The following story was is part of a series on local history provided by the Historical Society of Watertown. It written by Sigrid Reddy Watson Terman for the July 2002 Historical Society newsletter, “The Town Crier”. Sigrid is a former Board member and former President of the Historical Society, as well at a former Director of the Watertown Free Public Library.

For several years starting in 1997, she wrote a Watertown history column for the Watertown TAB/Press called “Echoes.” Sigrid published her columns in a book called “Watertown Echoes: A Look Back at Life in a Massachusetts Town”. The book is available for purchase through the Historical Society of Watertown for $10.00. To purchase it, please contact Joyce at joycekel@aol.com.

EMMA NEIBERG TAYLOR REMEMBERS WATERTOWN’S JEWISH COMMUNITY

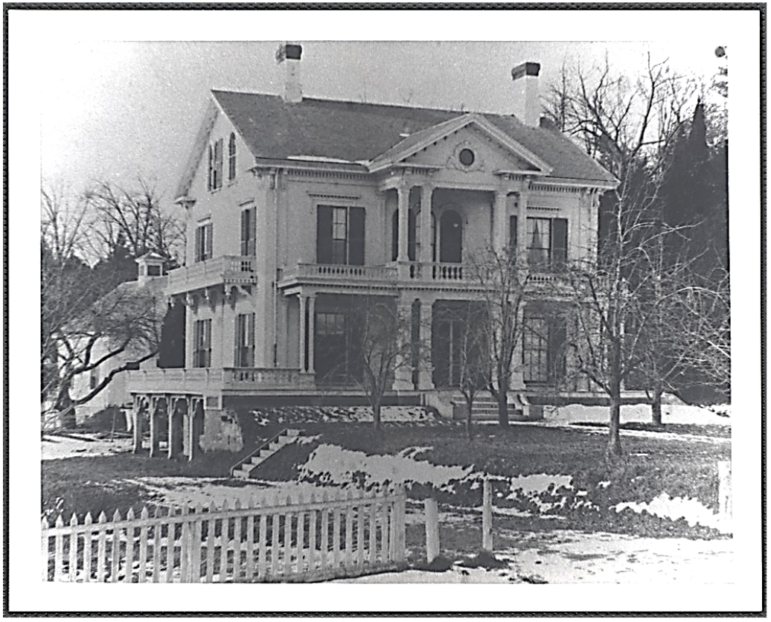

Emma Neiberg Taylor, who now lives at the Marshall Home, is in her ninety-second year. She was born at 9 Mt. Auburn Street in 1910, and has lived in Watertown all her life. To capture her memories was not difficult, for her mind is clear on the events of what most of us consider the remote past.

When Emma Neiberg’s parents moved to Watertown in 1900, Watertown was still a country town. Jacob, her father, had emigrated to Boston from Russia, and it was in Boston that he met his wife, Rebecca Needel, whose family had also come from Russia. As a young woman Rebecca worked in a factory that made men’s hats, and according to her daughter, had met her future husband only once before they married, for the union had been arranged by their families.

Jacob Neiberg and his friend, Benjamin Katz, of Myrtle Street, were both engaged in the junk business. When one half of a duplex house around the corner on Arsenal Street became available, Jacob moved his family into it, for on the property there were two big barns, which, as Emma says, were convenient for sorting the junk that her father picked up in his forays around town, and had space for his horse and cart. The junk consisted of newspapers, tin cans, old clothes, bottles, rags – anything that people wanted to dispose of in those days, with the exception, of course, of garbage, which went to a pig farm. The discarded clothes could often be sold, and the rags were useful in the paper-making business, for paper with rag content was superior for stationery.

In the early part of the 20th century, when Watertown was still a country town, it was difficult for Orthodox Jews to buy the kosher foods that they needed for the observance of dietary laws, and so once a week someone in the community would travel to Boston to buy meat and groceries for several families. Later on, Emma says, a butcher with a horse and wagon would visit Watertown on Thursdays to deliver kosher foods which the housewives could then prepare in time for the start of Sabbath observance at sundown on Friday.

