructure rising, apparently out of the midst of the river …”

It’s 1885. Watertown is fully industrialized, and yet … there’s an article in the Watertown Enterprise on November 18th with the title: “One flock of 300 Geese Driven Through Town.” The article goes on to say: “Last Tuesday, another flock of 300 live geese were driven through Main Street. It was an odd sight and and attracted more or less attention. Mr. E. A. Brown had purchased them at the stock yards from parties who brought them from Canada to fill orders that he had given more than a year ago. They were driven to his farm on Main Street, where they are placed in pens and fattened. It takes about two weeks to prepare them for the market. To those who will take the trouble, a visit to Mr. Brown’s farm will more than repay them. You will see there a sight that few have the opportunity of seeing. There are now on the place over 1,000 live geese …”

It seems that Watertown’s double identity as both a city and country community was still the

order of the day.

Next: Part 7: What We’ve Got Here is a Failure to Communicate! More of the 1800’s