The following article is part of a series on local history provided by the Historical Society of Watertown. It was written by Sigrid Reddy Watson for a 1994 program at the library and printed in the June 1995 Historical Society newsletter, “The Town Crier”. Sigrid is a former Board member and former President of the Historical Society, as well at a former Director of the Watertown Free Public Library. For several years starting in 1997, she wrote a Watertown history column for the Watertown TAB/Press called “Echoes.”

On November 16, 1994 a joint meeting between the Friends of the Library and the Historical Society of Watertown was conducted in the Pratt room of the Free Public Library. The meeting was dedicated to the late Charles T. Burke, who had a significant impact on both of these organizations during his life. The program consisted of an illustrated lecture on the events that led to the establishment of the Free Public Library in Watertown and was given by Sigrid Reddy Watson.

We have included the text of Sigrid’s speech and some of the photographs, courtesy of the Free Public Library in Watertown, for the benefit of those who were not able to attend. For those who were, this printing will give you an opportunity to linger over the information that was presented to us.

In this talk I shall attempt to trace the evolution of the intellectual and social climate in Watertown, and in the nation, that led to the establishment of free public libraries in general and to the Watertown Public Library in particular. I plan to refer in this talk to examples of people and places relevant to these events, most of which took place during the 19th century.

Watertown, as we know, was the first inland settlement in Massachusetts. The settlers of the Massachusetts Bay Colony on the ship “Arbella” had arrived to found Salem, but it was not

long before a dissident element left to establish a community in Watertown, up the Charles River from Boston, which was established in the same year in what is now Dorchester. The years before the Revolution were spent dealing with the Indians, defining the Town’s boundaries, quarreling about the location of the Meeting House and establishing trade and commerce, for Watertown stood at the crossing place on the Charles River for the stagecoach route on the road west. Freight was unloaded here for transport overland. Mills, shops and taverns clustered below the falls. Trees felled upstream were floated downstream to Boston.

The Revolutionary War period saw the Provincial Congress assemble in the Fowle House. Paul Revere printed Provincial currency here. George Washington visited here on his way to take command of the troops in Cambridge, staying overnight at the Coolidge tavern. Trade and commerce continued their growth around the Grist Mill, which stood near the river crossing for three hundred years. In New England, after the Revolution, the First Parish represented the Established Congregational Church; the Town maintained the meeting house and the clock in the church tower.

Although the governing class was identified with the Congregational Church, many citizens were not active in church affairs, having come to the new world for other reasons than the search for religious freedom. Some, for example, were indentured servants working to earn their freedom from their masters; others were fortune hunters. Although the first religious “Great Awakening” had taken place in the Colonies beginning early in the 18th century, it was not until early in the 19th century, with independence from British rule, that there occurred a new religious revival, a declaration of independence from conformity. Throughout the country, people had arrived with different religious convictions. The release from pressure to conform, together with the disestablishment of the Congregational Church and the withdrawal of support from the local government (in Watertown in 1837) led to greater desire for religious freedom in New England. The Baptists and other Protestant denominations felt that they should not have to pay the Church tax, and went on to build their own churches in Watertown.

The influence of Transcendentalism in the new Unitarian movement divided the Congregational Church and led to the orthodox Congregationalists, who still believed in the Trinity, leaving the First Parish to found the Phillips Church. Transcendentalism, reflected in the writings of Ralph Waldo Emerson, was important in generating a movement for the abolition of slavery throughout the North. It affirmed a belief in the divinity of human nature and appeared as intense individualism in some, and in others a passionate sympathy for the poor and oppressed. Convers Francis, the minister of Watertown’s Unitarian Church, was outspoken against slavery. Here also, Theodore Parker started a school. He was ordained in 1841 and became a famous abolitionist orator. While opposition to slavery was not by any means universal in the North, among the intellectual leaders in the Boston area it became a major cause.

