The following piece was provided by State Sen. Will Brownsberger, who represents Watertown, Belmont and parts of Boston:

We all now know that the coronavirus is loose in the community and anyone could be unknowingly spreading it. We’ve all seen the terrifying exponential growth curves that project need for hospital beds peaking well above available supply. And we understand that by social distancing, we can bend the disease curve down, lower the peak hospital demand and gain time so that the hospital system has more time to prepare.

What we don’t know is whether we have done as much as we should to check the spread of the virus and what the benefits of additional measures would be. Tomas Pueyo has written one of the more widely read analyses of our current uncertainties: The Hammer and the Dance. His basic argument is that we should be coming down as hard as we can on social distancing initially to buy time (the “hammer”), and that after a few weeks of maximal social distancing, we can let up some while doing widespread testing, contact tracing, and isolation to make sure we don’t reignite community spread (the “dance”).

At the end of his piece though he acknowledges precisely the uncertainty that political leaders are now facing: No one actually knows whether any particular combination of measures will be enough to squelch community transmission.

The rate of transmission depends on a range of hard to measure factors, including the virus, social customs, patterns of economic activity, and on how a society is physically put together. If all of us lived together in one room, we’d all be sick already. If each family had its own island complete with a one year stock of necessities, maybe no one would get sick. The public health challenge is to cut the transmission rate. If the number of persons that each infected person infects is below one, then the number of people sick will start going down.

Early in an epidemic, when spread of a new infectious disease first starts, there is an opportunity to bring the transmission rate below one by aggressively testing, identifying people who are infected, tracing their contacts and isolating everyone who is at risk. This may have been successful in Korea. It’s hard to get direct visibility into the effectiveness of our contact tracing and isolation efforts in Massachusetts, but at this point, it appears likely that the volume of the epidemic has overwhelmed our tracking and isolation efforts.

That is essentially the conclusion reflected in the Governor’s series of social distancing orders: Since community spread has already taken hold and unidentified people are spreading the virus, we have had to go to the next step and try to reduce everyone’s social contacts, not just the contacts of those known to be exposed. To that end, we have radically restricted social and economic activity. We have taken the measures recognized as most difficult in Pueyo’s article, closing many institutions and businesses. I fully support the Governor’s orders, but the question I keep asking myself is: Have we done enough to bring the transmission rate below one and squelch the peak of epidemic? Is our list of essential businesses too long? Could we enforce social distancing more effectively in grocery stores? Only time will tell.

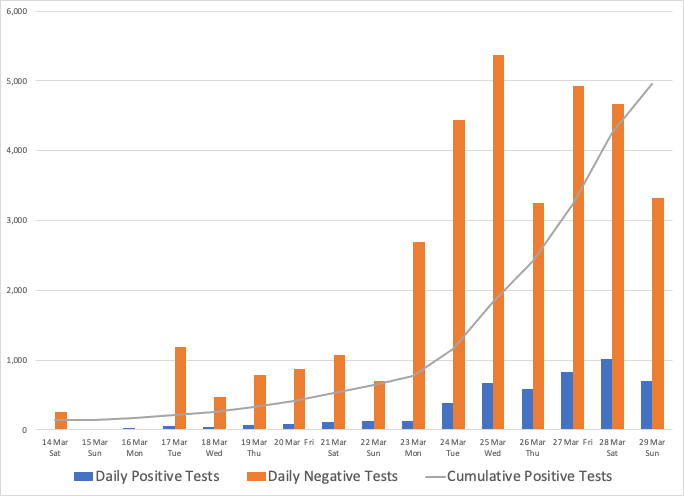

The Governor’s major orders rolled out from March 13 to March 24. There is a 5 or 6 day lag from infection to symptoms and people might not seek immediate testing. Moreover, although the test turnaround is improving, some test results may take days to come back. As of March 30, the full impact of our distancing efforts is only beginning to affect our positive test rates. As we expand availability of testing some reduction of new cases might be masked by our expanded testing.

Massachusetts COVID-19 Tests Results

Source: WB analysis Massachusetts Department of Public Health data compiled by The COVID Tracking Project.

Over the days to come, we will all be watching the numbers anxiously for clear evidence of slower disease spread

Massachusetts’ efforts to control the epidemic sit in a national context. By now, all states have begun to take action. Schools are closed statewide in 47 states and subject to local closures in the other three. Yet the closure of non-essential businesses is not universal. In Mississippi, next to Louisiana where the epidemic is raging, only restaurants are closed. While we don’t have the data to be sure, it appears likely that continued delayed response in other states will lead to persistence of the epidemic as infected people move across state lines. If we had strong federal leadership on the disease, it would help a lot, but since much of the power to protect public health resides with the states, our country may be unable to mount the swift and maximal response that some other countries have achieved.

For now, we know this much:

- Nothing is more critical than ramping up production and distribution of the Personal Protective Equipment that is in short supply for health care personnel and first responders.

- We also have to do a better job protecting those workers still deemed essential, especially those in roles that bring them in contact with many people, like grocery store workers.

- We have to focus on controlling among the most vulnerable populations — our elderly in nursing homes, our homeless, our prisoners — those who may be unable to achieve the social distancing that many of us can.

- We have to roll out relief to the small businesses that our orders have shuttered and to the many who have been working paycheck to paycheck and now no longer have an income.

And we have to keep listening to the data, to the experts, and to each other.

I have a question:

How do the total number of infected people, deaths, and death rates of COVID-19 compare with those of flu and swine flu according to official CDC statistics?