The following story is part of a series on local history provided by the Historical Society of Watertown. It was written by Historical Society of Watertown board member Bob Bloomberg. Bob is also on the board of the Watertown Historic District Commission. He is a genealogist (his contact information is on our website) and has written several book reviews and newspaper articles. He wrote this article for our July 2020 newsletter “The Town Crier.”

Pop quiz: What do Hiram and Alfred Hosmer, P. Sarsfield Cunniff, and James Russell Lowell have in common? The answer is they are the people that the three Watertown elementary schools are named for. But who were these men, and why were they honored by the town? And, intriguingly, a strong case could be made that, in a more recent era, two of the schools might have been named for a woman.

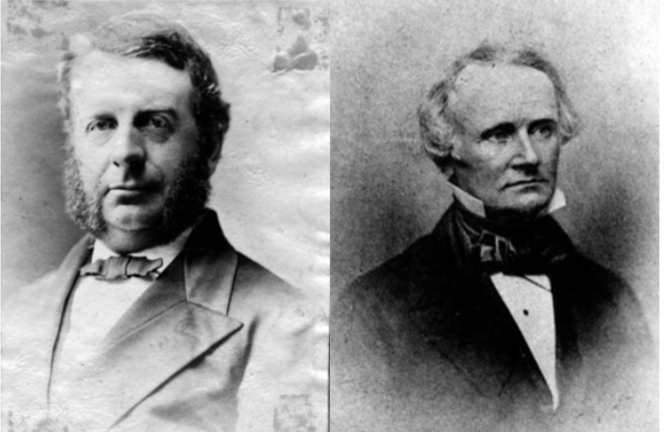

The Hosmer School

Dr. Hiram Hosmer moved to Watertown after graduating from Harvard in 1824, and practiced medicine in the town until his death in 1862. Little is known about him, but he was remembered as having great professional tact and good judgment. A contemporary wrote that he was not a bookman, but a diligent student of nature who studied the diagnoses of his patients carefully. He was, it was said, not afraid of powerful medicines when really needed. Hiram’s nephew, Alfred Hosmer, opened his own medical practice in Watertown in 1857, a year after he received his M.D. from Harvard. Solon Whitney’s article on Watertown in the History of Middlesex County records Alfred’s career at length. He was a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and a member of the State Board of Health, Lunacy and Charity, and President of the Obstetrical Society of Boston. He organized and was the first President of the Massachusetts Medico-Legal Society. And, he served as the Medical Examiner for Middlesex County.

It was likely Alfred’s service to the town that led to having a school named for him. For six years he was a member of the School Committee, serving as Chairman for two years. He was a member of the Board of Trustees of the library for ten years, and a Trustee of the Watertown Savings Bank, where he was President for sixteen years. And, he was one of the organizers of the Historical Society of Watertown. Alfred was also a deeply religious man. According to the Watertown Town Report of 1870, Hosmer strongly favored keeping the Bible an integral part of a public-school education.

Alfred died in 1891. The Hosmer School was opened in 1900, at a cost of $43,000. It was built to relieve overcrowding in the schools in the east part of town occasioned by the expansion of the Hood Rubber Company and the Walker and Pratt Manufacturing Company. The School Committee did not give a reason why they chose to name the school after the Hosmers. Alfred was certainly deserving of the honor. But his niece, Hiram’s daughter, may have been equally worthy.