Lydia Maria Francis Child, the sister of Convers Francis, lived with him and his wife In the house on Riverside Street, established a school, wrote polemics denouncing slavery and edited the “National Anti-Slavery Standard” for William Lloyd Garrison, publisher of the “Liberator.” Henry Ward Beecher, the brother of Harriet Beecher Stowe, author of “Uncle Tom’s Cabin.” preached at the Phillips Church. During the 1840’s 150,000 people joined anti-slavery societies. James Russell Lowell, a Harvard professor and poet, who married Maria White of Watertown, was active in the movement. Senator Charles Sumner, whose statue by Anne Whitney stands in Harvard Square, spoke so offensively in the Senate Chamber against slavery in 1856 and so insulted his colleagues from the South that he was severely beaten on the Senate floor by Senator Preston Brooks of South Carolina. In 1857, the Dred Scott case further polarized opinion between the South and the North, demolishing the agreement embodied in the Missouri Compromise. Dred Scott, a slave, and his wife had been taken into free territory by their master and petitioned for their freedom in the court at St. Louis. After decisions and appeals, the case reached the Supreme Court, where Chief Justice Taney handed down the decision denying the petition, asserting among other things that negroes had no right to freedom under the Constitution. One of the dissenters to this decision was Benjamin Robbins Curtis, who, with his brother, had been brought up by his widowed mother in Watertown, had gone to Harvard and later had been appointed to the Supreme Court by President Fillmore. He was so outraged by what he considered a bad decision that he resigned from the Court and resumed private practice, later defending President Andrew Johnson in his impeachment hearing.

The movement for the abolition of slavery was supported not only by great writers and preachers like Emerson, Parker, Lowell and Sumner but also by such women as Harriet Beecher Stowe, Lydia Maria Child and Lucy Stone Blackwell. Lucy Stone was descended from Gregory Stone, who with his brother, Simon, had settled in Watertown in 1635. She was a champion of women’s rights as well as those of slaves, and converted Susan B. Anthony to the cause in 1850 at the first National Women’s Rights convention in Worcester. Lucy married Henry Blackwell, an abolitionist and brother of Elizabeth Blackwell, an early woman physician. Lucy became a Unitarian, and for many years edited the “Woman’s Journal.”

In addition to supporting abolition, women’s suffrage and the temperance movement, Watertown women were active in the literary life of Massachusetts. James Russell Lowell married Maria White, whom he had met through his classmate, William White. Maria Lowell had a cousin, Levi Thaxter, whose home stood on Main Street. His wife, Celia, wrote poetry reflecting her love of nature, and in 1851 “The Atlantic Monthly” published one of her poems, which had been sent in without her knowledge by Maria’s husband James. Celia’s birthplace on the Isle of Shoals eventually became a Unitarian conference center.

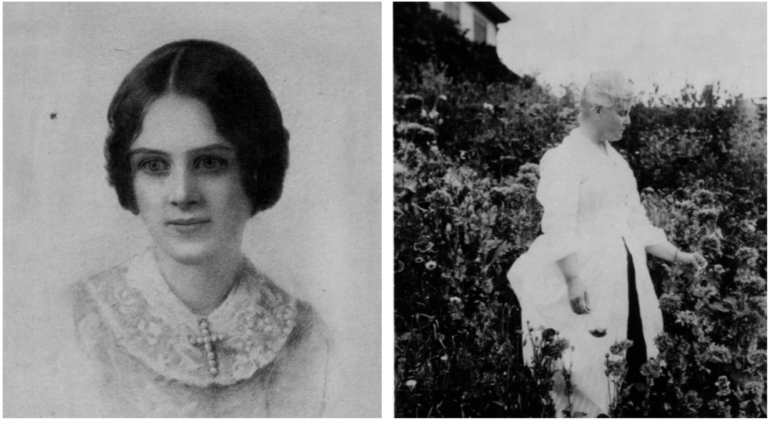

The cultural life of Watertown was enriched by other women artists, among them Ellen Robbins, another cousin of the Thaxters and Curtises. She showed her love of nature by doing watercolor paintings of flowers, several of which are in the library and the Historical Society. She also painted a charming picture of Celia Thaxter in her island garden. Although education for women in the mid-19th century differed from men’s and few attended college (Lucy Stone, who graduated from Oberlin, was an exception), schools for the education of females were founded by Lydia Maria Child and others, and we must not forget that Henry Fowle Durant and his wife, Pauline, founded Wellesley College. With the focus on intellectual, political and cultural activities, Watertown produced other women artists who attained international renown. Anne Whitney, a cousin of Lucy Stone’s, developed her considerable talent for sculpture by studying in New York and Philadelphia and spending four years in Rome. In the library, she is represented by a bust of Keats and the plaster figure of Charles Sumner. You may have heard the story that in the anonymous contest she entered for the commission for the statue of Sumner, her work was rejected when the judges discovered that the sculptor was a woman. She was ultimately vindicated, however, when a group of her admirers commissioned the sculpture which now stands in the center of Harvard Square.

