The name of Charles Lenox, an African-American man from Watertown who fought in the Civil War, has become more well known this fall after his life was the focus of New Rep Theatre’s first Moving Play.

Lenox served in the famous 54th Massachusetts Infantry. In the play, the same streets on which Lenox lived his life were used as the stage. (Read more about the play here).

Bob Bloomberg, of the Historical Society of Watertown, wrote a detailed piece about Lenox’s life for the The Town Crier, the Historical Society’s newsletter, and he gave permission for the piece to be reprinted in the Watertown News.

Here is Bloomberg’s Piece from The Town Crier:

The following article was written by Historical Society Board Member Bob Bloomberg. Bob has recently been appointed to the Board of the Watertown Historic District Commission. Bob is a former Board Member of the Quincy Historical Society. He is also a genealogist and has written several book reviews and newspaper articles.

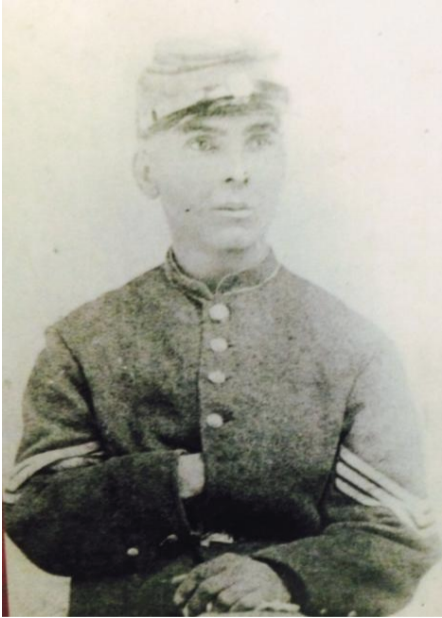

Many Watertown citizens served during the Civil War, but only one fought in the ranks of the famed 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry. This was a “special corps,” composed of “persons of African descent.” Charles William Lenox enlisted at the age of 38 as a Corporal in the 54th in February 1863, barely a month after it was formed. He served valiantly at several major battles of the War, including the assault on Fort Wagner and the attack on James Island, where he carried the national flag, and the battle of Honey Hill, all in South Carolina. Luis Emilio, an officer in the Regiment, wrote an eyewitness history of the unit entitled A Brave Black Regiment: The History of the 54th Massachusetts 1863-1865. He quoted Lenox who described the Honey Hill battle in vivid terms. Lenox saw horses struck by shells, an ammunition wagon blown up, and cannons disabled. What struck Lenox most forcefully was the musketry, which was worse than at Fort Wagner, and the so- called Rebel yell, which “was more prominent than I ever heard it.”

Over the course of his 2 1⁄2 years of service, according to Mary Livermore, in her book, My Story of the War, Lenox carried the flag with bravery and devotion. She wrote that he was hit by spent musket balls, and had his clothing torn by flying shots. Another account related that once, when the 54th was surrounded, Lenox wrapped the flag around his body and lay in a ditch with the dead until nightfall when he could make his way back to the Union lines.

While Lenox’s exploits during the War were exciting and important, there is another area that deserves telling for its historical importance. The story of Lenox and his family offers a glimpse into one hundred years of the middle-class experience of free persons of color in Massachusetts.

Lenox was the grandson of Cornelius Lenox and Susannah Toney (or Tory). Cornelius was a soldier in the Revolutionary War. At his discharge in 1781, he was under the command of a Sgt. Richards of Watertown. This may explain why, sometime before the 1790 U.S. Census, the couple moved from Boston to a home and two acres of land that straddled the Newton/Watertown line (on what is now Watertown St.). He was a property owner and taxpayer in Newton throughout the 1790s and well into the early 1800s. He was a man of some means as evidenced in the Watertown Records of 1808, were he was paid $63.50 for the support of Jude Francis’s child (apparently, he boarded the child at his home for several months), and for “the trouble of attending the funeral.”

Cornelius and Susannah’s daughter Nancy married John Remond of Salem. John Remond’s son, Charles Lenox Remond (Charles Lenox’s first cousin) was a famous abolitionist speaker. Remond’s family were prominent Black residents of Salem, and were, like the Lenox family, also in the hairdressing (barbering) and catering businesses. In 1838, the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society chose Remond as one of its agents. As a delegate from the American Anti-Slavery Society, in 1840 he traveled with William Lloyd Garrison to the World’s Anti-Slavery Convention in London. Remond gained a reputation as an eloquent lecturer and is reported to have been the first black public speaker on abolition. This close relationship of kinship, occupation and interests undoubtedly influenced Charles’s life in virtually every area.

In the book Women’s Rights and Transatlantic Antislavery in the Era of Emancipation, by Kathryn Sklar and James Stewart, Cornelius is described as the head of a very large free black family of moderate but stable comfort. He ensured that all his children were educated in trades customary for blacks at the time — hairdressers (barbers) for the men; catering for the women. He expected that they would join him in his salon.

So, it was natural for Cornelius’s son John to be apprenticed at the age of 14 for seven years to a hairdresser in Salem, MA, where he learned the trade. After completing his apprenticeship, John returned to Watertown in 1815, opening up a shop near the old Spring Hotel on Main St. in Watertown Square. Two years later he married Sibel Dickerson of Salem. It is sometimes difficult to determine John’s exact place of business because there were then no street numbers. Often, a residence or business was said to be located “near” another street, building or business, or simply, on “Main.”

Prior to 1841, John moved the business to a wooden building on what became the site of the Town Hall. That building burned down in 1841, and he built a new shop next to Woodward’s Drug Store. In 1868 it was moved across Main St. to the corner of Church St, where it stood in 1881. Charles’s last location was in the Whitney Block on Main St.

