The following story is part of a series on local history provided by the Historical Society of Watertown. It was written by Historical Society of Watertown board member Mary Spiers. Mary served as our Recording and Corresponding Secretary for several years. (Mary retired from the Board in January 2923 but is still a volunteer. She wrote this article for our January 2013 newsletter, “The Town Crier.”) Information concerning what appears to have been a significant political clash over using the stockyards for the export of war horses was gathered from the archives of the 1915-1916 Boston Globe and the Watertown Tribune-Enterprise.

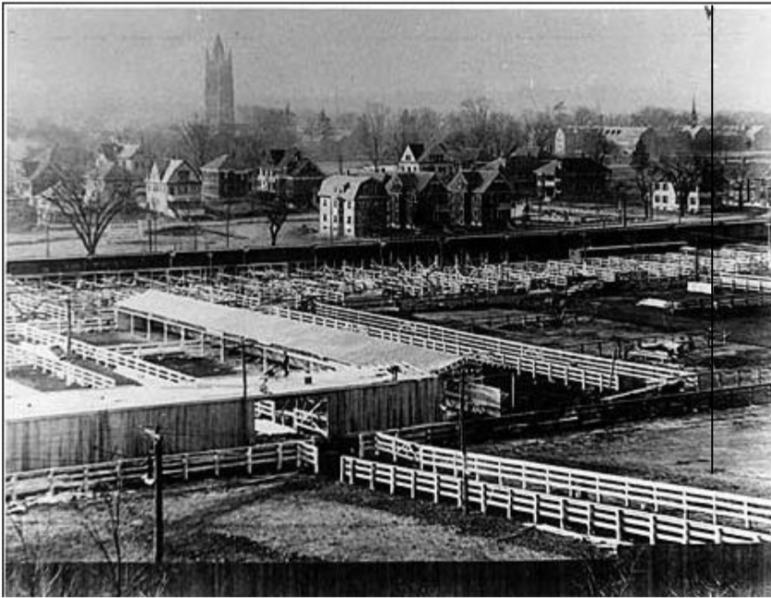

Did you see the movie “War Horse”? Did it ever occur to you that there might be a connection between Watertown and those brave cavalry horses of World War I? Maud Hodges wrote in her manuscript “The Story of our Watertown” (1956), “After the start of WWI in 1914, thousands of little shaggy Canadian horses and mules filled the Union Market Stockyards, and snow whitened their backs in the open pens.” The horses were there at the arrangement of the Canadian and French governments. They would rest briefly at the yards between railroad car and steamship to St. Nazaire, France.

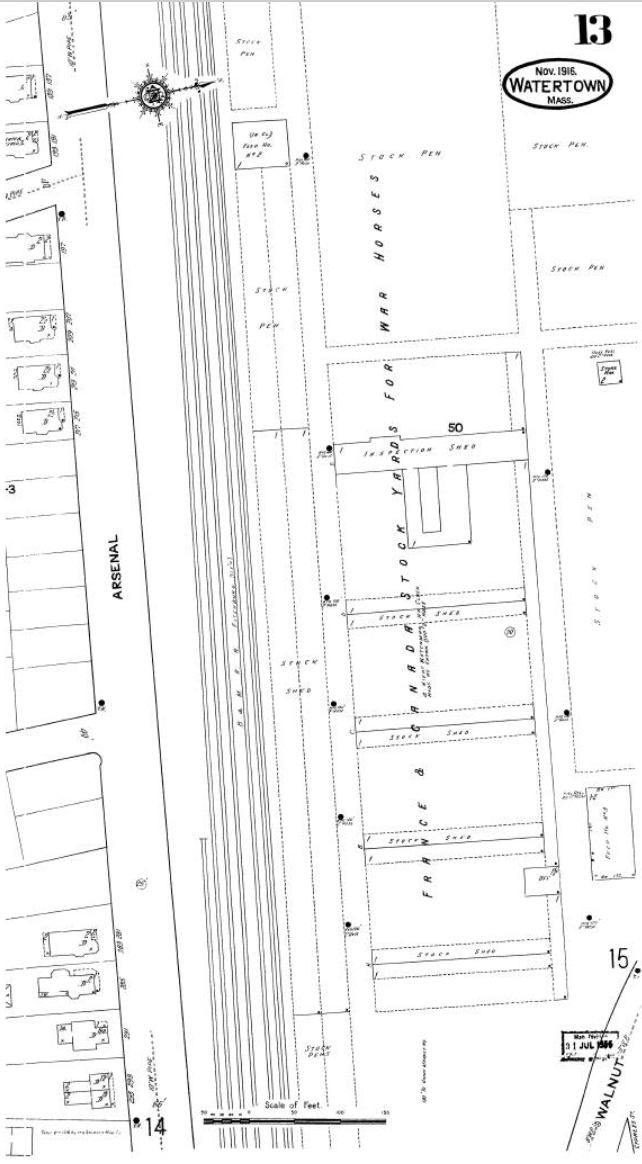

The stockyards were located in a 28-acre triangular tract of land between Arsenal, Franklin and Walnut Streets. They were built in 1873 for the Fitchburg Railroad which used them in collaboration with the Boston and Lowell Railroad. They were initially developed as feeding yards for cows and sheep and as such had feeding mangers and watering troughs with excellent drainage. The large near-by Union Market Hotel catered to the stockyard trade. By the start of WWI, the stockyards were owned by the Boston and Maine Railroad and by 1916, neighbors to the yards began to complain of noise and health concerns caused by the thousands of horses arriving and departing from there. The B&M Railroad’s contract “to keep no more than 3,000 horses at a time” was revoked at a Town Meeting.

