By Bill McEvoy

In honor of National Nurses Week, local historian Bill McEvoy has compiled histories of some of the Civil War nurses who are buried at Mount Auburn Cemetery. This is part six of seven.

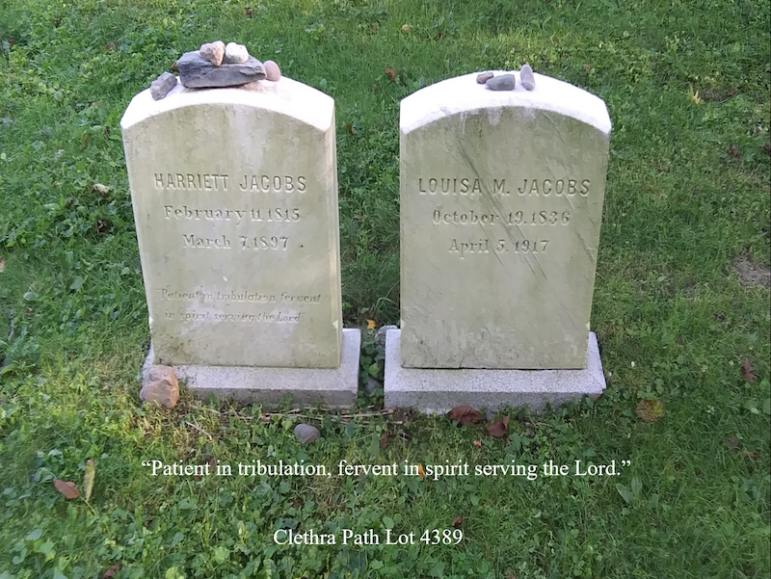

Harriet Ann Jacobs was born into slavery, on February 11, 1813, in Edenton, North Carolina. She died on March 7, 1897, in Washington, D.C. Raised in Edenton, Harriet, and her brother, John Jacobs were born to Delilah Horniblow and Elijah Knox, a carpenter. Harriet recalled a happy early childhood.

In her book, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, available as a free download on Google Books, she noted: We lived together in a comfortable home; and though we were all slaves, I was so fondly shielded that I never dreamed I was a piece of merchandise.

After Delilah Horniblow’s death, Harriet and John went to live with Delilah’s enslaver Margaret Horniblow. Harriet was only six at the time. Though it was illegal to do so, Margaret Horniblow taught her how to read and write.

Harriet wrote: for this privilege, which so rarely falls to the lot of a slave, I bless [Margaret’s] memory, Six years later, Harriet and John’s father, Elijah, died and was interred next to Delilah in a place known as Providence. Blacks in Edenton had purchased this tract of land communally and established a meetinghouse and graveyard there.

For African Americans in the area, Providence represented “their crowning effort to create their own space,” scholar Jean Fagan Yellin writes in Harriet Jacobs: A Life – 2004, available at most libraries.

That same year Margaret Horniblow passed away, and the ownership of Harriet and John were transferred to Horniblow’s three-year-old niece, Mary Matilda Norcom. But it was the child’s parents, Dr. James and Mary Norcom, who held ultimate power over the two siblings.

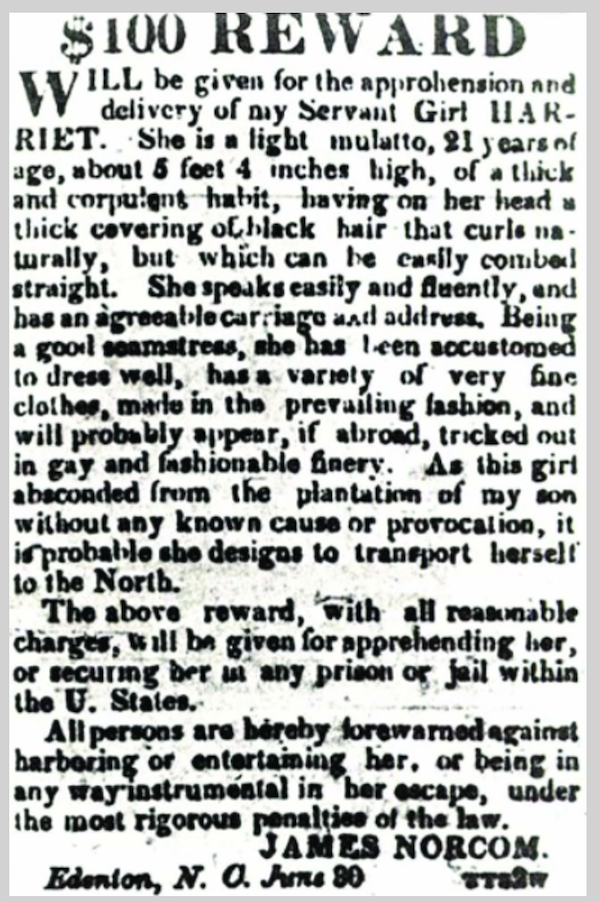

Dr. Norcom was a wealthy owner of a large plantation, and in his household, Harriet met the harsh indignities of slavery as he began a relentless campaign of sexual harassment.