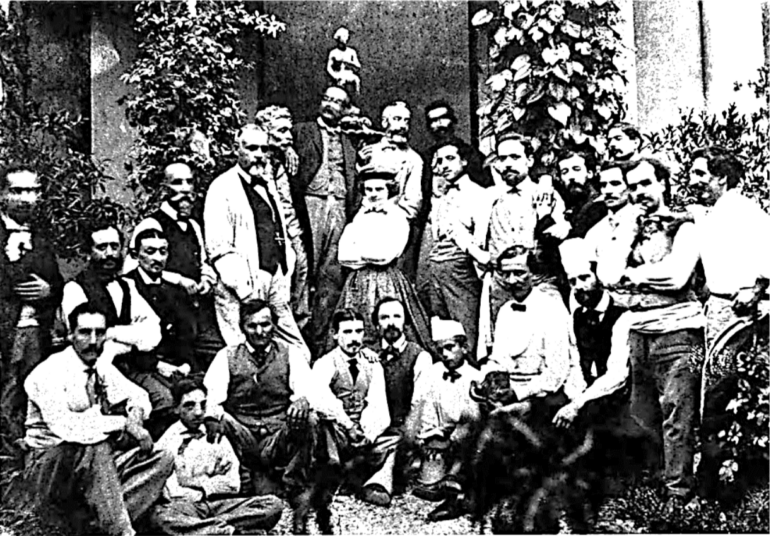

Harriet Hosmer, a classmate of Ellen Robbins at the Bird Singing School, needs no introduction here after the complete and interesting talk Father Curran gave last year about her life and work. Born in Watertown, she was internationally celebrated, made friends in her studio in Rome and on the Continent, and, like Anne Whitney, had to contend with the still prevailing notion that women’s work was not to be taken seriously. Harriet began her studies in Rome in 1852 and lived into the twentieth century. In her old age she returned to Watertown where she died in 1908. The library is fortunate to own more examples of her works than are contained in any other place.

The mid-nineteenth century was a period of industrial growth and development which not only changed the face of America but permitted the establishment of some of the great fortunes which made culture and leisure possible. The railroads to the West were laid and although local routing through Watertown by the Boston and Albany was opposed locally, there were spurs laid to the East Watertown district, and also a line of the Fitchburg railroad. In the period preceding the Civil War, the Whitneys established a paper mill. The Hollingsworth and Whitney Company and the Bemis Mills, which had woven cotton cloth since before the Revolution, turned to weaving woolen textiles and became the Aetna Mills. (The museum at the old Aetna Mill Building on Pleasant Street is well worth a visit.) Alvin Adams founded the Adams Express Company, which prospered during the Civil War. Adams later bought the magnificent old Davenport mansion, called “Fountain Hill”, on School Street. Lewando’s Cleaning Service bought out a dyehouse that had been on Pleasant Street during the Civil War and employed many Watertown people. In addition to the textile business, shirts were manufactured in Watertown.

Miles Pratt built a foundry in 1855 next to the old grist mill, where he manufactured stoves. The Walker and Pratt foundry was later moved to Dexter Avenue, close to the railroad tracks, where the company manufactured furnaces and, later, the famous Crawford Range. Banks were founded to furnish capital for the development of businesses. One of the first was the Watertown Savings Bank, founded in 1870 by Charles Barry, who had married Abby Bemis, and Joshua Coolidge. Nathaniel Whitney was the third founder. Deposits totalled $924 on opening day.

Governor Gore had built his summer home in what was then Watertown, and Harrison Gray Otis “The Oakley,” later to become The Oakley Country Club. The country flavor of the town, with its market gardens and eighteenth-century houses, was gradually obliterated by the effects of the Industrial Revolution.

