In the early 1990s, Tina Chéry thought she had found her place in the world as a stay-at-home mom and good citizen, as someone who attended church and donated to people in need, even if she felt removed from the problems that affected her Dorchester neighborhood.

The mother of three and her husband had cut back on spending so she could be there when her 15-year-old son Louis Brown came home from school every day. Theirs was the family who welcomed in the neighborhood children, with hotdogs and hamburgers, and lemonade and popsicles in the summer.

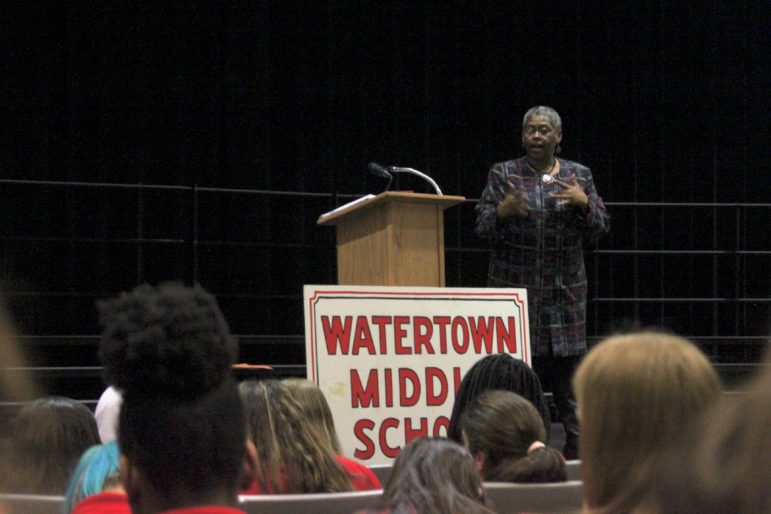

“That was my house. And so I felt that I was doing my part in bringing to life that beloved community. Until Louis was killed,” Chéry told a crowd last Thursday at Watertown Middle School. “Then I realized that I wasn’t doing enough. And so it is through my pain that I found my purpose.”

Five days before Christmas in 1993, Chéry’s son Louis was heading to a holiday gathering for Teens Against Gang Violence when he was killed in the crossfire of a gunfight. The compassionate boy who wanted to stop gun violence had become a victim of it, shattering Chéry’s sense of security and the notion that her stable home could ward off the dangers outside.

“When Louis was killed is when I woke up. I took my blinders off,” Chéry said.

She wanted to move beyond blame and figure out ways to prevent further tragedy.

“We know the research tells us that hurt children hurt others. Hurt children become hurtful adults. So it’s one of the lessons we can learn, so we’re not always reacting when something bad happens.”

Chéry, a chaplain, described her journey from private citizen to peace activist as part of a series of Watertown events this past week to commemorate the life of Dr. Martin Luther King and his message of non-violence. In a time of ongoing street violence and school shootings,

Chéry urged people to move beyond their own concerns and engage with others to prevent further pain and violence.

“I want you to see the Dr. King in each of you,” she said.

Chéry has turned her family’s tragedy into a mission to help others. In 1994, she founded the Louis D. Brown Peace Institute to serve families traumatized by violence and to promote violence prevention programs. She also founded the Mother’s Day Walk for Peace, an annual event in which participants walk from Dorchester to Boston City Hall to promote peace and to raise money for the Peace Institute’s programs.

“Our foundation is peace — peace in the middle, peace in the beginning, and peace at the end, seven days a week, 24 hours a day, 365 days of the year,” Chéry said.

Through the years, Chéry has formed a bond with the Watertown community, which sends buses of its residents to the annual walk, as part of Watertown Walks for Peace.

“Today, I feel like I’m a part of your community,” she said. Before giving her talk, Chéry had spent the whole day in town, visiting with students in the high school and the middle school.

“Being in the high school, there was this sense of hope, a sense of renewed energy, a sense of recommitment, and a sense that I don’t have to work as hard because there’s a new generation really taking their rightful place,” Chéry said.

