This article is part of a series on local history provided by the Historical Society of Watertown. It was written by Joyce Kelly, Board member of the Historical Society of Watertown. Joyce writes articles for the newsletter and is the newsletter editor. This was published in our July 2004 newsletter, “The Town Crier.”

THE TREATY OF WATERTOWN

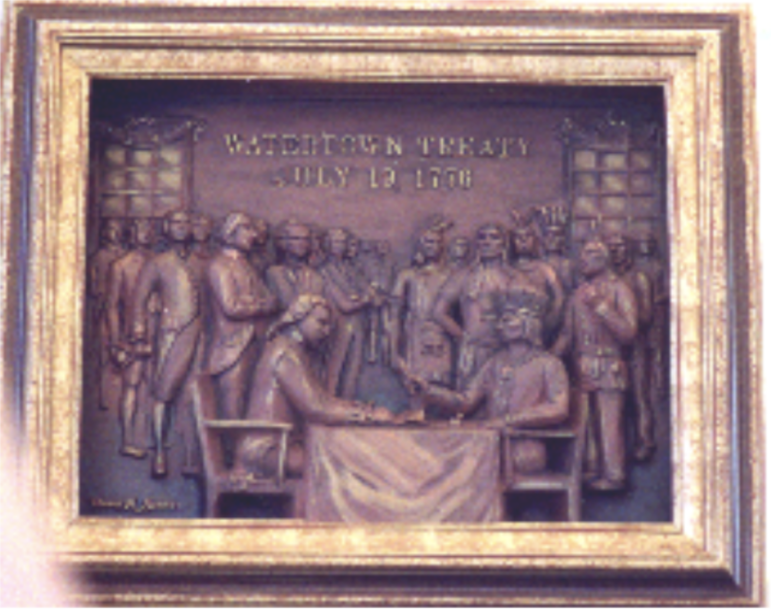

In July of 1996, The Historical Society of Watertown began celebrating Treaty Day. This observance commemorates a treaty of alliance and friendship signed between the Micmac Nation of northern New England and Canada, and the newly formed United States. It was the first treaty to recognize the United States as an independent nation. The treaty was signed on July 19th, 1776, a mere 15 days after the signing of the Declaration of Independence.

Many of our new members, and, perhaps, several of our not-so-long-standing members may not be familiar with the particulars of the signing of the Treaty of Watertown and the details leading

up to it. I wrote the following article for a brochure used for our 1999 Treaty Day celebration during Faire on the Square and thought it appropriate to acquaint our new members with the story.

The treaty was brought to our attention several years ago by Will Basque, a member of the MicMac Nation. Mr. Basque got in touch with Congressman Joseph Moakley to remind the people of Watertown of its existence.

During the Revolutionary War, General Washington was anxious to secure our northern border. In February 1776, he wrote a letter to the MicMac Grand Chief asking for his nation’s aid in the war against the British. A letter was also sent in October 1775 from the General Court of Massachusetts Bay. Seven Captains of the MicMac and three St. John’s (or Malecite) Captains responded and arrived in Watertown on July 10, 1776. Major Shaw “brought them in his sloop from Machias to Salem, from whence they rode hither in carriage which were provided for them.” They were asked to come in person, for not understanding each other’s language, it would be too difficult to communicate in writing.

The minutes of the negotiations and the signing of the agreement have recently been brought to light. The minutes report the “the Honorable James Bowdoin as President to the council, was directed to hold the conference with them.” The leaders identified themselves and their tribal affiliations, and told the council how many men they could supply to fight in the coming war.

President: What number of men is there in your several villages and let each confirm with respect to his own village only.

Ambrose Var: There are sixty men belonging to the St. Johns tribes. Joseph: There are sixty men belonging to my village, Winsor. Mattahu: In my village are eighty men. John Battis: In the village at Cumberland are forty men.

Peter Andre: There are fifty men at La Have.

Sabattis: At Gasper are fifty strong men.

President: Are there any more villages of Indians in Nova Scotia?

Indians: There are six more villages of Micmacs, but we do not know what number of men they have.

Council President James Bowdoin, perceiving that the visitors were tired and hungry, directed Major Shaw to provide them with “good lodgings and entertainment.” The meeting was adjourned until Friday, July 12th.

Since the guests spoke little or no English, Mr. John Prince was appointed as interpreter, assisted by Colonel Lithgow “who understands the Indian language.” Ambrose Var ( Editor’s Note: His name was Ambrose Bear, but the clerk wrote the name as “Var”) of the St. John’s tribe was chosen as spokesman for the Indians. He requested a few simple things, including “a truck house and a priest.” A truck house was a store where the Indians could trade their furs and skins for money, ammunition and provisions.

Ambrose reported that the British had violated a treaty with them, and that they no longer trusted a Mr. Anderson, who claimed to represent the governor of Halifax, Nova Scotia. He reported that Anderson had tried to bribe them with money, and a sword and pistol, which Ambrose then presented to the Council. Council President Bowdoin then asked about their consideration of entering into a treaty with the colonists.

President: What is the disposition of the Micmac and St. John’s Tribes in general? Would they all enter heartily and with resolution into the war on our side?

Indians: Both the Micmac or Cape Sable Indians, and the St. John’s Indians are all for helping Boston. We know their hearts for we had a talk with them.

