By Bill McEvoy

In honor of Memorial Day, local historian Bill McEvoy has compiled histories of some of the Civil War clergy who are buried at Mount Auburn Cemetery. This is part one of 15.

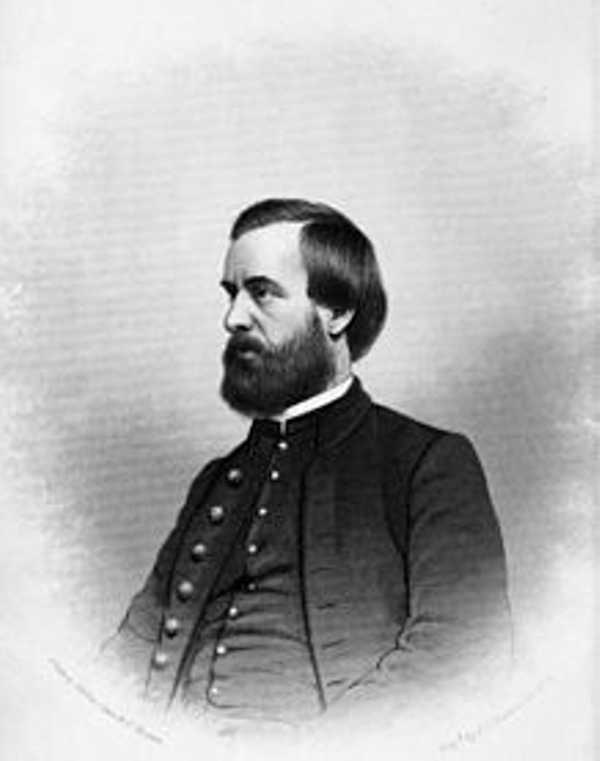

Reverend Arthur Buckminster Fuller was born August 10th, 1822, at Cambridge, Massachusetts. He died on December 11th, 1862, at Fredericksburg, Virginia of multiple gunshot wounds, inflicted by Confederate Sharpshooters.

He was raised in Cambridge and Groton. He prepared for college under the direction of his sister Margaret Fuller Ossoli, a teacher of extraordinary gifts and influence, then at Sarah Bradford Ripley’s school at Concord. Mrs. Ripley also taught Ralph Waldo Emerson.

Reverend Fuller entered Harvard in 1839 and graduated in 1843. During his college years, he taught at a district school in Westford and Duxbury.

Upon graduating he started for the West and invested what remained of his inheritance purchasing a school in Belvidere, Illinois

Early in this experience he took to preaching, and became a lay missionary, preaching and lecturing throughout a wide extent of territory, often in cooperation with his friend and neighbor, Augustus H. Conant.

In 1845, he closed the school, due to illness. He returned home and entered the Harvard Divinity School, where he graduated in 1847.

After graduating he preached for a few months at Unitarian Church in West Newton, Massachusetts.

The next year he was ordained a Unitarian minister and became the Pastor of the Unitarian Society in Manchester, New Hampshire. In September 1852, he was called to by the New North Church in Boston to become their Pastor. He indicated that he was content to remain in Manchester Society.

Later he was called again, in early, 1853, and on, June 1, 1853, he was installed as the Pastor of the New North Church in Boston.

In 1856, he edited the writings of his sister Margaret, At Home and Abroad, or, Things and Thoughts in America and Europe

He remarked, “if I only live to send forth Margaret’s words from the press, as they should appear, I shall not have lived wholly in vain.”

Again, failing health, and the fact that the Protestant population was rapidly leaving the North End, caused Reverend Fuller to resign his Pastorate, and close his labors there on July 31, 1859.

He then served at the Unitarian Church in Watertown, Massachusetts.

He took an active part in educational, temperance, and anti-slavery work, and was twice chaplain of the Massachusetts legislature.

When the Civil War began, Reverend Fuller resigned his pastorate in Watertown to enlist.

On August 1st, 1861, he received a commission as Chaplain in the 16th regiment of Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry and immediately went to the front.

After doing good service as a minister of religion and a friend to the living and dying, both in hospitals and on the field of battle, he volunteered as a soldier.

Knowing the danger ahead, he said: “I am willing to peril life for the welfare of our brave soldiery and in our country’s great cause. If God requires that sacrifice of me, it shall be offered on the altar of freedom, and in the defense of all that is good in American institutions.”

At first, the regiment saw little action. Reverend Fuller busied himself assisting in the post-hospital, holding church services, and teaching reading and other lessons to foreign-born soldiers and escaped slaves.

He loved his fellow soldiers and they admired him in return. His services drew congregants of every faith, including Roman Catholics. They were so lively and well-attended that chaplains of other denominations, when going on leave, frequently asked him to substitute for them.

In March 1862, from a vantage overlooking Norfolk Bay, Reverend Fuller witnessed the battle between the Confederate ironclad, the Merrimack, and the much smaller Union ironclad, the Monitor.