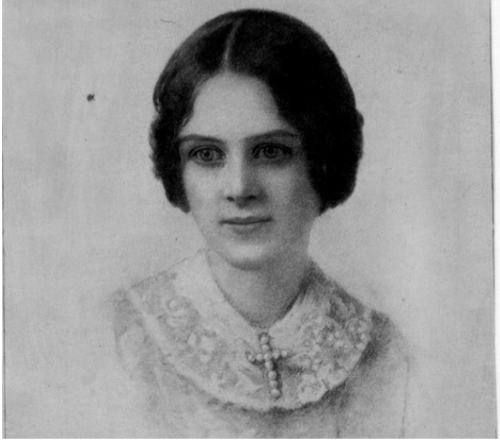

Harriet Hosmer was born on Riverside St. in Watertown in 1830. Her father encouraged her artistic passion, establishing a studio for her, where she sculpted “Hesper,” currently at the Watertown Library, along with several of her other sculptures. She tried to study anatomy to pursue a career in sculpting, but women were not allowed into anatomy classes. Finally, with the influence of a classmate’s father, she was admitted to Missouri Medical College. Like many artists, she headed to Rome, Italy. There she perfected her skills as a neoclassical sculptor, and

became one of the most distinguished female sculptors of the 19th century. While in Rome, she

associated with a group of artists and writers that included Hawthorne, Thackeray, George Eliot,

George Sand, and the Brownings. Hawthorne partly based his character of Hilda in The Marble Faun on Harriett. Her work was exhibited throughout the country and in Paris and London.

As the National Museum of Women in the Arts put it:

“Harriet Goodhue Hosmer defied 19th-century social convention by becoming a successful sculptor of large scale, Neoclassical works in marble.”

She was also a technical innovator. She designed and constructed machinery, and developed a process for turning limestone into marble.

It was exceedingly rare for a school to be named for a woman in 1900, and in any event, Harriet did not die until 1908, well after the school had been named. But it is fitting to remember Harriet as well as Hiram and Alfred when we think of the Hosmer School. [NOTE: When the new Hosmer School was dedicated in 2022, Harriett’s name was added along with Hiram and Alfred]

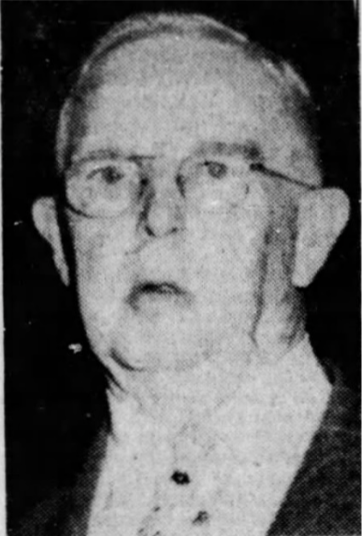

P.(atrick) Sarsfield Cunniff School

Sarsfield Cunniff epitomized the Horatio Alger success story. One of eleven children of Irish immigrant Martin Cunniff and his wife, Mary, he rose from post office clerk to lawyer to civic leader to Presiding Judge of the Waltham District Court. Along the way, he held nearly every town office in Watertown, and was a nationally renowned expert on juvenile delinquency, and a leading reformer on how young offenders were handled in court.

Cunniff was born in 1874 in Watertown, and lived here until his death in 1953. He graduated from Boston College and earned his law degree at Georgetown University. At the age of 29 he was elected to the School Committee for a three-year term, and was reelected three years later. He became the Chair of the Committee in 1904. One of his first subcommittee appointments was to select a site, and procure plans, for a new 10-room grammar school. By 1908, he was elected to the Board of Selectmen, Overseers of the Poor, and Surveyors of Highways and Appraisers. A lifelong Democrat, he served on the Democratic Town Committee, and was elected as a delegate to the state convention. For many years he served on the town’s Finance Committee. When Watertown’s form of government changed in the 1920s, he was elected a Town Meeting member, and later served as its moderator.

Not content with a private law practice in Newton and several public offices, in 1922 he became Chair of the Municipal Building Committee, and was elected a Trustee of the Public Library in 1928. He retained an intense interest in the town’s public schools, although he was childless. He often worked on questions regarding school finances, overcrowding and the need for new schools.

