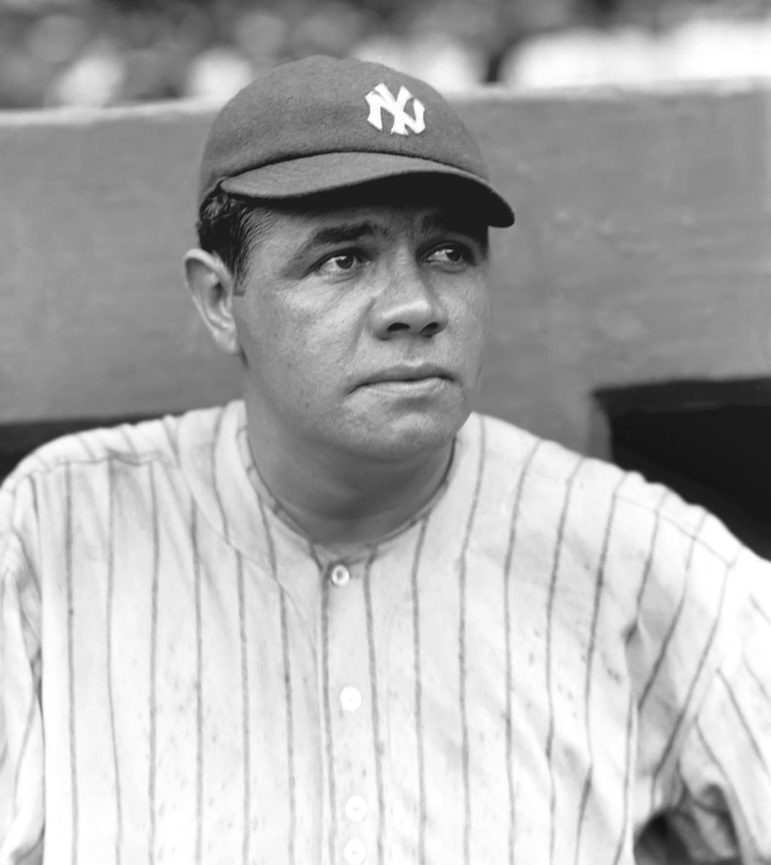

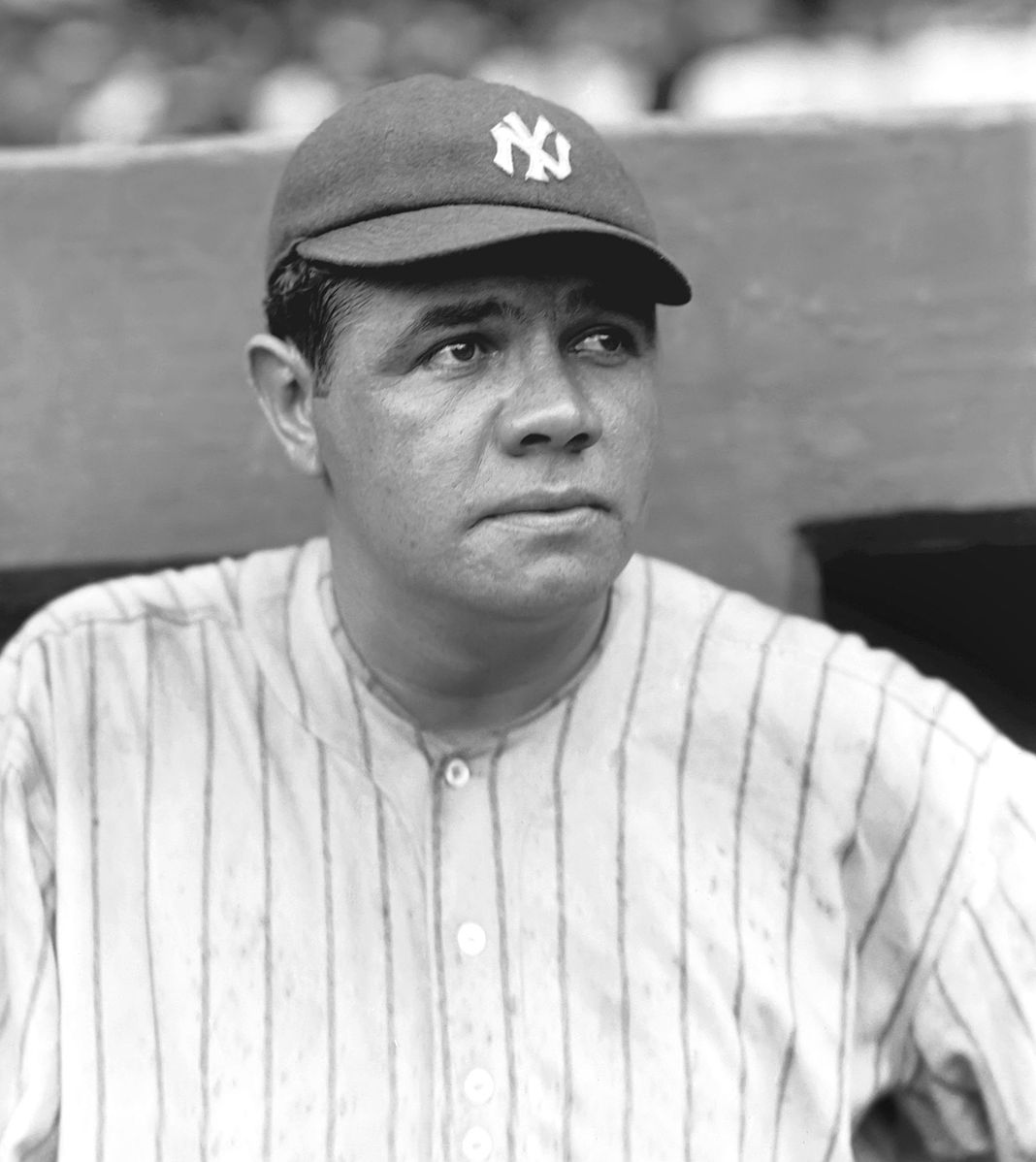

Ninety years ago today (Jan. 11, 2019), a deadly fire claimed the life of the wife of a Watertown dentist. A short time later, the victim’s true identity surfaced, vaulting her death, and the town, into the national spotlight because she was actually the wife of one of the biggest names in sports — then and now — Babe Ruth.

The lede paragraph of a story in the Jan. 17, 1929 issue of the Watertown Sun captured the situation well: “The death of a woman by ‘suffocation and incineration,’ in a fire in the home at 47 Quincy St., was the means through which Watertown was thrown into national and international spotlight … .”

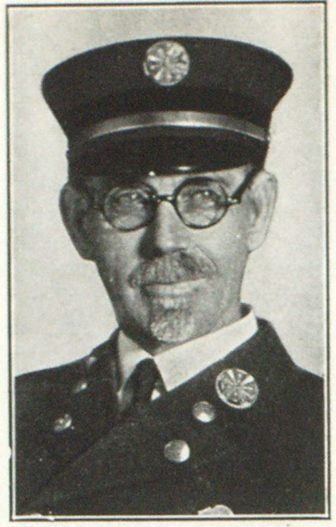

The story’s headline read: LOCAL FIRE CHIEF IS UPHELD IN MRS. “BABE” RUTH DEATH.

The death of Helen Ruth in a fire in Watertown was controversial at the time, and remained in local lore until the house in which she died was torn down in 2004. Before its demise, the house became home to residents whose names are still known around Watertown.

Author Jane Leavy chronicled Helen. Ruth’s death as part of her 2018 book The Big Fella: Babe Ruth and the World He Created, and news stories from the time followed the case instensely.

