The new home of a Watertown day care center will be in a building off Galen Street that’s full of history, from the architecture to the former uses, which includes being a cookie factory to a printer of textbooks and one of the nation’s largest providers of checks.

First Path Day Care Center moved to 13 Boyd St. in November after many years sharing the Watertown Boys & Girls Club facility. When First Path learned it would need to find another location, the search led them to purchase the building on the Southside of Watertown in 2017. First Path General Manager Max Bolyasnyy noticed something special about the building.

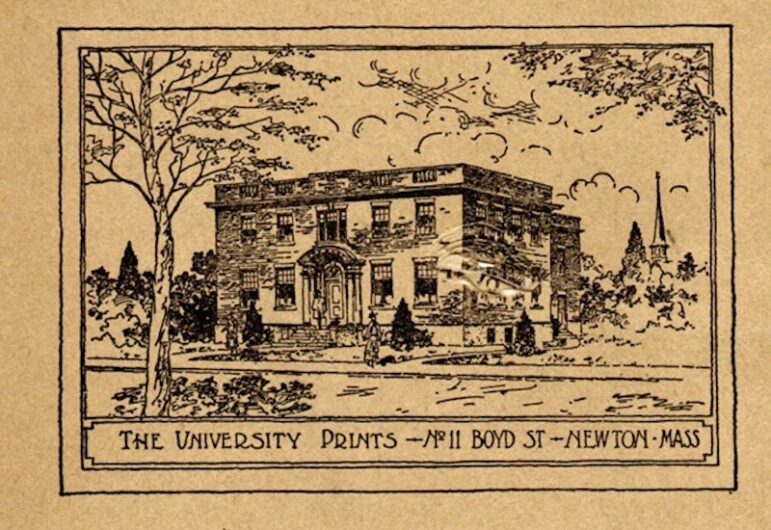

“The first time when we visited the building we were told that it used to be a cookie factory. I kind of wondered, ‘Well, a cookie factory, this is strange.’ And when I came out outside, I saw on top of the building — University Prints — and I got curious, ‘What is University Prints?'” Bolyasnyy said.

He did some research and discovered that University Prints was founded by Harry Huntington “H.H.” Powers and his wife, Mary Manta Powers.

“H.H. Powers was a professor at Cornell University. This was his last position, but he also taught in a number of colleges and schools, and he also was a prominent writer,” Bolyasnyy said. “He was an economist. He was also teaching sciences. He also spoke many, many languages, and he was interested in history, arts and culture. He traveled all around the world.”

Powers, who lived from 1859 to 1936, published books on a variety of subjects, including arts and architecture, as well as history. His books can still be found for sale online.

Bolyasnyy found that Powers moved to the Boston area in 1910 and he and his wife had the building on Boyd Street constructed.

He also started the Bureau of University Travel, which ran tours and courses for college students, graduates and teachers from institutions of higher learning. The Bureau was run out of the building on Boyd Street.

The University Press building was designed by prominent Boston architects, Brainerd and Leeds, according to a letter from the Massachusetts Historical Commission that recommended that the building be eligible for the National Register of Historic Places.

After learning about the building’s history, the leadership of First Path wanted to preserve it.

“If we did not buy it, it would probably go to the hands of a developer who would either demolish it or completely change it,” Bolyasnyy said

After Powers died in 1936, the building went to his son. Bolyasnyy believes his son sold the building in 1946.

“University Prints still continued operating in there, but I’m not sure if it was under the same ownership or not. I believe probably ownership would have changed,” he said. “Probably they sold the building and ownership. So the company which purchased it was in cookie manufacturing. It was a team of women, two women, who bought it and they basically started doing that in the building.”

In 1955, Bolyasnyy said, a new owner of the building, Hartshorn Associates (who purchased it in 1949 from the original owners) rented part of the back of the building to Helen Cross Bakery. The company prepared and packaged frozen cookie mix.

While First Path did not find any evidence of a cookie mix company they found printing equipment, and a big safe with the name Garden City Press on it.

“So everybody who comes here, the first thing they do, everybody, they want to see if actually it has money (inside). Without an exception — everybody,” he said. “I mean, to be honest, I got a little bit curious, myself. But of course, as they try to open up and well, there isn’t any money, not a single penny.”

Garden City Press relocated to the University Prints Building after being located at the current site of One Newton Place (the curved building near the Mass Pike exit) in the 1920s, Bolyasnyy said.

“I was told it was one of the largest printers in the country for checks,” Bolyasnyy said. “But then computers came along and, well, basically it became antiquated.”