The mid-century climate of prosperity fostered not only the arts but education. The concept of the perfectibility of man engendered a strong movement toward education for everyone, an idea that came out of the visits that persons like Horace Mann had made to Europe. Samuel Gridley Howe became the first director of the Perkins School for the Blind in Boston in 1830. Although Theodore Parker and the Unitarians preached for prison reform and the rights of factory workers, many Congregationalists, Baptists, Presbyterians and Methodists believed the Unitarians were close to atheism, while they enjoyed the support of the nativist evangelical wing of the Protestants. From this yeasty mixture came the impulse toward compulsory elementary and secondary education. Colleges had originally been established, as we know, for the education of the ministry, but this higher education was only for the elite and moneyed class. Horace Mann became the new Commissioner of Education in Massachusetts in 1837. In Massachusetts, as in most Northern states, primary education was free and soon compulsory, although at first this was resisted, as church attendance had been, being viewed as infringing on the rights of parents to the use of their children’s time and energy. In Watertown, the Town Hall was built in 1846, and the town established a high school in 1853. There were three school districts, containing the Coolidge School in East Watertown, the Howard Street School in the West End and the Brick School in the center of Town, later superseded by the Francis School.

The desire of citizens to support education and to make books available to all was a New England tradition. In 1799 a subscription library was established in the Bird Tavern, and was open for two hours each month, with a collection of 235 books. Benjamin and George Curtis’s mother kept a circulating collection in her shop from 1818 to 1825. In 1851 the Commonwealth passed legislation permitting cities and towns to appropriate money from taxes to support public libraries. Boston founded its library in 1852.

In addition to religious ferment, the movement toward liberating slaves and women, and the growing strength of labor, there ultimately developed societies and organizations of like-minded people who built clubhouses where they could gather for social purposes. In Watertown, there were Masons, Elks, Oddfellows, and, not to be outdone, Catholics organized The Sons of Italy, the Knights of Columbus and the Hibernians.

In 1859, the pending execution of John Brown, deemed a traitor because of his abortive raid on the arsenal at Harper’s Ferry, precipitated a call to a meeting on November 30 at which protests could be registered and discussion of “material aid” to his family could be conducted. Many prominent citizens signed the call to this meeting.

The Watertown Arsenal played a important role in the Civil War. Established in 1816, after the War of 1812, the Arsenal had a machine shop and forge where guns, ammunition and cannons were manufactured. Nearby foundries, such as Walker and Pratt, were also contracted to produce iron castings. The Arsenal produced the famous Rodman Gun, named for Thomas J. Rodman, who then was Commanding Officer at The Arsenal. Many Watertown men served with distinction in the Union Army, although it must be said that as enthusiasm for the bloody war abated, many a reluctant soldier took advantage of the opportunity to pay for a substitute. When the war was over, Watertown citizens turned their attention to the establishment of a public library. Joseph Bird, son of Jonathan Bird of the Bird Tavern, had obtained in 1866 subscriptions for a library in the high school, and it was enjoyed by the community, then numbering about four thousand. So in 1867, the School Committee appointed Dr. Alfred Hosmer, Harriet’s cousin, the Reverend John Weiss, minister of the Unitarian Church, and Joseph Crafts, a prominent citizen, to investigate the feasibility of obtaining better space. Soon the Town Meeting appointed a Board of Trustees, and appropriated $1000 for their use in setting up a library, which was eventually placed in the old Town Hall in the rooms vacated by the storekeeper Joel Barnard. $6000, a generous amount, was allocated for the purchase of books. The first annual budget totaled $1,399.59, of which $500 was the salary of the librarian. The first librarian to be selected was Solon Whitney, and since he was also principal of the high school, we can assume it was not a full-time job. You may see his portrait in the Hunnewell Room, as well as those of Charles Barry, Joshua Coolidge (two of the founders of the Watertown Savings Bank) and John Weiss, the minister of the Unitarian Church, early trustees.

The library opened in the Town Hall on March 31, 1869.

During the early years, the Library’s book collection was the subject of controversy. After the establishment of public schools, and the controversies surrounding the issues of the mid-century period, library collections emphasized education and uplift, focusing a good deal on biographies of famous men for inspiration. The Trustees’ duty was “to inspire and educate” and, one trustee, Mr. C.F. Fitz, was so fractious in his opposition to the library’s purchase of fiction that on March 3, 1882, the Trustees barred him from attending meetings. Solon Whitney, however, seems to have been appreciative of the popularity of fiction, as it constituted 65% of the circulating collection in 1883.