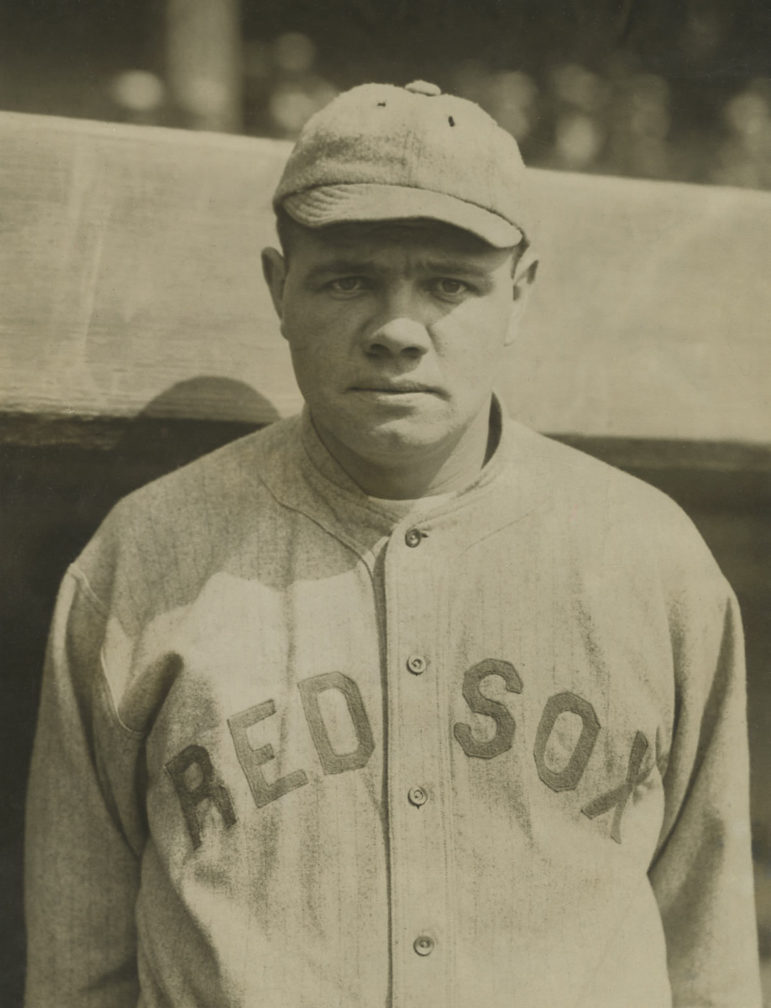

Babe Ruth met Helen Woodford in 1914 when she served him breakfast while she worked as a waitress at Landers’ Coffee Shop in Boston, according to Leavy’s book. They were married in the fall, and Helen would make periodic public appearances with The Babe, but it was noted by the press that she did not make her usual appearance at the World Series in 1928.

Leavy found that Helen had been admitted to the Carney Hospital, then in South Boston, to be treated for a nervous breakdown. When they released her, doctors urged her to go to a Sanatorium in Arlington where “women were treated for hysteria,” Leavy wrote, but instead she went to “the six room cottage at 47 Quincy Street.”

Although Yankee (and former Red Sox) slugger Babe Ruth and Helen maintained publicly that they were still married, neighbors on Quincy Street knew her as Helen R. Kinder, the wife of Dr. Edward Kinder, a Tufts-educated dentist. Kinder told his family that they were married in Montreal, and Helen Kinder’s name appeared on the home’s deed and the mortgage taken out in 1927, according to The Big Fella.

Neighbors reported occasionally seeing a young girl, who turned out to be Helen and Babe’s daughter, Dorothy. However soon after moving in with Kinder, Dorothy was sent to live in a boarding school in Wellesley run by nuns.

The Fire

Leavy described the fire in her book:

“The fire alarm was called in from Fire Box 425 at 10:04 p.m. Captain John J. Kelly of the Watertown Fire Department fought his way up the stairs, crawling on his bands and knees through smoke and flames to find a woman facedown on the bedroom floor. She was in her nightclothes, lying by the door.”

The Watertown Sun reported that Kelly reached her body with the help of Driver James Devaney and Police Officer George Clinton.

Initially, news accounts said that she died at the scene, but the Watertown Police report said she lived for 12 hours afterward, and was brought to a neighbors home at 35 Quincy Street by Watertown Firefighters and Police officers, according to The Big Fella.

At the time of the fire, Edward Kinder was at the Boston Garden for the Friday Night Fights. He was paged at the Garden, headed back to town. When he arrived at the neighbors home, “he collapsed, dropping to the floor with a moan,” Leavy writes.

The initial cause of the fire, made by Watertown Fire Chief John. W. O’Hearn, was “defective wiring and overloading of wires,” according to the Watertown Sun. In The Big Fella, Leavy writes that the fire started in the living room, and was caused by “amateur wiring,” which included spliced wires being attached by tape and no solder. The Sun story reported that “Fuse plugs were found in use up to 30 amps where they should not have been over 10, and when a short circuit occurred these plugs held the resistance, heating the wires and starting a fire … where the source was found in a partition below in the room in which Mrs. Ruth was found.”

The faulty wires, Leavy writes, connected to lights for porches on the first and second floors which had been added by Kinder after he moved in.

The Globe‘s Jan. 17, 1929, story on State Fire Marshal George C. Neal’s report said, “The most plausible theory, the report states, is that of overloading, because several floor lamps and a radio were apparently connected to this receptacle.” Neal’s report, the article said, was based on a report by Albert L. Edson, executive secretary of the State Examiners of Electricians, after he had gone over a report of Ellis L. Dennis, an investigator for the board.