He wrote one of the most accurate, useful, and comprehensive eyewitness accounts. After fighting to a standoff, the Merrimack retired from the scene of battle, and Fuller rejoiced. “David had conquered Goliath with his smooth stones, or wrought-iron balls, from his little sling, or shot tower.”

When they were finally called to arms for the Peninsular Campaign, at Eastern Virginia, in June 1862, the chaplain was pleased. “I know no holier place, none more solemn, more awful, more glorious than this battlefield shall be.”

For many days the Sixteenth Massachusetts was engaged in combat, their “baptism in blood,” as Fuller referred to it. Unlike some other volunteer chaplains, he went onto the battlefield with the men, shouting encouragement, leading prayers, and tending the wounded.

When his battered regiment was withdrawn from the battlefield, he was so weak and ill that he was forced to return to Massachusetts.

Throughout the summer his family feared for his life. Nevertheless, in October, in somewhat improved health, he set off to rejoin his regiment. He was warmly greeted by the combat-hardened men. He reported, “My own family could not be more cordial and more affectionate,”

As the regiment moved toward Fredericksburg, Reverend Fuller, under orders from the surgeon, remained behind. While recovering he ministered to the wounded in nearby hospitals.

To his great disappointment, however, doctors soon declared him unfit for duty. “You can hardly realize the pain I felt when I found I could not share the field campaign without throwing away health and life,” he had written to his wife. He was consoled by the promise that an opening would be sought for him as Chaplain of an Army hospital.

On Sunday, December 7, the regiment came together at the close of the dress parade to hear Chaplain Fuller’s farewell address. Two days later Fuller wrote his wife that he was coming home, with no misgivings. “If any regret were mine, it would be that I am not able to remain with my regiment longer; but this is, doubtless, in God’s providence.” On December 10, Fuller was honorably discharged as having a disability.

The following morning Reverend Fuller lingered with his regiment, which was preparing to assault the city of Fredericksburg. Army engineers constructing pontoon bridges to cross the Rappahannock River they came under heavy fire from Confederate sharpshooters. A call went out for volunteers to change tactics by manning rowboats for an assault on the enemy.

Reverend Fuller did not hesitate. Although no longer officially part of the Army, the frail, forty-one-year-old civilian climbed aboard a boat for the hazardous crossing of the river.

Reaching the shore, he found himself with the Nineteenth Massachusetts Regiment, which was preparing to advance on the city. Chaplain Fuller stepped forward, notwithstanding the fact that he had been discharged from all obligation to serve, so that, if captured, he could not expect to be exchanged, and, if killed, his widow could not expect a pension.

Nevertheless, he volunteered and crossed the river as a private, musket in hand. He wore the uniform of a staff officer, which made him a special mark for the sharpshooters.

Captain Moncena Dunn of the Nineteenth later, wrote to Reverend Fuller’s brother and reported what happened to Fuller that day.

“I first saw him for the first time in the streets of Fredericksburg,” at about 3:30 PM where I was in command of 25 men deployed to the skirmishes. We came over in the boats and were in the advance of the others who had crossed. Pursuant to orders we marched up the street leading from the river, till we came to Third Street, traversing it parallel with the river on the street called Carolina Street.

We had been there but a few minutes when Chaplain fuller accosted me with the usual military salute. He had a musket in his hand and said Captain, I must do something for my country what shall I do?

I replied that there had never been a better time than the present, and he could take the place on my left.

I thought he could render valuable aid because he was perfectly cool and collected. Had he appeared at all excited I should have rejected the services. For coolness is of the first importance in skirmishes, and one excited man can have an unfavorable influence on the. I have seldomly seen a person on the field so calm and mild in his demeanor evidently not acting from impulse or martial rage.

His position was directly in front of a grocery store. He fell in 5 minutes after he took it, having been fired once or twice. He was killed instantly and did not move after he fell. I saw the flash of a rifle which did the deed.“

They were forced to withdraw after being unsuccessful in retrieving the bodies.

In addition to Chaplin Fuller’s to aid at a critical juncture in the affairs of his country, by the influence of his example and personal assistance, he may have been willing also to show that he had not resigned in the face of the enemy from any desire to shrink from danger.

Later there was speculation as to why Fuller would risk his life to accompany the Nineteenth Massachusetts, which was not his regiment, into battle. The Nineteenth Massachusetts’ own chaplain had long since fled. He firmly believed that men deserved a chaplain by their side during a fight. He was a Unitarian who believed that salvation required faith and works, and he had many friends in the Nineteenth. It was his Christian duty to go with them.

As a postscript, Mrs. Fuller received a widow’s pension by an act of Congress.

Find the gravesites of the Civil War Clergy by entering their name here: https://www.remembermyjourney.com/Search/Cemetery/325/Map Bill McEvoy can be reached at billmcev@aol.com