Cunniff tried to expand beyond the town. He ran for State Representative, and won in 1923, while also serving as the Town Counsel. He was supported by Democrats and Republicans alike. But he was quite outspoken, and a rift developed between him and the Republicans, as a result he was defeated in his reelection attempt. Thereafter, his focus remained fixed on two parallel interests: the welfare of his home town and its schools, and the welfare of juvenile offenders.

In 1928, Cunniff was appointed by Governor Alvin Fuller as a judge in the 2nd District Court of Middlesex County, based in Waltham. Governor Fuller was a fiscally conservative and socially progressive Republican, which — except for the Party designation — described Cunniff.

He quickly became nationally known for his innovative work with juveniles. Through his understanding of the problems facing youth, and his patience, he was able to reduce cases in his district by one half, while cases in other areas tripled. He instituted monthly night courts in 1937 so that parolees would not lose a day of pay when meeting with their parole officers. He installed court chaplains, and created the Waltham-Watertown area Council for Youth Protection and Guidance. In 1934, he was named Presiding Judge of the Court by Governor Joseph Ely, a Democrat.

Perhaps his most progressive approach to juvenile crime was to offer alternatives to jail time. He believed in the innate decency of people, and was willing to give them a second chance. For example, in 1937, seven students were arrested for circulating pamphlets urging employees of the Hood Rubber plant to organize a union. This was illegal, but he let them off, saying, according to one of the students, that it was a laudable cause.

The values he learned as a child of the 1800s remained with him all his life. In the 1950s he railed against the excessive violence that children saw on TV and heard on radio. He disapproved of girls wearing dungarees — too boyish looking. He believed magazines and comic books were too lurid, too full of sexual content. So, he led the fight against their distribution (not their censorship) to keep them out of the reach of children through cooperation with retail news dealers.

With this history of service and dedication to children, and the coincidence of his death the prior year, it was logical and appropriate to name the new elementary school built in 1954 in his honor.

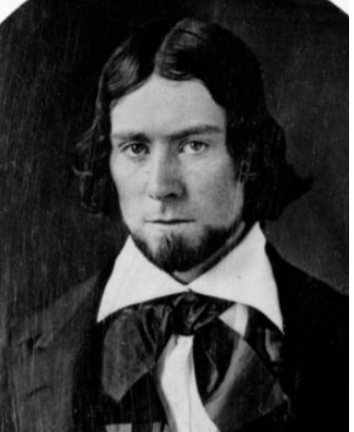

James Russell Lowell School

The nationally renowned poet, essayist, and satirist James Russell Lowell was a leading literary figure of 19th-century America. During his lifetime, which spanned most of the century, he was considered on a par with Longfellow and Whittier. The three became known as the “Fireside,” or “schoolroom” poets. They used conservative, traditional forms, paid strict attention to rhyme and meter, and employed moral, religious and political themes. Lowell’s works were frequently used as school texts.

Perhaps his two most popular poems were “Vision of Sir Launfel” and “A Fable for Critics,” both written in 1848. The first extolled the brotherhood of man, and the latter was a witty evaluation of contemporary American authors.

For twenty years, Lowell was a professor of Modern Languages at Harvard University, succeeding Longfellow in that position. During those same years he was editor of the Atlantic Monthly, and subsequently the North American Review. According to the Encyclopedia Britannica (on-line edition), his major significance lay in his helping to develop interest in literature in the United States.

In 1877, he was appointed Minister to Spain, and three years later he became Ambassador to Great Britain, a post he held for five years. He was described as charming and deeply learned, attributes that stood him in good stead as a teacher, editor, and representative of his country.