Helen’s Death

Milddlesex Medical Examiner George L. West ruled that the death was by caused by the fire.

The Boston Post story the next day reported the death of the wife of a prominent Watertown dentist, but an anonymous caller told police of Helen’s double identity, and “may have been under the influence of narcotics and the fire in which she died may have been of incendiary origin,” Leavy wrote, noting that the account came from the Hearst-owned Universal Service news agency.

The day of the fire, Babe Ruth was in New York working out at a gym in Manhattan. On Jan. 12, 1929, he received word of Helen’s death while at a party in the Westchester home of his teammate Joe Dugan. He jumped on a train to Boston at 1:15 a.m., according to Leavy’s book.

Reporters tried to reach Babe, and rumors circulated that he and Helen had divorced. Babe Ruth’s manager, Christy Walsh, who was in Portland, Ore., at the time, released a statement saying that the couple was still married, Leavy wrote.

When he finally appeared before reporters, Babe Ruth spoke with “red-rimmed eyes and quivering chin,” according to a Jan. 15, 1929 Boston Globe story. He said “Boys, I’m in a terrible fix. The shock has been a very great one to me. Please let my wife alone. Let her stay dead. That’s all I’ve got to say.”

In her book, Leavy wrote that Babe Ruth had also penned a statement confirming that he and Helen had not been living together for the past three years, and during that time he seldom saw her.

Controversy

Helen’s relatives, who lived in Sudbury, did not accept that their sister’s death had been accidental. A Boston Globe story on Jan. 16, 1929 read:

“Although authorities have expressed themselves as satisfied that there was nothing criminal about the death of Mrs. Ruth, relatives of dead woman have expressed a doubt of the death being accidental. They have declined to accept entirely the official explanation and demanded that the investigation be more thorough. For this reason Dist. Atty. Bushnell ordered the additional autopsy, even though the body has been embalmed.”

Helen’s brother, Thomas Woodford, a former Boston Police officer, said, “What is there to prove the house wasn’t fired? What is there to prove that she wasn’t murdered?” according to Leavy’s account.

Helen’s family maintained that Ruth had asked Helen for a divorce. He had been seen in the company of showgirl Claire Hodgson, Leavy wrote, and she later became his second wife. Helen’s sister Nora told the Universal Service that Helen said she would agree to quietly get divorce in Reno, but she wanted $100,000. At the meeting Ruth told her to go to hell, Nora recalled, according to The Big Fella.

Ruth, however, had been making payments to Helen. Leavy’s book includes a letter from Ruth’s manager, Walsh, to The Babe, in which he references $31,000 that Ruth had given him to pay Helen.

After the fire, Kinder was interviewed by the Watertown Police for four hours, according to Leavy’s book. He admitted that he and Helen had never been married, and also told them that Babe Ruth knew where Helen was staying and that she had originally come to work for Kinder as a housekeeper, two years earlier.

The second autopsy was performed by Suffolk County Medical Examiner George B. McGrath, and he also ruled Helen Ruth’s death was caused by the fire.

District Attorney Bushnell was quoted in a Jan. 17, 1929 Boston Globe article saying: “The case is closed as far as this office is concerned, and, I hope, for the sake of the unfortunate woman who cannot speak for herself, that it is closed as far as anyone is concerned.”

The case was also examined by Waltham District Court Judge Michael J. Connolly, who interviewed Kinder, as well as Watertown police and fire officials. In a March 15, 1929 Globe story, Connolly’s decision was quoted:

“On all of the evidence I find that Helen W. Ruth met death through suffocation and burns between 6:30 and 11 p.m. I find no unlawful act or criminal negligence on the part of anyone contribute to her death.”

Helen Ruth was buried at the Calvary Cemetery in Mattapan. The Woodfords passed down stories of how Helen feared Babe Ruth. The Big Fella has an account of Nora’s daughter, Patricia Grace, who said:

“Aunt Helen was in fear for her life because Babe Ruth wanted a divorce because he was carrying on with women. Of course, we were a Catholic family and she would not divorce. He was trying to get rid of her. He had these hoodlums or what have you. Those are the stories my mother told me.”

In her will, Helen left $29,000 to her daughter, Dorothy, and $5 each to her siblings, as well as to Ruth, according to The Big Fella.

The House

After Kinder, several families lived in the house at 47 Quincy St. According to Watertown resident lists, four families lived at the property from 1939 to 1952. In 1953, the home was purchased by Michael and Bridget Moxley.

