By Bill McEvoy

In honor of Memorial Day, local historian Bill McEvoy has compiled histories of some of the Civil War clergy who are buried at Mount Auburn Cemetery. This is part two of 15.

I am grateful to Reverend Daphne Noyes, retired Deacon of Boston’s Church of the Advent for her assistance in adding an additional background to Sister Tyler’s life.

The biography of William Rollinson Whittingham, Bishop of Maryland set apart, Adeline Tyler, as the first Deaconess in the Episcopal Church.

Per Deacon Noyes, most sources agree that these women were not ordained (laying on of hands, invocation of the Trinity) but were “set apart” — living under a rule, often but not always in community, under the direction of a Bishop. In Adeline’s case, that was Bishop Whittingham.

I also drew heavily from the: Project Gutenberg’s 2007 eBook release of 1867, text, Woman’s Work in the Civil War, by Linus Pierpont Brockett and Mary C. Vaughan

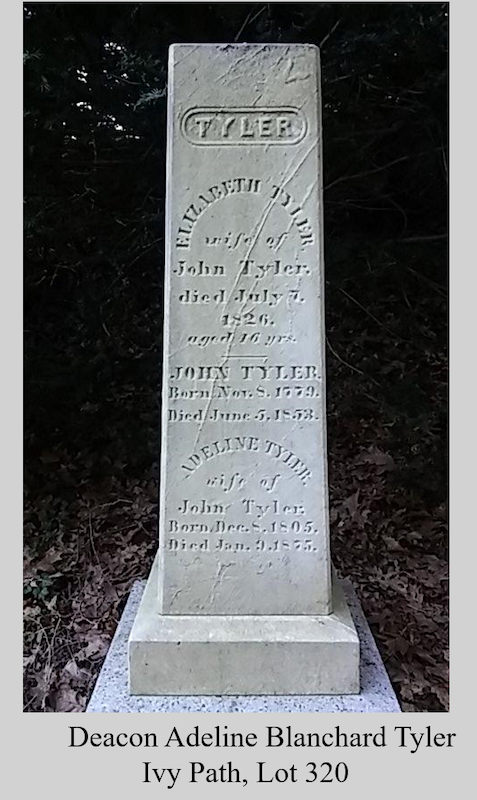

Adaline Blanchard Tyler was born on December 8, 1805, in Billerica, Massachusetts. On December 13, 1827, she married a widower, John Tyler, in Boston. She died January 9, 1875, at Needham, Massachusetts, from cancer.

As a resident of Boston her social position, piety, and benevolence were widely known. She was a devout member of the Protestant Episcopal Church, greatly trusted and respected by both clergy and laity.

In 1856, she went to Baltimore to assist Bishop Whittingham in establishing a school for the Protestant Sisterhood, also known as the Order of Deaconesses. It was to be like those already existing in Germany and England.

Mrs. Tyler, then a widow, was to assume the superintendence of that order. They were a band of noble and devout women turning resolutely from the world’s allurements and pleasures. They desired to devote their lives and talents to works of charity and mercy.

The order was to care for the sick, relieve all want and suffering, as well as providing spiritual comfort.

In addition to her general superintendence of the order, Mrs. Tyler had a variety of pious and benevolent duties. That included visiting the sick, and comforting the afflicted and prisoners. One day a week she visited the Baltimore jail. It was crowded, an abode of great crimes and suffering.

Mrs. Tyler became known as Sister Tyler and spent five years in Baltimore. Then the War began. Union troops were sent to Washington. One of the earliest was the Sixth Regiment Massachusetts Volunteers, the Lowell City Guards.

On the 19th of April 1861, as the regiment was hurrying to the defense of Washington, it was assailed by a fierce and angry mob in the streets of Baltimore. Several of its men were murdered, including 17-year-old Private Luther Ladd, who was proclaimed the first casualty of the Civil War

The news of the [243] riot reached Sister Tyler and she responded to the need.

There, she saw wounded men being conveyed to their homes, or to places where they might be cared for. The Police took many to one of the Station Houses. The Police told Sister Tyler the injured were to be cared for.

Sister Tyler was roused as this situation truly required works of “charity and mercy,” She saw this as her duty, in pursuance of the objects to which she had devoted her life. She needed to ensure the necessary care of these wounded and suffering men who had fallen into the hands of those so deleterious to them.

That afternoon. Sister Tyler went to the Police Station and knocked at the door but was denied entrance.

She was told that the worst cases had been sent to the Infirmary, while those who were in the upper room of the Station House had been properly cared for and were in bed for the night. She again asked to see them, adding that the care of the suffering was her life’s work and that she needed to assure herself that they needed nothing.

Told in a firmer tone, she was again denied. Her response was that she was a Massachusetts woman, seeking to do good to the citizens of her own state. If not allowed to do so, she would immediately send a telegram to Governor Andrew, informing him that her request was denied.”

With that, the doors were opened, and she has escorted to the upper room where the fallen patriots lay. Two were already dead and another. Several others were a bed, the rest lay in their misery upon stretchers.

All had been drugged and were either partially or entirely insensible to their miseries. It was about ten hours since they were wounded but no positive attention had been paid to them. The exception was having large pieces of cotton cloth trusted in their wounds. That was a feeble attempt to stem their bleeding. Their clothes had not been removed.

One of them (Coburn) had been shot in the hip, and another (Sergeant Ames) was wounded in the back of the neck, just at the base of the brain. He was apparently hit by a heavy glass bottle, as pieces of the glass yet remained in the wound. He lay in bed, still in his soldier’s overcoat, the rough collar of which irritated the ghastly wound. Those two were the most dangerously hurt.