Harriet, she wrote in her book, “My master began to whisper foul words in my ear. . .. I turned from him with disgust and hatred. But he was my master.”

Dr. Norcom denied Harriet’s request to marry a free Black man. In an effort to ward off his advances, she started an affair with Samuel Treadwell Sawyer.

A White man, Sawyer came from a family of colonial aristocracy, and practiced law in North Carolina. She gave birth to a son Joseph and daughter, Louisa, by Sawyer. She hoped Norcom “would revenge himself” by selling her.

Eventually, Harriet escaped to the house of her grandmother, where she sought refuge for seven years. Cramped in a tiny crawlspace nine feet long and seven feet wide, unable to stand, she endured the stifling heat of the summer and the bitter cold of the winter. With the light from a small hole, she passed the time sewing, writing, and reading, gaining a self-taught education that would soon serve her well.

Sawyer was eventually able to buy John, Louisa, and Joseph, and arranged for them to live with Harriet’s grandmother. Only through the small hole could Harriet gaze upon her beloved children.

When Sawyer later moved to Washington to serve in Congress, John accompanied him and in 1838, during a family trip to New York City, he escaped north. In Rochester, New York, he worked in the Anti-Slavery Office and Reading Room and lectured widely throughout New York and Massachusetts.

Sawyer arranged for Louisa Jacobs to live in Brooklyn, New York.

In 1842, Harriet’s family planned her own route north and, she was eventually reunited with her daughter. Later they moved to Boston where Joseph also joined the family. Harriet finally felt “as if I was beyond the reach of the bloodhounds; and for the first time during many years, I had … my children together with me.”

Much is known about Harriet involvement of the Freedmen’s’ movement, during, and after, the Civil War.

Although Harriet is not listed on the rolls as a Civil War nurse, I believe that the following articles, note her to be a “Civil War Nurse-in Fact.” She did double duty of nursing African American Soldiers, as well as escaped slaves.

The April 10, 1863, issue of the Liberator, published a full column letter from Harriet.

The white men of the north have helped us thus far, and we want to help them. We would like to fight for them if they would only treat us like men.

The colored people could not do enough for the first regiments that came here.

They had entire faith in them as the delivers of their race.

The sight of the U.S. uniform took all the fear out of their hearts and inspired them with hope and confidence.

Many of them freely fed the soldiers at their own tables and lodged them as comfortably as possible in their humble dwellings.

In return for their kindness and ever ready service they often receive insults and sometimes beatings and so they have learned to distrust those who wear the uniform of the US.

You know how warmly I have sympathized with the Northern Army: all the more does it grieve me to see many of them false to the principles of freedom.

But I am proud and happy to know that the black man is to strike a blow for liberty.

I am rejoiced that Colonel Shaw heads the Massachusetts regiment for I know he has a noble heart.

In the January 13, 1863, edition of the Liberator, Harriet wrote.

We have between 800 and 900, sick colored soldiers and more are expected daily…

All colored soldiers are well quartered; the medical attendance is good; but you know very sick men cannot eat hospital rations; and when they look up and say I have not eaten anything for two or three days could you bring me a little of so and so.

I think I could eat it — you wish by some magic your purse would lengthen you could give each poor boy what he craves. Their condition at least has bit little sunshine in it languishing and dying away from home in all they hold dear buried among strangers who neither sigh nor weep as the piles of earth falls on their coffin.

Yesterday I visited some men who were brought in several days ago nearly every one of them was suffering from lung disease. Such fearful coughing, I have never heard. It costs something to die for freedom.

North Carolina Nursing History, Appalachian State University, noted that

She escaped to the north and joined the abolitionist cause. During the Civil War, Jacobs nursed in Alexandria, VA for the Union Army and for the newly freed slaves living in the area.

Certain writings were also taken from:

M. R. Cordell, author of, Courageous Women of the Civil War: Soldiers, Spies, Medics, and More, it is noted on part 3, notes her as a Young Nurse, “First South;” Harriet Ann Jacobs: “She Did Her Own Thinking.”

Find the gravesites of the Civil War Nurses by entering their name here: https://www.remembermyjourney.com/Search/Cemetery/325/Map Bill McEvoy can be reached at billmcev@aol.com

Thank you for such interesting articles honoring nurses who served our country during the Civil War. It is a tribute to honor them and recognize their selfless service and care they provided the soldiers under their care. An appropriate way to honor them during National Nurses Week.

Thank you Bill McEvoy for your curiosity and research you have shared with your readers.

Agreed! This series has been so fascinating and informative. Much gratitude.