Attendance at synagogue was a problem for the Neibergs, the Cohens, the Katzes, the Shicks, the Perlmutters, and the half-dozen or so other Jewish families, who, according to Emma,

lived in Watertown at that time. In the early years the Neibergs held High Holy Day services in their own home for the families in the Watertown Jewish community. Later they met for services at the Strand, the old movie theatre on Galen Street. The Perlmutters ran a clothing store on Watertown Street in Newton, and their son, Sam, who became a physician, remembered attending Sabbath services there. As time went on a number of families in Newton and Watertown organized Congregation Agudas Achim, an Orthodox synagogue on Adams Street in Nonantum. Emma says that on every Sabbath her father would put his yarmulke in his pocket and walk over to Newton to attend services. The synagogue on Adams Street is on the National Register of Historic Places and was recently carefully restored, for it is one of the earliest in the area. It is still attended by Jews in Newton and Watertown.

The Shick family, who at that time ran the Watertown Dairy Farm on Grove Street on property they had purchased from the Simon Stone family, lived on Arlington Street. As a temporary measure – for it was essential for them to be able to walk to temple on the Sabbath – they met, with their neighbors, for services in the East End fire station. Eventually they found a more permanent location in a building at the corner of Lexington and Belmont Streets. They founded a Jewish community center which over the years evolved into the Beth-El Temple on Concord Avenue in Belmont. Like the early settlers of Watertown, who kept moving the location of their meeting house as the population expanded westward, the Jews of turn-of-the-century Watertown relocated their place of worship as their community grew. Orthodox Jews, required to get to temple on foot, needed it to be within walking distance.

The Shickshad one daughter, Bessie, who became Emma Neiberg’s best friend, although Bessie was two years older. Other members of the Jewish community were the Rosoffs, who lived on Arlington Street at the corner of Belmont Street. The Rosoffs founded the Rosoff’s Pickle Company on Bigelow Avenue in the East End.

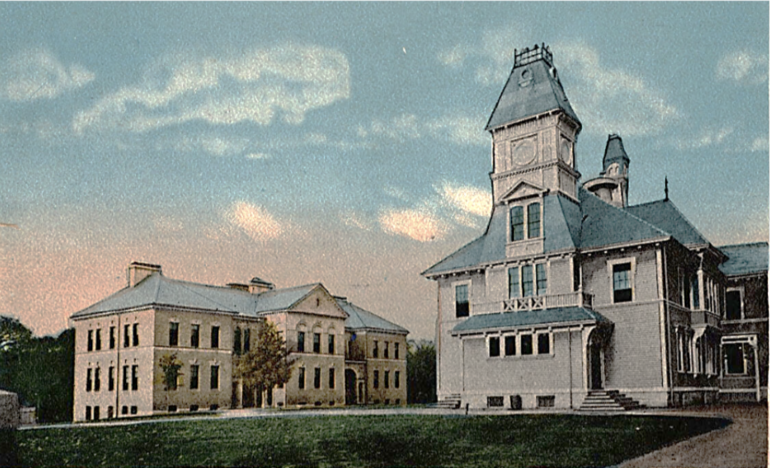

Emma says that she attended practically all the schools then in Watertown, many of which no longer stand. She said she went to the Frances School, the Grant School, the Phillips, and the Parker School on Watertown Street on the South Side. To visit her friend Bessie Shick, Emma took the trolley up Arsenal Street to Grove Street; the two girls would then meet on Arlington Street, near the old cemetery, to go to the movies at the Coolidge Theatre in East Watertown Afterwards, Emma would take the five-cent car ride home.

Emma was the third child in her family, and was, she says, three years old when the family moved to the duplex house on Arsenal Street near the end of Taylor Street. She said that families in those days depended on each other for help in time of need. When the people in the other half of the house wanted to attract her family’s attention, or vice versa, they would rap on the wall of a closet on one side that could be heard on the other side. One day when Emma came home from school she found her mother lying on the kitchen floor, with blood all around her. Frightened, she ran to get the next-door neighbor, who, she said, was “a black woman, Mrs. Whitman, who told me to go into the dining room and wait until she called me; she said she would take care of my mother.” Mrs. Whitman helped her mother get up and got her into bed. She cleaned up the blood, for although Emma didn’t realize it at the time, her mother had had a miscarriage. “She was a wonderful woman, that Mrs. Whitman.”