In 1962 the building was acquired by Russell Wennberg, who founded Barn Family Shoe Store in Newton in 1948, Bolyasnyy said. The shoe store is still in business in Newton on Walnut Street. The check printing operation was run by Peter Young, who had purchased the building in 1978, he added, and First Path purchased the building from Young’s family.

Some evidence of the age of the University Prints building can still be seen.

“I was amazed by how well it’s preserved inside and outside, up to the little, tiny details, hardware doors, everything, pretty much the way it was 100 years ago when H.H. Powers would come in here,” he said.

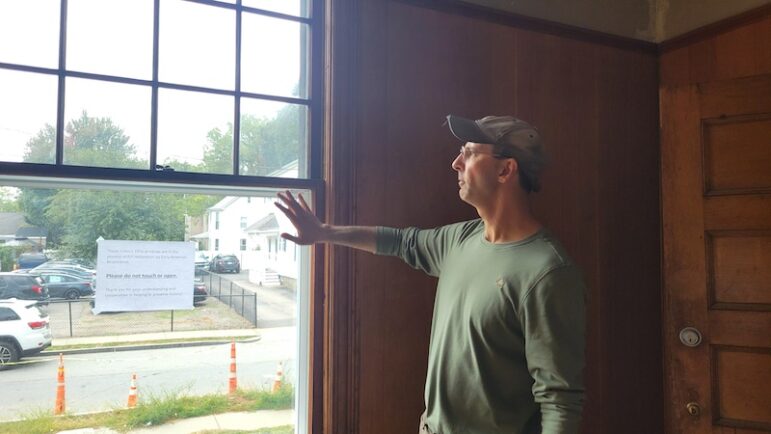

Where possible, when renovating the building, the current owners have tried to preserve or replicate the historic parts of the building. When working on the building, there was talk of replacing the windows with modern ones, but Bolyasnyy preferred the old ones.

“They said, you cannot fix this, it’s not going to be energy efficient. I said, ‘You know what? Don’t change anything.'” Bolyasnyy said. “And this is how I started finding out I love it, actually. These historical windows can be restored professionally by professional restorers. It can be actually made as efficient as brand new windows.”

The building also includes a residential section with apartments accessed by an interior stairway. The stairway is lit by a large skylight, but a section of the glass was damaged.

“We couldn’t find a replacement glass. And the restorer says, ‘Well, Max, I think I have to replace it ] with new, as well,’ Bolyasnyy said. “I said, “Can you do something?” And he says, ‘Well, Max, I know it hurts. Let me, let me see.’ He looked, searched, searched, searched, and finally, he found some reclaimed glass in Pennsylvania that was almost identical. He saw samples, then he basically took a piece of paper, made the shapes, sent it, they cut it. Identical. The same period, the same everything.”

Members of the Historical Society of Watertown toured the building with Bolyasnyy. Joining the tour was Historical Society board member Marilynne Roach.

“I was impressed by Max’s appreciation of history and of Watertown history in particular even though he didn’t grow up here,” she said. “And that the original large windows that provide such good light were not trashed (as the vinyl replacement window salesmen recommended) but rather repaired to continue their useful life.”

Other evidence of the historic use of the building is a large industrial elevator. On the outside the elevator has a fire door made by Coburn of Holyoke, Mass. Bolyasnyy would like to turn it back into an elevator.

“The (elevator) platform was removed by the people who owned it before, but otherwise it’s all originals there. And of course, this was made for this building, for the central printing operation,” he said. “And we will be installing a new lift, a handicap lift. So reusing the shaft that has been already modified, yeah, but in order to comply with all the regulations, we are literally missing about an inch (of clearance). … Because of that, this has to be removed completely. Once removed, it’s going to be gone. And there are only a few examples of these doors remaining, surviving and this is one of them.”

First Path has submitted a request for a variance from the State to allow them to use it as a handicap elevator.

The Watertown Historical Commission held a pair of meetings the building on Boyd Street, and determined that the elevator doors have historical significance, Bolyasnyy said.

“I am grateful to the Watertown Historic Commission, its chairman Elise Loukas, the staff members Larry Fields and Susan Jenness for their time and efforts in helping preserve this important piece of Watertown’s history,” he said.

First Path also needs to file a form from the Watertown Commission on Disability.

“The Commission on Disability already provided feedback that one inch is not going to be an issue, but we need this to be on a form and maybe some additional feedback,” he said. “And once this is provided, and we know it’s really not going to be an issue.”

In December, when looking into the application process, Bolyasnyy found that the application will also have to be submitted to the Massachusetts Historical Commission for review, before MAAB hears the matter.