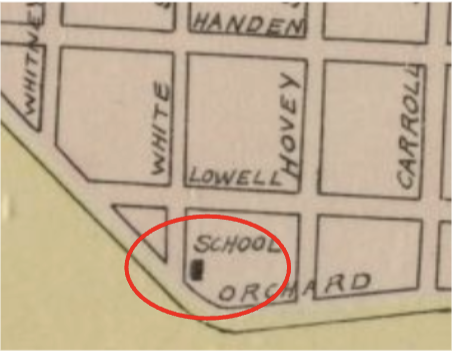

The first Lowell school opened in 1883 at the corner of Orchard and White Streets. It was demolished and the current school built in 1927. James Russell Lowell was worthy of the honor of having a school named for him. But there are several reasons why that honor might well have been bestowed on his wife if she had lived longer, and in another era. Lowell met William White while at Harvard. William was the son of Abijah White, one of the wealthiest men in Watertown, and the father of Maria White. Lowell visited the White mansion frequently, and there he met Maria. They married in 1844. For the next nine years, until Maria’s death from tuberculosis in 1853 at the age of 32, they lived in Cambridge.

Maria White Lowell was an accomplished poet, ardent abolitionist, women’s rights activist, and, by James’s own admission, the greatest influence on his life and writing. He said she was made up, “half of earth and more than half of heaven.” In his poem “Irene” published in 1841, he said he owed all its beauty to her. She was, he said, a woman of open heart and quiet charity, whose whole thought was “how to make glad one lowly human hearth.” She “set his spirit free.” Longfellow, whose child was born on the same day as Maria’s death, wrote:

“Two angels, one of life and one of death

Passed o’er our village, as the morning broke.”

Maria attended the first “Conversation” that was organized by women’s rights advocate and transcendentalist Margaret Fuller. These were classes for women meant to compensate for their lack of access to higher education. Maria’s commitment to the anti-slavery movement convinced James to become involved — he ultimately became editor of the National Anti-Slavery Standard. She moved James toward a more liberal world view, out of his natural reserve, into such movements as Fuller’s and her Transcendentalism.

But what of her own poetry? Most was published shortly after her death, first by James privately, and only much later nationally. Amy Lowell, a Pulitzer Prize winning poet, and a relative of James, said “This is poetry! It is better than anything her husband ever wrote, and he always said she was a better poet than he.”

She appears in American Women Poets of the Nineteenth Century: An Anthology, edited by Cheryl Walker. Some of Maria’s poems were described there as “derivative, but others, such as ‘Africa’ and ‘An Opium Factory,’ were said to be impressive for their original imagery and fervency. Emily Dickinson was advised to read Maria’s poetry, which helped bring Maria more notice.

James Russell Lowell never lived in Watertown. The land the schools were built on was deeded to the town by Lowell as trustee of his wife’s estate, specifically to be used for a school building. James clearly believed that he would not have become the person and writer he was except for her influence, love and talents. Perhaps the school should therefore be named the “James and Maria Lowell School.”

Interesting. I went to the Hosmer School, in the building built in 1899! I always thought it was named after Harriet Hosmer!

What wonderful stories about three outstanding men who contributed so much formWatertown, I wish I had been told all about these scholars when I attended the Lowell,School.

This article is silent as to Harriet Hosmer’s lesbian sexuality, which is a vital element of her life, work, and legacy. Watertown should be as proud of her as she was of herself! See https://newenglandhistoricalsociety.com/harriet-hosmer-pioneering-woman-artist/ or Kate Culkin’s excellent biography, Harriet Hosmer: A Cultural Biography.

Thank you for bringing up this important aspect of Harriet Hosmer’s identity, and for the wonderful link and book rec!

Why not give history on Parker, Brown, Marshall Spring, Coolidge, Phillips and St. Patrick’s? I know they are closed but they still have a history that residents would find interesting.

My dad was born in Watertown and went to Browne Elementary. I am doing a life book for him and would also like to find the history on Browne Elementary. I’m trying to find a picture of the school for his book. If anyone has one I would be forever grateful if you could email to me at donna@stressawaymassage.com

My dad (Cliff Wallace ) was at Browne school from 1953-1960

Our “Wallace”ancestors immigrated to Watertown from Nova Scotia, Canada.

Thank you for any information.

Donna (Wallace) Chass

Reminder to sign comments with your full name.