The Watertown Board of Health requested the right to hire an outside lawyer to deal with the railroad rather than use the town lawyer, Wesley Monk. The B&M Railroad inspector told those interested that the “the yards had been repaired, cleaned and painted and that all animals held there were in good condition, none sick.” The railroad continued to unload horses much to the chagrin of the neighbors. Maud Hodges related in her “The Story of Watertown,” how one Walnut Street resident fully aware of what was going on, “sat up until 2:00 a.m., only to learn on rising that the unloading occurred at midnight … without noise.”

What exactly were the health concerns on the minds of Watertown citizens? The winter of 1915/1916 had seen a wide-spread epidemic of foot and mouth disease affecting all of Massachusetts. By June of 1915, two places in the state were under surveillance by the U.S. Department of Agriculture: the Brighton Abattoir and the Brighton Stockyards. Watertown came under “the ban of pestilence” i.e., foot and mouth disease, with only two cases. The June 23, 1915 Watertown Tribune Enterprise stated that the Watertown cattle industry was affected to a very minimal extent.

By late June of 1915, the J.C. Keith, Stevens and Sweet Horse Company of Brighton asked permission to keep horses in the old stockyards at Union Market. The horses had been purchased by the English government in Canada and the U.S. to be shipped by Mr. Keith to France.

The horses kept arriving, only the B&M Railway’s original state charter to use the Union Market Stockyards for cattle could not be located since the yards had been out of use for a few years. According to the Act of 1902, the Board of Health or the town Selectmen had the authority to grant a permit to keep more than four horses at the yards, provided all the animals passed inspection by the town veterinarian to insure they were free of disease. Mr. Keith said that there was a British veterinarian at the site attending to and inspecting the horses daily. Dr. Jesse Humphreville, the town vet, said that he had examined the horses and found them in good condition. He assured the Board of Health that there was “no menace to public health.”

About this time, a number of residents spoke up in favor of the yards being used for horses and one of the supporters included Fire Chief John O’Hearn who believed the regular use of the yards would lessen the fire hazard. The July 9, 1915 Watertown Tribune Enterprise reported that the Board of Health granted J.C. Keith and Co. the right to keep English army mounts at the old Union Market cattle yards “for a period of 30 days and would allow for a renewal of the permit at the end of that time.” The Board of Health gave permission to keep not more than 150 horses at a time.

By December of 1915, news of Watertown’s dissatisfaction with the quartering of horses, reached other communities (i.e., Manchester, NH; Framingham, Reading and Quincy) who were eager for the business. The Watertown Tribune Enterprise took the side of the experts who favored the horses and stated, “Thousands of dollars are flowing into the banks of New York and New Brunswick, money that should now be on deposit in the banks of Watertown.” In this way the paper rebuffed the Board of Health and argued for the tax-paying B&M Railway.

At the January 24, 1916 Town Meeting citizens voted to permit the housing of the horses by the B&M Railway and the vote was 343 to 130, giving the railway permission to keep not over 3,000 at the Union Market Stockyards. Again, the February 8, 1916 Town Referendum refused to allow the Board of Health to take any legal action against the railway with 954 votes for the horses; 367 against.

From the beginning, Chair of Selectmen, G. Frederick Robinson and his son-in-law, Warren W. Wright, Chair of the Board of Health, both Republicans, were in the fight against the horses. However, not all Republicans were in agreement with these leaders. Some thought Watertown could benefit from the venture, i.e., the $100,000 in tax revenue from the Boston and Maine and envisioned the town as an industrial center near the Port of Boston. The March 7, 1916 Boston Daily Globe reported the defeat of the opposition: “Horse Base Men Carry Election.” The March 10, 1916 Watertown Tribune Enterprise headlined: “One-Man Government (i.e., G. Frederick Robinson) Routed by Overwhelming Majority.” By June of 1916, the war horses headed for France were now out of the limelight. President Wilson’s problems with Poncho Villa’s border raids took their place. As the world war wound down, the solemn toll taken by the Spanish Influenza filled the news. The Watertown war horses continued to use the stockyards as a resting station as they faded into history as the champions of the cavalry on the European front.

It’s “Pancho” Villa, not “Poncho”, a poncho is a piece of clothing. I hate to be that guy but I just can’t help it…LOL

These historical pieces are very welcome. Kudos to Mary Spiers!