The following story is part of a series on local history provided by the Historical Society of Watertown. It was written by Historical Society board member Mary Spiers who served as the Recording and Corresponding Secretary, and retired from the board last month but is still a volunteer. She wrote this article for our April 2014 newsletter, “The Town Crier”.)

I have to credit the blizzard of February, 2013 for the inspiration to pick up a copy of Snow-Bound by John Greenleaf Whittier and thereby find this nugget of historical gold on Mercy Otis Warren. I also utilized the library at the Massachusetts Historical Society to research Mercy’s poems.

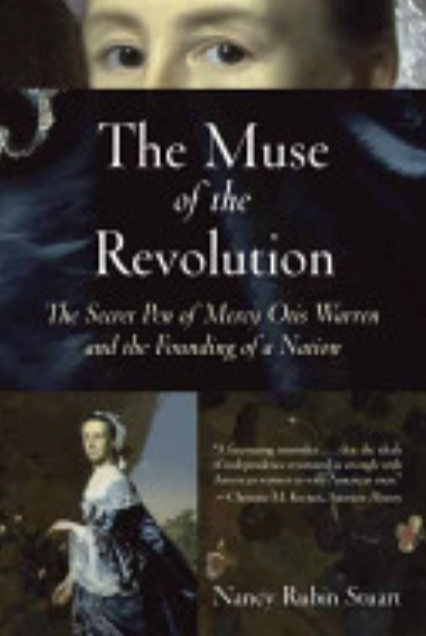

Mercy Otis Warren born in 1728, who we think of today as “the Conscience of the American Revolution” and a “Founding Mother,” is the graceful lady in the blue dress in the John Singleton Copley iconic portrait of her that hangs in the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. A copy hangs on the walls of the Edmund Fowle House, now home to the Historical Society of Watertown. This house was in 1775 a scene of much bustling activity as the seat of the provincial government during the outset of the War for Independence.

Following the death of Dr. Joseph Warren at the Battle of Bunker Hill in June, 1775, the title of President of the Massachusetts Provincial Congress was succeeded to by attorney James Warren whose Executive Council met at the Fowle House. The Legislative Body met in the near-by meeting house on the edge of the Common Street Cemetery. James Warren lived at the Fowle House as time would allow, that is, when he wasn’t traveling about as Paymaster General for General Washington’s Continental Army or on an assignment for the Sons of Liberty and other duties associated with the war effort.

His actual farmstead was in Plymouth, set on land familiar to his Mayflower ancestors and now overseen by his wife and mother of his five sons, Mercy Otis Warren. She would visit James in Watertown when she could. She like her husband had been raised on Cape Cod with her father circuit judge and wealthy merchant in West Barnstable. They lived in a mansion surrounded by acres of land with a foreman to manage an assemblage of farm laborers including indentured servants, American Indians and at least one African slave. Mercy was one of thirteen children, only seven of whom survived to maturity. Her mother was Mary Allyne Otis, a great granddaughter of Mayflower passenger Edward Dotey. With the loss of six infant siblings, Mercy found herself as first daughter, a key player in running the household.

During her lifetime, Mercy Otis Warren wrote and published many poems anonymously and in 1790 wrote a volume of poems and plays entitled Poems, Dramatic and Miscellaneous. In 1805 at the age of 77, she published her magnum opus, her three-volume, The History of the Rise, Progress and Termination of the American Revolution — the first history of this event written by a woman.

One of Mercy Otis Warren’s verses found its way into the work of Quaker abolitionist and poet, John Greenleaf Whittier when he composed his memorable and much-loved poem Snowbound: A Winter Idyl. She died in 1814 when the yet-to-be Fireside Poet was only 7 years of age. Yet there was a common belief held by both and spanning time and place: a respect for the dignity of man and a love of freedom for all. When Whittier’s poem was published by Ticknor and Fields in 1866, our country was in great need of tender mercies. The poet writes: “We sped the time with stories old, Wrought puzzles out, and riddles told, Or stammered from our school book lore ‘The Chief of Gambia’s golden shore.’” How often since, when all the land Was clay in Slavery’s shaping hand, As if a trumpet stirred, I’ve heard Dame Mercy Warren’s rousing word:

“Does not the voice of reason cry,

Claim the first right which Nature gave,

From the red scourge of bondage fly,

Nor deign to live a burdened slave.”

In the same way, her brother, the patriot James Otis, espoused a soul-stirring plea in his “The Rights of the British Colonies Asserted and Proved” in 1764: “… slavery is so ill and miserable an estate of man, and so directly opposite to the generous temper and courage of our nation, that ‘tis hard to be conceived that an Englishman, much less a gentleman, should plead for it.”

Perhaps it was the old rural New England custom of gathering together the field hands at the main meal in either the kitchen or the dining room that brought young Mercy into acquaintance with the less fortunate in her farm household. She came to know and appreciate early on what working together for the common good meant and she never forgot. Whittier, in turn, honored her yearning for the slave to breathe free. We in the present can see her better now thanks to Whittier, as more than just a brilliant thinker, but as a woman of history, clearly ahead of her time.

In 2008, award-winning author Nancy Rubin Stuart wrote a book drawn from the correspondence of Mercy Otis Warren, much of it published for the first time. The Muse of the Revolution: The Secret Pen of Mercy Otis Warren and the Founding of a Nation is available for purchase in stores for $28.95 and at the Edmund Fowle House for $15.00. To purchase a copy please contact Joyce at joycekel@aol.com.