With some difficulty, she was allowed to take those men, to her house, the Deaconesses’ Home. A surgeon was called, and their wounds were dressed. She extended to them the care and kindness of a mother until they were so nearly well as to be able to proceed to their own homes.

During this time, she refused protection from the police and declared that she felt no fear for her own safety as it was in the line of duties to which her life was pledged.

That was not the last sought of work by Sister Tyler. Other wounded men were received and cared for by her. One was a German, member of a Pennsylvania Regiment, (who was accidentally shot by one of his own comrades) whom she nursed to health in her own house.

On behalf of the Massachusetts men, she received personal acknowledgments sent from the Massachusetts Governor, President of the Senate, and Speaker of the House of Representatives. Later, resolutions of thanks were passed by the Legislature, that beautifully engrossed upon parchment, and sealed with the seal of the Commonwealth.

Sister Tyler had the full approval of her Bishop, as well as of her own conscience, as soon Bishop Whittingham appointed her Superintendent of the Camden Street Hospital, in the city of Baltimore.

Her experience in the management of her large religious institution made her familiar with many forms of suffering. Her natural tact, genius, and high character eminently fitted her for this position.

Sister Tyler fulfilled her duties admirably. She also came in contact with the members of some of the volunteer associations of ladies who, in their commendable anxiety to minister to the suffering soldiers, occasionally allowed their zeal to get the better of their discretion.

She did not live at the Hospital but spent the greater part of her time there during the year of her management. The charge she turned over to Miss Williams, of Boston, whom she had herself brought when she went north to visit her friends.

After a brief stay in New York City, she was asked by the Surgeon-General to take charge of a large hospital in Chester, Pennsylvania. It was just established and greatly needed the ministering aid of women.

She accepted the appointment and proceeded to Boston selected from among her friends, and those who had previously offered their services, a corps of excellent nurses, who accompanied her to Chester.

At that hospital, there were often from five hundred to one thousand sick and wounded men. Sister Tyler was supplied enough of ample stores of comforts which, by the kindness of her friends in the east, were continually arriving. There was never a time when she was not amply supplied with items, and money, for the use of her patients.

She remained at Chester a year and was then transferred to Annapolis, where she was placed in charge of the Naval School Hospital, remaining there until the latter part of May 1864.

During her stay, her staff attended the poor wrecks of humanity from the prison pens of Andersonville and Belle Isle. Her patients were an assemblage of misery and dreadful suffering.

It was a “work of charity and mercy,” never been presented by this devoted woman; such, indeed, as the world had never seen.

Filth, disease, and starvation had done their work upon them. Emaciated, till only the parchment-like skin covered the protruding bones. Many of them are too feeble for the least exertion, and their minds are scarcely stronger than their bodies. They were indeed a spectacle to inspire, as they did, the keenest sympathy, and to call for every effort of kindness.

Sister Tyler procured a number of photographs of these wretched men, representing them in all their squalor and emaciation. Those were the first that were taken, though the Government afterward caused some to be made which were widely distributed.

Sister Tyler did much good by bringing forward documentation of those atrocities. She had a large number of copies printed in Boston, after her return there, and both in this country and in Europe, which she afterward visited. She often had occasion to bring them forward as unimpeachable witnesses of the truth of her own statements.

Pictures cannot lie, and the sun’s testimony in these brought many a heart shudderingly to a belief that it had before scouted. In Europe, particularly, both in England and upon the Continent, these pictures compelled credence of those tales of the horrors and atrocities of rebel prison pens, which it had long been the fashion to hold as mere sensation stories, and libels upon the chivalrous South.

Whenever referring to her work at Annapolis for the returned prisoners, Sister. Tyler took great pleasure in expressing her appreciation of the valuable and indefatigable services of the late Dr. Vandegrift, Surgeon in charge of the Naval School Hospital. In his efforts to resuscitate the poor victims of starvation and cruelty, he was indefatigable, never sparing himself, but bestowing upon them his unwearied personal attention and sympathy. In this, he was aided by his wife, herself a true Sister of Charity.

Sister Tyler also gave the highest testimony to the services and personal worth of her co-workers, Miss Titcomb, Miss Hall, and others. They gave themselves with earnest zeal to the cause. They provided the men with many healthy recreations, seasons of amusement, and religious instruction.

Exhausted by her labors, and the various calls upon her efforts.

In the spring of 1864, Sister Tyler was obliged to send in her resignation. Her health seemed utterly broken down, and her physicians and friends saw that the cure required an entire change of air, and the scene provided the best hope of her recovery.

For some time, she had been often indisposed, and her illness at last terminated in fever and chills. Though well accustomed during her long residence to the climate of Maryland, she no longer possessed her youthful powers of restoration and reinvigoration. Her physicians advised a sea voyage as essential to her recovery, and a tour to Europe was therefore determined.

She left the Naval School Hospital on the 27th of May 1864 and set sail from New York on the 15th of June.

Sister Tyler spent about 18 months in Europe, traveling over various parts of the Continent, and England, where she remained for four or five months. She returned to her native land in November 1865, to find the desolating war which had raged here at the time of her departure was at an end. Her health had been by this time entirely re-established, and she was happy in the belief that long years of usefulness yet remain to her.

Find the gravesites of the Civil War Clergy by entering their name here: https://www.remembermyjourney.com/Search/Cemetery/325/Map Bill McEvoy can be reached at billmcev@aol.com

Sister Tyler was the epitome of charity and kindness.

You can learn more about Adeline on You Tube — hers is quite a story!

https://youtu.be/L_JyvKDMQuU