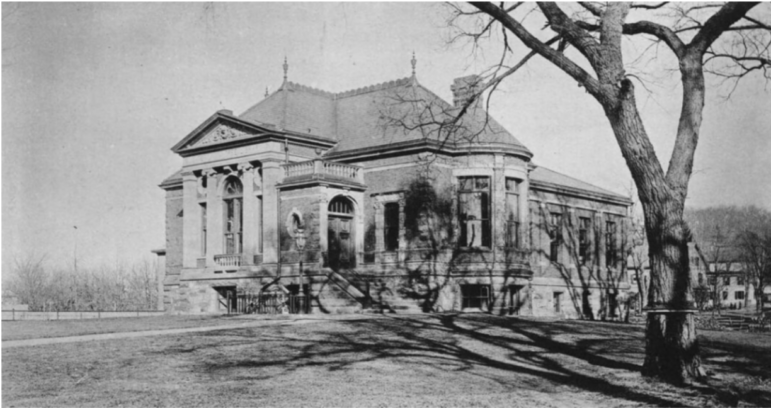

By 1881, the need for a library building was apparent. Hollis Hunnewell of Wellesley offered $10,000 toward the new building, which was designed by Shaw and Hunnewell. It cost $27,000 and opened February 1883. In 1888 Charles Pratt gave $5000 in memory of his father, Asa Pratt, a local cabinetmaker. Charles Pratt had made a fortune manufacturing paint and eventually became a partner of John D. Rockefeller in the oil business. The income from Pratt’s gift was to be used for periodical subscriptions, for he believed that working men should be allowed to come into the library to read newspapers, in their shirtsleeves if they wished. In 1899, Hunnewell gave the new library an addition containing the Hunnewell Room, and underneath it, the Pratt Room.

In 1888 a group of interested citizens organized the Historical Society. This was a period in which, with the interest in science, history and genealogy, many towns in New England saw the founding of societies of natural history, public libraries (which often served as museums as well), and historical societies. Eventually the Historical Society found a home in the Edmund Fowle House, and recently succeeded in having it listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Much more could be said about the Library and the Town after the end of the 19th century, but perhaps that could be deferred to another occasion. Mr. Whitney served the Library for 49 years, until 1917, and was succeeded by Lydia Masters, who had worked as his assistant in the Library since 1898, and who was Librarian until 1946. Appropriately, Miss Masters was descended from the Bird family.

The town grew and changed. Main Street no longer had the old Town Hall, which was replaced by a beautiful new WPA building. The Barnard Block was demolished. In 1935 Watertown Square’s Delta had become a traffic circle.

Through the period before and after World War I, Watertown prospered, becoming an industrialized working-class town. Many immigrants from Canada, Italy, Ireland, Armenia and Greece came to live in Watertown and work in its factories. Lewando’s Cleaning & Dyeing Company flourished on the Charles River. The Hood Rubber Company and the stockyards employed hundreds in East Watertown. Local businessmen organized the Chamber of Commerce in 1927. Watertown had become a street-car suburb.

During the Depression, library readership increased. The North Branch was established in 1927 in the old Lowell School, a newly remodeled building opened in 1941. In 1930 the West Branch opened in the Browne School. In the East End, the storefront library was replaced by a new building during the administration of Catherine Xerxa, and the Friends of the Library was organized. The High School building became the Phillips School. G.Fred Robinson, active in town affairs for 65 years and an active member of the Historical Society, published “Great Little Watertown”* and, the Historical Society, one of the earliest, met in the Concord house of Helen Robinson Wright. Finally in 1980 the library, with the help of the Barry Wright Company and a town appropriation, published Maud Hodges’ history of Watertown, “Crossroads on the Charles.”

Charles Burke, a trustee for nearly 50 years, read the manuscript for accuracy and make a number of useful suggestions. And to quote from Mr. Burke, whom we honor this evening, “The Watertown Library, in history of more than a hundred years, has had only six librarians, and, I have known them all!”

The picture of the First Library was the one of my youth. Now I lived in Watertown 1948-1962. There was during this time no new addition. The Children’s library was in the basement. Many a Saturday was spent their while my Mom would be upstairs in the Adult section. I always loved the smell of the library. comforting and old from the smell of books and polish. I could have lived there if they never closed or locked the doors.

The title of this essay led me to believe it would devote more than two paragraphs to Watertown’s 20th century history, a period that saw the town’s most dramatic growth. The ethnic groups cited in one sentence, and only one sentence, played a large part in that growth. How curious, then, that virtually the entirety of the article is devoted to the 19th century and the contributions of white, Anglo-Saxon Protestants. Such historical particularism does a grave disservice to your readers.