Though a short ride from Dorchester, Chéry’s trip to Watertown represented a personal journey spanning more than 25 years, and a story of pain and loss channeled into forgiveness.

At the time, the death of Chéry’s son and the resulting investigation generated headlines because his killing didn’t fit into the dismissive narrative often applied to urban violence. Her son was an honors student who dreamed of becoming the country’s first African-American president. The man who was convicted for Brown’s death was the son of a Boston police officer. Chéry then did something that might be unimaginable to some parents in her situation.

“I wanted to know who could raise a child that could kill. So I met his mother and I met his father,” Chéry said. “Woman to woman, mother to mother, heart to heart, I extended my hand of forgiveness, and she accepted.”

Charles Bogues ultimately spent 16 years in prison for his role in the shooting that killed Brown. But before he was released, Chéry wanted a say in his new life, wanted to make sure there was a plan for him. The streets had only gotten meaner, she said, and she didn’t want him to end up hurting someone else or getting killed himself.

“I needed to meet him face to face. And so we did,” she said. She didn’t oppose his parole, but she told him that she had conditions: “If you’re going to come out, you’re going to see me.”

Bogues is out on parole and is doing well, Chéry said. His mother volunteers at the Peace Institute, and he has become involved with Brothers on the Mend, a support group. Chéry’s organization works to help people like Bogues, and to break the cycle of violence for those who are caught up in it. But she expressed frustration at repeated public promises to address gun

violence after the fact.

“Our children are angry, our children are hurt,” Chéry said. “And if we don’t provide that sacred space, where their voices can be heard, where the arts can come out and happen, where everything that they have inside of them can really come out, then we will be spinning our wheels and going in circles, and going nowhere, and continuing to have marches and rallies and picket signs and trying to still deal with Congress. There’s work that we know we all can do and that we are all doing.”

During her talk, Chéry became most animated when speaking to the members of the Watertown Middle School Chorus, who had sung “Sisi Ni Moja (We are One),” as an introduction. One of the middle-school students asked her how long it had taken for her to find the strength to speak publicly about her loss.

“I’m still finding the courage,” Chéry said. “It’s day to day to day to day internal work.”

Several organizations had been involved with bringing Chéry to Watertown, including the Watertown Public Schools, the Kingian Non-violence Coordinating Committee, World in Watertown, the Unity Breakfast Committee, the WHS No Place for Hate Club, the Wayside Youth Coalition, the WMS Undoing Racism Club and the Watertown Community Foundation.

Her visit also came a few days before the town’s 19th Annual Unity Breakfast to honor Martin Luther King’s life. Ruth Henry, a Watertown Middle School Spanish teacher who teaches a Kingian Non-Violence class to students and organizes trainings around town, said that this was the first year that Watertown was holding Martin Luther King assemblies at all of its schools, and the first year they had Chéry there at the schools.

Calling Chéry “one of the most courageous women that I know, humans that I know,” Henry described Chéry as a good friend “who has helped me through many losses and rough times and who has helped many people I know through losses and rough times, and really kind of helped teach me and so many others how to take those losses and that grief and transform it

into change making and commitment and courage.”

The event also featured a song written and performed by Watertown High School freshman Sadie Currier-Brown. Called “Too Young,” the song focuses on the epidemic of gun violence affecting young people, and includes the line “We should not have to fight just to get home alive.” Chéry appeared so moved by the performance that she invited the student to sing at the next Mother’s Day Walk in Boston.

After the talk, Currier-Brown, 15, said hadn’t expected the invitation to sing at the event, but that she would like to do so. She had taken the Kingian Non-Violence class, and was influenced by Martin Luther King’s work, particularly in “how to handle things peacefully rather than by using force.”

The repeated school shootings and the gun debate also affected her as she wrote the song last year.

“I hope people just take the message, that it kind of sticks with them,” Currier-Brown said. “And hopefully, if they’re not involved, that they get a little more involved and try not to stay so quiet.”