The President then delivered a speech to them. Excerpts are as follows:

President: You have heard that the English people beyond the great water have taken up the hatchet and made war against the English United Colonies in America. We once looked upon them as our brothers, as children of the same family with our selves, and not only loved them as brothers, but loved and respected them as our elder brother. But they have grown old and covetous. Many of their great men have wasted and squandered not only their own money, but the money of the public; and because they cannot obtain in their own country a sufficiency to support their excessive luxury, and satiate their desire they want to take from us our money and our lands for their purposes. And at the same time to deprive us of our liberties and make us slaves. They have already taken away a great deal of our money, and many of our privileges, and we have borne it with patience, having only told them that their doing it was unbrotherly and unkind, and most earnestly prayed them again and again to desist from their unfriendly and cruel treatment of us. But all our petitions have been disregarded. And they have trodden them as waste paper under their feet. After this ill usage, and repeated insults, we have refused to part with any more of our money and privileges and this refusal has brought upon us the war in which we are engaged. Our enemies, before they openly declared themselves to be such, were received as friendly and admitted them into our towns and sea ports, taking advantage of this peaceable disposition of ours. They sent troops and ships and took possession of Boston, and strongly fortified it, expecting we should permit them to do the same with other places, till they had secured the whole country. But they found themselves mistaken. For when a large body of them went from Boston secretly by night into our country, in the month of April last year, and killed some of our people, burnt or damaged many of their homes, stole and destroyed much of their property and committed other acts of cruelty, a number of our warriors assembled and drove them back and killed a great many of them. (This is in reference to the Battle of Lexington and Concord.) And a little while after, killed a greater number of them at Charlestown, with comparatively little loss of lives on our side, the war being thus began. (This is in reference to the Battle of Bunker Hill.)

We have given you this information that you might know the true state of things, and we would inform you further that as we and the St. John’s and Micmac Tribes of Indians are countrymen and not very distant from each other, we ought to be and it is our interest to be mutual friends and as brothers and we are glad to find by what you have now said, that you are of the same mind. Accordingly, we, the Governor of the Colony of Massachusetts Bay, in behalf of the Colony and of all the Colonies in North America, receive you to our friendship. Your acceptance of it entitles you to be considered by us as brothers, and your enemies over shall deem our enemies, and will do all in our power to protect you from them. We do not, however, ask you to join with us in the war unless it is your free choice to do so…

When you have considered what we have now said, and are ready to give an answer to it, we will hear you.

After a brief recess, the meeting resumed that same day at three o’clock. Ambrose Var addressed the Council.

Ambrose: We have the same to say today that we said yesterday, that we are your friends and brothers, and will join in the war on your side. You may depend upon it that we will not break our words. We will allow all that are here present hear us and the God of Heaven hear us, and we will engage in the war, for we are brothers. We would not lie to save our right hands. We pledge our faith that we will do what we promise. We love Boston. It gives us a great deal of concern they were so ill used. We should have been glad to have had the arms of Boston to keep. If we had had the Boston arms, we should have been able to defend ourselves. In case the people of England should come to drive us out of our country, we will give you the information of it immediately. We shall be very glad to have proper goods for our furs and skins, and we want them up St. John’s River.

We are not capable of writing. We cannot convey our mind as we would wish to do. We will pledge our right hands in faith of what we have promised. There are some of us here that are willing to go to war now and would go to General Washington immediately.

Upon this three of them went from their seats into the broad aisle and manifested a great desire to go.

It was decided that the visitors would return to their homeland and call their men together to

see how many would be willing to join General Washington. Council President Bowdoin requested that each man bring his own gun, for which they would be paid a dollar. Ambrose said that the tribes would do all they could to help the colonists, but some of their men would be obliged to stay behind, keeping their guns, to protect their villages. The meeting was then adjourned until Tuesday, July 16th.

President Bowdoin then asked what provisions the guests wanted delivered to the truck house in Machias, Maine.

Ambrose: We want shrouds and blankets for winter and summer. Our children and families are always in want of these articles. We want powder, shot, flints, knives, combs, hatchets, small axes of two different sizes, paint, some steel traps to catch beaver, and we want guns too to go a hunting with.

President: Major Shaw has delivered us a memorandum for a number of articles. We will order our commissary to supply the truck house with them if they can be procured.

President Bowdoin reported that he had received a letter from General Washington, asking the Indians to provide five or six hundred men, perhaps some coming from their neighboring tribes. He asked for their immediate service, not to exceed two or three years. They would be paid the same wages as the colonists for their service.

Ambrose agreed to speak with members of the other tribes. Arrangements would be made for their return home, and eventual return to Boston to go on to join General Washington. President Bowdoin had received an announcement of the signing of the Declaration of Independence. It was read and interpreted during this meeting, declaring the colony’s separation from the British.

President: These Colonies have lately, by their great Council at Philadelphia, declared themselves free and independent states, by the name of the United States of America. The certain news of it and the Declaration itself are just come to us and we are glad of this opportunity to inform you, our brothers, of it. This said Great Council,…do in the name and by the authority of the good people of these Colonies, solemnly publish and declare that these United Colonies are and of right ought to be free and independent states; that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain, is and ought to be totally dissolved, and that as free and independent states, they have full power to levy war, conclude peace, contract alliances, establish commerce, and to do all other acts and things which independent states may of right do…they mutually pledge to each other their lives, their fortunes and their sacred honor.

Next, the new treaty was read by Benjamin Greenleaf Esq. and interpreted to the MicMac and St. John’s tribes. They conveyed their agreement with the conditions and said they were ready to sign it. “After mutual healths were drank, the conference was adjourned until the next day.”

In 1998, the Historical Society of Watertown arranged for the restoration of The Treaty of Watertown. It resides in the Massachusetts State Archives on Morrissey Boulevard along with the minutes that were excerpted in this article.

I am very impressed by your publication and wish to be placed on your mailing list.

I am a descendant of the 1634-1733 Whitney’s who owned several properties in the westerly section of Watertown, Mass. I have a copy of a map of their holdings. (John Whitney, W.H. Whitney of Boston, Capt. Daniel Whitney, Benjamin Whitney) and wish further information on the Whitneys of that era and properties owned.

Thank You,

Michael J Whitney

Show Low, AZ