The Moxley family owned it until after the turn of the Millennium, and they left their mark on Watertown. Michael started the Shamrock Athletic Club. He and Bridget had five children, two daughters and three sons.

One of the sons, Richard, joined the Marines and was sent to Vietnam. He was killed in action in Quang Nam Providence on Aug. 29, 1968, while serving in L Company of 3rd Battalion of the 7th Marines. He was 21. The park next to Watertown Middle School (formerly the West Junior High School) now bears the name of Private Richard Moxley.

His brother John became a local newspaper columnist, known as “the Voice of the Townies.” His pieces appeared in the Watertown Press, The Watertown Tab, Watertown Sun, the Watertown News Tribune and sometimes Boston’s alternative papers, according to a tribute to him in the Watertown Tab. He died in 2003.

In 2004, the house at 47 Quincy St. was sold to Dallaire-Holt Builders. Len Holt, who was one of buyers, said recently, that the home was a nice one, but was not in great shape. They looked for buyers, but no one was interested.

They decided to tear down the house and turn it into a two-family property. Before they could raze the house, however, they had to appear before the Watertown Historical Commission. There, Holt recalled, the story of Babe Ruth’s wife and the controversy over her death surfaced again. People said that the local lore said that she was murdered, but Holt noted that the death had been declared accidental, due to the fire. The project was allowed to go ahead after a demolition delay, Holt said.

Demolition began at a time when Babe Ruth were once again big topic of discussion.

“It was the Friday before the Boston-New York Yankees playoff in 2004,” Holt said.

The Red Sox were still trying to Reverse the Curse of the Bambino which was said to have started in when the Sox sold Ruth to the Yankees in 1920. The Curse has been cited as the reason the Red Sox lost the 1986 World Series, particularly in game 6 when Bill Buckner missed a ground ball that allowed the New York Mets to score the winning run. The curse surfaced again in 2003 when Boston lost to the Yankees in the American League Championship Series after blowing a lead in Game 7.

Holt recalls getting a call from someone he knew on the street who said he needed to get down to the site.

“There were reporters and cameras from ABC, NBC, CBS, Radio Canada, Radio Australia all out there filming it,” Holt said. “They were saying, look at what Boston is doing to get rid of the curse.”

Holt said he does not know who “dropped a dime” to the media about the house where Ruth’s wife died being torn down.

A fence was erected around the house to prevent people from going on the property, Holt said, and someone hung a banner on the fence saying “Reverse the Curse,” Holt recalled. People were coming and taking pieces of wood as souvenirs.

Before tearing down the house, Holt said he looked around the house. There was no evidence that a fire had occurred there, but he noted, “this was 2004, and a lot of work had been done since.”

The completed two family was sold in 2007.

90 years ago today was January 11th, 1929, right?

Yes. The 2019 was referencing today, not 90 years ago. Sorry for the confusion

Such a cool article.

Editor missed at least three grammatical errors.

Please pass them along, I will fix them. One of the weaknesses of being writer and editor is missing mistakes in your own story.

That’s a very nice article. Must have dedicated a lot of research time. One last peculiar note… The last Moxley, son John, died in 2003, one year to the day before the family house at 47 Quincy Street was torn down. That night in 2004, the Yankees bombed the Red Sox and Curt Schilling aggravated the injury that resulted in the famous bloody sock. Then the Sox miracle occurred and the historic tormentors – the Yankees and Cardinals – fell as the Red Sox won their first World Series in 86 years.

Thanks for the additional note. That is interesting.

The real story on that 2004 house razing on Quincy St. is that it is another example of a single-family house being converted into multi-family because of lax planning oversight in Town Hall and too much leeway for developers.

In the case of that property, which is in a two-family district, the town cannot prevent someone from building a two family, even if it has a single family house on it. The only way it could have been stopped is if it had been declared a historically significant house, and I think even then it would not be guaranteed to be saved.

Great article. I knew John Moxley very well for years and he told me this story. He was as you reported “A true Townee” and wrote many great articles. The Munger brothers and myself assisted John and his dad run the ” Shamrock Road Race ” every year. Good times! Miss it!

Town administrators are now currently making tentative plans to build a temporary park on PFC Richie Moxley Field. Asking Watertown community to voice their concern on behalf of Richie – who gave his life in service of this community and country – to have the temporary high school located elsewhere.

https://www.watertown-ma.gov/Calendar.aspx?EID=22647&month=4&year=2021&day=12&calType=0