Many Russian and German Jews spoke Yiddish at home in those days, and so did the Neibergs, which made the study of German easier for their children in later years, although the pronunciation was different. (Yiddish, a language derived from German, with an admixture of Hebrew and Slavic languages, was often spoken among the Jews of Eastern Europe. In America it had almost died out until recently, when the discovery of a treasure trove of old books and newspapers sparked a revival. The well-known writer Isaac Bashevis Singer wrote in Yiddish.) Emma said that at home Yiddish was spoken, but she learned English too, and of course when she went to school the classes were entirely in English.

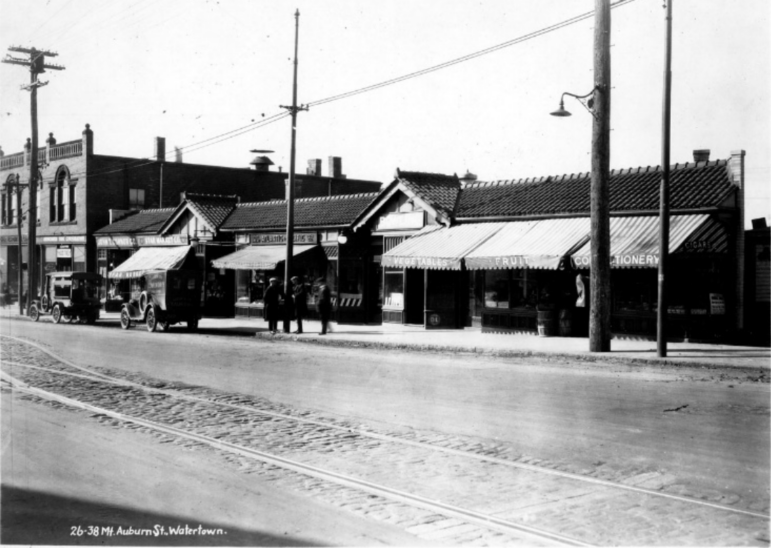

When she was in her senior year at the High School, Emma went across Mt. Auburn Street and asked Stephen Mugar, who had his grocery and butcher shop in the Star Market’s first location,

if he needed help with his accounts. Steve’s sister Helen, she says, was in her class in the High School. “Come to think of it, I believe Steve had an older sister; her name was, I think, Mary,” she muses. This began a business relationship that lasted ten years, from 1929 until Emma married in 1939. (It must be remembered that in those days and until as recently as fifty years ago, when a young woman married, it was customary for her to quit her job and become a homemaker, unless she worked in the family business to help her husband.)

Emma Neiberg was Steve Mugar’s first bookkeeper, and she worked in an office upstairs over the shop, keeping the market’s accounts in a big ledger. According to Emma, Steve Mugar liked to keep busy downstairs doing his meat-cutting, for he had taken over the business when his father died. His motto was “Take care of the customer, and the customer will take care of you,” and he became famous for emphasizing customer service. Steve, however, didn’t have the time or the inclination to keep accounts, so he would call up the stairs to Emma when he made a sale, or give her slips of paper on which he had noted a transaction. She said she used to work as much as fourteen hours a day when she worked as Steve Mugar’s first accountant at the Star Market.

One day Steve Mugar suggested to Emma that she ask one of her teachers if she’d like to bring a High School class to visit the Star Market, where Steve would show the class how meat-cutting was done. Emma’s home economics teacher was Marian Graves, who liked the suggestion, and so it was arranged that the class would come to the market from school at 1:30 in the afternoon on a school day. Emma’s teacher and her classmates enjoyed the visit to the Star Market, and Steve bought ice cream cones for all the children at Whitney’s candy store around the corner. In fact, things went so well, and Steve Mugar liked their teacher so well, that he invited her to go out with him. According to Emma, he took Miss Graves to dinner and to the Colonial Theatre to see a show, and eight months later they were married. “And so,” says Emma, “I was the one who actually introduced Steve Mugar to his future wife.”