“It is a lengthy and complicated process,” Bolyasnyy said.

The area where First Path is running the day care facility has been returned to how it looked in the past.

“The ceilings were raised to original height, the original office area was preserved and converted to our infant room. We preserved original 6-foot-high windows. We went with natural wood flooring which is consistent with the original design,” Bolyasnyy said.

Though First Path is the official owner of 13 Boyd St., Bolyasnyy said he doesn’t see it that way.

“We don’t own the building. We’re just caretakers, in a sense, because this building is going to be here for generations and generations,” he said. “So, whoever it was, the next generation, and you know, they could come in and see how things were, maybe in 100 years from now, they will come in and say, ‘Wow, this is where things were 200 years ago.’ Because, you know, the further you go away, the more amazing things get, right?”

WHAT MAKES A LANDMARK?

What do we mean when we designate something a landmark? It’s a tricky question as advocates of preserving the 100-year-old storefronts at 104 and 106 Main Street found out. Landmark laws were enacted to preserve things “we the people” deem culturally significant. Sadly, they don’t always protect what we actually want to save. When government officials, historians, and preservationists talk about landmarks, they usually mean sites of architectural or historical distinction or places like the Grand Canyon. When ordinary people talk about things that define communities and neighborhoods, which they fear losing and hope to keep, they’re thinking not only about the Boston Public Library and Faneuil Hall, but a beloved cafe, farmers’ market, or local high school, or even a tradition like Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade. There is often a disconnect between what many people want to preserve and what official permission granting authorities deem significant. But how do we treat less obvious or tangible things and values such as the physical fabric of a community or a sense of place? UNESCO, the United Nations cultural organization, more than twenty years ago established global lists of intangible cultural heritage, which the organization defines as “practices, representations, expressions, knowledge skills — as well as the instruments, objects, artifacts and cultural spaces associated therewith — that communities, groups, and in some cases, individuals, recognize as part of their cultural heritage.” That means intangible heritage need not be a building or place, making intangible heritage the next frontier for preservation in America and at the local level. Obviously, intangible heritage may be difficult to legally define, but depending on their neighborhood or municipality, residents have a pretty good sense of what it means. Many residents might say it is more important to preserve the Main Street storefronts, which Watertown did nothing to protect, than to designate as a landmark, yet another classic edifice by a well-known architect. Yes, I’m generously stretching the term intangible heritage. Determining what is intangible heritage requires addressing issues outside the purview of existing landmark laws, issues that pose questions about what makes a healthy neighborhood and vibrant municipality. It’s time for thinking that goes beyond whether a site is architecturally significant and toward thinking about collective priorities. Who benefits from preservation? Are there built-in biases in how landmark status is determined? The idea of saving an important neighborhood business raises a lot of red flags. For example, should a family-run business like Fresca’s receive special preservation treatment if, say, it were sold to a franchise chain? Does it matter if the owners change, or if the character of the place changes but its function doesn’t? In the end, all these hard questions about intangible heritage, or whatever you choose to call it, come down to how we want to define and preserve our neighborhoods, out culture, and ourselves. There are no easy answers, but the discussion itself should be part of the preservation process.

I apologize for wrongly referring to Tresca’s as “Fresca’s.” Auto-correct can be a real nuisance.

Since it’s a day care facility, will all lead paint be removed? Are they removing any lead water pipes? Are they checking for mold? Are they removing all mold? Is there asbestos? Is that being removed? Will these old windows break into dangerous chunks if broken? Are they checking for heavy metals and dangerous chemicals, since this building was used for industrial purposes? Sure, old buildings are beautiful, but safety for our current and future children and employees needs to be the top priority. It’s wrong to preserve the past without preserving our future.

Reminder that comments must be signed with your full name.

Wow, I’m usually a pretty careful person, but I don’t understand why anyone would question the extremely detailed inspection process that the state has for approving daycare sites… There’s a 62 page handbook of requirements with all sorts of health and safety issues, square footage per child, teacher/student ratios place space, food and drink preparation, supervision etc.

This is in addition to mitigating all any and all lead paint, safety hazards, etc., etc.

Suffice it to say that the state is in charge of more items than you can imagine in the building and that first path has certainly complied with everything and then some!!

Also, fortunately, with a 26 year history, they are actually one of the local Watertown experts on complying with state requirements and even exceeding them!

Carolyn,

As usual, you ask the right questions, and your observations are spot on!

And kudos to Mr. Bolyasnyy for his foresight and attention to detail in caring about Watertown’s historical architecture as well as Watertown’s children. It is quite impressive!