Charles William Lenox was born in Watertown on November 2, 1824. He attended Watertown Public Schools. His Civil War enlistment papers in 1863 show that he was 5’5” tall, with a light complexion, and with grey hair and eyes. When Charles returned from the War, he resumed his place in his father’s shop. Their business prospered, as evidenced by the 1865 Massachusetts Census. Living with them was Susan Kelton, a 70-year-old white housekeeper.

The U.S. Censuses from 1860 through 1880 list Charles, his sister Louisa, and their father John living together. John had substantial real and personal property. His real estate was valued at $2,000, and his personal estate was valued at $1,200.

In each of these census reports, the family was listed as “mulatto.” At the time, and in a general sense, this term meant anyone who was of mixed white and non-white descent. But the census further defined the term as anyone who was of 3/8 to 5/8 non-white descent. Charles’s grandfather Cornelius was listed in Forgotten Patriots, African American and American Indian Patriots in the Revolutionary War, (where he was in the Woburn militia) edited by Eric Grundset, as a mulatto. Nevertheless, it was clear that Charles was seen by others as Black, and more importantly, identified as Black by enlisting in the 54th Regiment.

The milieu in which Charles lived and earned his living was virtually all white. In 1850, there were two blacks in Watertown and in 1860 there were three—these were John, Charles and Louisa. Even in 1870 the number had increased to only fifteen. The total town population grew from about 2,800 to about 4,300. There were three hairdresser shops in the town listed in the first town directory of 1867-68, of which John and Charles’s was one. Twenty years later there were five. John and Charles’s customers were overwhelmingly white. The fact that the shop was open from 1815 until Charles’s death in 1896 is a testament to both the ability of John and Charles to transcend racial barriers, and to the willingness of Watertown residents to do the same.

Charles became, if not wealthy, then certainly well off. In 1871 Charles had a savings account of over $1,000 at the Suffolk Savings Bank for Seamen and Others in Boston. At that time his shop was on Main St., opposite Church St., probably at the site of the Watertown Savings Bank building.

By the 1880s, John had retired from the business, coming to the shop to each day to chat with the customers. He died in 1887, and is buried at the Common Street Cemetery in Watertown. Charles kept the business going at the Whitney Block on Main St. He lived in a house on Main St. at the corner of Church Lane until very shortly before his death.

Lenox had been a loyal and active member of Watertown’s Isaac B. Patton GAR (Grand Army of the Republic) Post 81, and a long-time member of the First Parish Church in Watertown. He was a registered voter in Watertown in 1884. He gifted a book to the New England Genealogical and Historical Society’s library in 1888.

Other than these affiliations and activities, there is very little information on Charles from after the War until the late 1880s. Then, perhaps wishing to rekindle old memories and friendships, he began to attend abolitionist and Civil War related events. The Boston Globe reported on a meeting of “Colored Veterans” in August of 1887 in Boston. Lenox was present, wearing “the same cap, blouse and canteen that he wore on his return from the war.” He also wore the color belt which was used in the assault on Fort Wagner in 1863, and in which Color Sergeant Lenox carried the flag. Earlier, in June, the Globe had reported that Lenox was a member of the Executive Committee from Massachusetts that organized the event.

In 1893 he and his brother John attended an anti-slavery reunion in Danvers, Mass. That same year Charles was one of the “prominent people” who was at the funeral of General Benjamin Butler. Butler had helped create the legal idea of effectively freeing fugitive slaves by designating them as contraband of war in service of military objectives. As Chairman of the US House Committee on Reconstruction, Butler authored the Ku Klux Klan Act of 1871 and coauthored the Civil Rights Act of 1875. Butler was also Governor of Massachusetts from 1883 to 1884.

In 1896 Charles attended a lecture given by Frederick Douglas on Douglas’s views on the “Negro Problem.” On the platform with Lenox were many of the old abolitionists, including William Lloyd Garrison, Robert Treat Paine, and Samuel May.

Charles died from dysentery on August 9, 1896. He had never married. His death was reported in the Boston papers as well as Watertown’s. Three weeks before he died he was compelled to leave his home of fifty years because of its “dangerous condition.” According to one obituary, he was very attached to the place, and this may have hastened his death. Services were held at the First Parish Church.

His body was escorted to his grave at the Common Street Cemetery by members of the GAR Post, and he was buried in accordance with GAR ritual. Taps was played. Flags in town were at half mast, and many shops in town were closed the afternoon of the funeral.

General Morris Schaff, a veteran of the Civil War, spoke fondly of Lenox. He related a conversation that he had recently had with Lenox. Schaff asked Lenox if he had a pension. Despite his bravery and close calls with death, Lenox replied that he had refused his pension, saying that since he had not been injured and was not sick, he was therefore not entitled to one. Lenox recalled with clarity events of fifty year prior, when there was only one church in town, and Blacks were required to sit in the gallery. Schaff concluded: “He was a gentleman in every sense of the word, modest and unassuming, but with a fund of knowledge of times gone by equalled [sic] by few.”

The pastor of the church, Reverend William H. Savage, gave the eulogy. Savage said that the foundation of Lenox’s life was honesty. He too noted Lenox’s knowledge of Watertown’s events. Lenox was “a gentleman, gentle in temper, gentle in his thoughts about the world and his fellow men. He was a brave man in a great hour of trouble. He was a citizen soldier.” Even a decade after his death, he was highly thought of. In Watertown’s Military History, published in 1907, Lenox was described as a “well known and respected citizen…”

The play was well-written and acted. I thoroughly enjoyed it.