Emma had her own romance when she met her future husband, Hyman Taylor, through her friend Bessie Shick. Bessie had a date with a young man. Her date had a car — unusual in those days – and suggested that he bring a friend, and that Bessie bring one, too, Bessie asked Emma if she’d like to make a fourth. To Emma the blind date sounded romantic, and so it turned out to be. “What did you do on this date?” I asked. “Oh,” said Emma, “We went to the movies in Harvard Square.”

Hymie, as the young man was called, had gone to Boston University and the Bentley School of Accounting, which was for many years on Newbury Street in Boston, and was now employed by his uncle in the retail leather business.

Emma and Hymie hit it off right away, but when Hymie told his mother, a widow who lived in Dorchester, that he’d fallen in love with a girl who lived in Watertown, she said, “All right, you can go ahead an marry that girl in Watertown if you like, but remember, I’m you mother and you have to take care of me.” So according to Emma, half of Hymie’s paycheck went to his mother every week until she died.

When I asked if Hymie’s mother had worked to rear her three children on her own after her husband died (when Hymie was only seven years old), she sniffed, “As far as I know, that woman never did a lick of work in her life, nor did her daughter, who lived with her, either.” Emma admits that she didn’t get on very well with her mother-in-law. When they married, she and Hymie rented an apartment in a house at the top of Palfrey Hill. Emma’s parents rented half of a two-family house at the bottom end of Palfrey Street, and Jacob, her father, operated a cleaning business on Spring Street nearby for many years. When the son of the woman who lived in the other apartment ran his bicycle pell-mell down the hill and into Spring Street, where he was killed by a passing car, the mother couldn’t face staying in the house, and so Emma and Hymie moved into the vacated apartment. “The traffic on Spring Street was terrible in those days,” said Emma. “But we liked living there, and we got along fine with my mother and father.”

How did Hymie get the name Taylor? I asked, for it didn’t seem to be the surname of a Russian Jew. Oh, said Emma, the family name was actually Liederman. When the family came to Ellis Island, like many immigrants speaking no English, one branch retained the name, while the other, when asked their occupation and replying that they were tailors, was given the name “Taylor.”

One of the Liedermans went to San Francisco, survived the earthquake of 1906 and became a Cantor, appropriately because the name actually means “singer” in German. Hymies’s uncle, for whom he worked, never resigned himself to Hymies’s father’s having changed his name from Liederman, according to Emma. But of course in those days it was quite common for immigrants to undergo name changes in order to sound more “American” (i.e. “Anglo”), either by their own

choice or by following an immigration officer’s suggestion.

Emma and Hymie had two children, Marilyn and Alan, who both went to college, Marilyn to Barnard, and Alan to Northeastern. Marilyn married Sheldon Binder, who is a surgeon, and they live in Belmont. Their daughter went to Connecticut College and then on to become a veterinarian, and their son to Clark University where he took a degree in meteorology. Emma’s daughter Marilyn comes to the Marshall Home to see her mother almost every day except Thursday, when shoe goes to do the grocery shopping, just as was her mother’s and grandmother’s custom in the old days in Watertown Square.

I remember a Neiberg family that lived on the corner of Marshall And Spring Strret in the sixties and early seventies. Mr Neiberg was a “junkman” and had a truck in the driveway. He and his wife used to let us kids play in the yard and in the truck. I remember there were piles of newspapers that we used to sit on. I think they had a dog, as well, possibly named Ziggy. Mrs Neiberg often gave us cookies which we would then eat in the back of the truck. I think their daughter lived downstairs for a brief time with her son, David, who would have been around 5 years old in 1969. I wonder now if the two families were related.

Fabulous article! Thank you so much for publishing this historic account.

Hi, Christine, And I remember in the late 1970s that the Taylors lived next door to Mr and Mrs Israel on Spring near the corner of Palfrey. I’ll have to go say hello to Mrs Taylor–her family and friends were all very sweet when I walked around the neighborhood with our two sons and dogs so many years ago. Front porches certainly contribute to making a neighborhood a wonderful place to meet and greet. Thanks Sigrid for the update to this little bit of Watertown history.